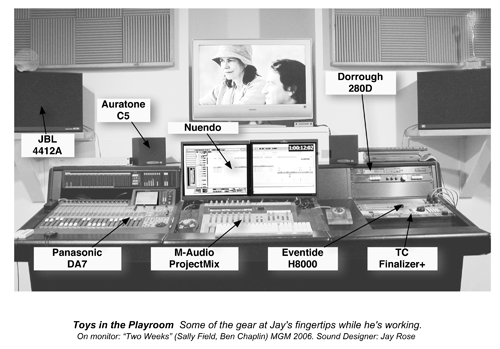

Jay Rose, Digital Playroom, Boston, MA

If there’s a mad scientist of audio and production out there, it may well be Jay Rose. Jay’s specialty is audio production techniques for broadcast and multimedia. He created and programmed the Broadcast Production software for Eventide’s DSP-4000 Ultra-Harmonizer. He is a long-standing member of the design team for Orban’s DSE-7000 and Audicy workstations, was the lead developer for Audicy’s audio-for-video and broadcast effects subsystems, and was its spokesperson at industry conventions for ten years. He has consulted on broadcast product design for Lexicon, and he has run broadcast production seminars for CBS Radio, the US Air Force, and Universal Studios Florida. As a sound designer, his clients include PBS, Buena Vista Television, Turner, CBS, Group W, A&E Network, Discovery Networks, and dozens of radio and TV stations in large and small markets. Corporate audio clients include IBM, Hewlett Packard, Harvard University, and John Hancock. Feature film projects include sound design and editing for “Two Weeks” (Sally Field, Ben Chaplin, Tom Cavanaugh; MGM, December 2006), plus festival-winning local independent films. His “Digital Playroom” includes multiple high-speed DAWs, professional video support, with a generous assortment of high-end effects and an immense music and stock sound library. Jay has won over 150 major broadcast awards as writer, producer, or director, including 13 Clios, and New England Broadcast “Best of Show.” Jay also teaches sound design and editorial techniques at venues such as the DV Expo, Toronto NewMedia Expo, and MacWorld. He is a featured columnist for Digital Video Magazine, and has a couple of books of his own. His most recent one, Audio Postproduction for the DV Filmmaker, while marketed to the DV filmmaker, is packed with a ton of information pertinent to what we do in our studios for radio broadcast. This month’s RAP interview makes a return visit to Jay’s Playroom where we find out what Jay’s been up to since our last visit, and we get a sneak peek at his latest book.

JV: It’s been 11 years since we talked to you. What’s new?

Jay: Well, I’ve actually been semi-retired for the past 20 years, and I’ve managed to be extremely busy during most of it. What have I done recently? Some new software for Eventide, which is shipping in their newest DSP units — a whole bunch of walk-in instant effects, using a lot more power that the new DSP chips have.

They gave their boxes funny names. The Orville was their box starting in the late ’90s, which was much, much more powerful than the old DSP Harmonizers. Now they’re using what they call the H8000. Imagine a rack full of DSP4000 Harmonizers. And you can just go nuts. I’ve got things in there that, for example, take the intonation out of a voice. So if you’ve got somebody who’s actually putting a lot into the read, and his pitch is going up and down and all over the place, it turns him into a car dealer or a robot, but without the robotic sound. It just pulls the emotion out. It’s an emotion drainer. And then I use it the other way, to step up the emotion. So if a person is moving from A to B, I move him from A to C. I’m using A and B and C as range of emotion, rather than musical notes here. So if he’s slightly monotone, like your car dealer, you run him through this, and it almost gives him decent expression, based on what he did. It magnifies his pitch variation.

JV: The Harmonizers back in the day were in a lot of radio stations. Are they still today?

Jay: That’s what they tell me. And they’re in rental catalogs in Hollywood. Guys are renting them for the day to use on dub stages in films. I’m pretty sure they’re still moving them. They’re still sending out PR about my new presets. One of the guys at Eventide told me they’ve been selling a lot of them to the remix guys, to the rap/hip-hop guys, and they’re running music through my presets, which were designed for radio production, things like the Helicopter patch and stuff like that.

JV: What else has kept you busy in the past few years?

Jay: About a year and a half ago, I did a Hollywood feature. It’s coming out on MGM in two months. Biggest thing I’ve ever done of that nature. This was the full sound design, dialogue edit, and music edit for a film starring Sally Field, Ben Chaplin and Tom Cavanagh. This was a dramatic film, actually a comedy/tragedy. I did everything from basic dialogue clean-up, music edits, to supervising the mix. I had to do some surround effects for it, so I took the Eventide eight-channel unit that I have, and I used four channels to generate the surround effect, and four channels as a surround monitor controller. It’s saving me about $2,000 worth of hardware, just on the monitor itself. And when you’re doing surround, first of all, you have to match the speakers, so each speaker was separately equalized. Then you want to be able to control different combinations of them. It was faster for me to just write a couple of lines of code and pop it into Eventide and solder together some switches. But at the same time, what I was doing on the Eventide was creating a voice and airplane background that swirls around the audience — totally disorienting.

JV: It sounds like you’re still having fun.

Jay: It is fun. I’m having a hell of a good time. It was the end of ’87, 19 years ago, that my wife persuaded me to quit the big downtown studio and just do stuff out of the house and only work on the projects that I wanted to. There’ve been a couple of dry periods, but by and large, it’s just been one fun thing after another.

I’m starting a film starring John Malkovich. I just met with the director yesterday. This will be more audio for film. I’m also doing some radio commercials for MGM – writing and producing.

JV: You were doing a lot a radio commercials in the past as I recall.

Jay: I used to be totally radio. I came from a station. I did a lot of midnight station production. I remember doing an all-nighter one Saturday night so that I could listen to this awesome thing that I produced for Sunday morning in the religious “ghetto.” It was a documentary production that they let me run on a Sunday morning, but I was going wild with what I was putting into it.

JV: So you were doing nothing but radio stuff for a long while, then started doing more audio for film.

Jay: Right. What happened is, as the technology made it easier and easier to do sound in sync for film and video, I moved in that direction for a very, very simple reason: the budgets are bigger. I’m given more time to play, and there’s more I can do. It’s still radio sound; I just have to make sure it keeps up with the lips on the screen. But that’s so easy now with the software that we’ve got. Actually, I was the first person in New England to have computer-controlled sound for video — decades ago. My studio was only radio, and this new technology of SMPTE control came out, and I convinced my wife that we should invest in it. It was a lot of money, but suddenly, I was able to actually have the sounds that I wanted to hear in my head happen on the screen. And it’s just gotten better and better since then.

JV: Let’s talk about your books. You’ve got two of them, and I guess you wrote them both in the past ten years or so, right?

Jay: Well, in ’99, I wrote Producing Great Sound for Digital Video. It’s really aimed at people who’ve picked up a $5,000 video camera and are going to go out and either make the world’s best wedding video and try to make a living doing it, or a training film, or shoot their movie. So most of the stuff in Producing Great Sound would probably be already familiar to RAP readers. A good production guy already has these chops. There’s a lot of film-specific stuff and video-specific stuff, particularly about boom mics, getting good sound in and out of a camera, working on lip sync, restoring lip sync -- stuff that radio guys wouldn’t know, but don’t need to know. It was very successful. It’s been the category leader at Amazon since it came out.

So a couple of years after that, in ’03, the publisher asked me for a new edition… which was fine. I said, “Before I write that, I want to write a little book about everything to do with audio post,” which would include all the techniques of editing voice and of editing music — because those techniques are different. You don’t edit music the same way you edit voice. Even the body movements are different.

“I want to write about processing. I want a whole chapter just on time-based processing, starting with a simple flanger and going through an elaborate reverb. I want a whole chapter on just dynamics processing.” They said, “Yeah, yeah. We think we could do well with that book.” So I wrote it. It’s 400 pages. It’s aimed at guys and gals who know a little bit about audio. It’s aimed at people who have some basic audio, or possibly have done a film, and they want to know, “Okay, what’s going on under the hood in all these processors? How can I make them do tricks? What happens under the hood when somebody’s speaking?”

I’ve got a long chapter breaking down voice editing into phonemes. Because once you understand the little phonemes that make up human words, and you realize that everybody produces them the same way, you can start doing tricks, like taking an S off somebody else’s voice and putting it on the one you’re editing, and nobody would notice. But you’ve got to know the rules for that.

So there’s a chapter with a whole bunch of rules about voice editing — when and where you can cut in the middle of a word, or change a word, and why it works. The idea behind the whole book was that you’d read through it, and you might keep it on the shelf as a reference, but you’d learn enough that you can start making up your own tricks. This book, which I wrote for production people, is called Audio Post Production. Because of marketing, we aimed it at the sound for video guys and sound for film, but a lot of people have remarked that it’s useful for radio and music production, too. That ended up becoming a textbook in Russian and German. It got translated. It’s being used in engineering schools. So every now and again, I get a check for the Russian and German versions, which I can’t even read.

Details on both books are at my website, along with a whole lot of interesting stuff for production people, and tutorials, and the famous Orson Wells frozen foods outtakes. If your readers haven’t heard these yet, about 30 years ago, he was in London doing voice-overs for a frozen food campaign. There were four suits in the control room, and they were giving him a horribly hard time. You don’t tell Wells how to read a sentence, and you certainly don’t tell him wrong. He was not suffering fools that day. The engineer was smart enough to roll the tape for the entire session, talkback and Wells’ mic. That tape has been circulating in the underground from one engineer to another. So I put a copy of it up on my website. Nobody knows who really owns it, or at least I don’t. At one point, they gave him such an absurd direction, to stress a word that there’s no reason on earth why you would ever stress that word in a sentence, and he says, in the mic, “You show me how I could possibly stress this word, and I’ll go down on you.”

JV: [Laughter]. Okay! A little treat for our readers!

Jay: And along with that is a piece I did in 1981 with a bunch of actors on what a radio commercial session would be like in the year 2000. I got some really good people in on the session, and that’s become one of the circulating underground tapes, too. That’s all on my website, along with radio and TV that I’ve done.

JV: I’m on your website looking at the table of contents for your book right now and see quite a few chapters that look interesting, like “Hardware for Audio.” What’s your favorite sound card?

Jay: My favorite card, back when I was using cards, was the Digigram. Actually, I still have one on my desktop computer, and all it’s doing is being an output. For the past three or four years, every Mac has come through with S/PDIF audio I/O built in. So if you’ve got a digital studio, you’re there. It’s optical S/PDIF, but a $50 box can turn it into coaxial S/PDIF, or AES/EBU. It’s going right into the motherboard, so it’s absolutely perfect quality, and you don’t mess with the sound card.

For my studio, I’m using a 24-channel I/O that has a card inside the computer, but then there’s a separate rack mount unit that actually has 24 digital I/Os and eight analog. But I have gotten into the habit, since the technology has become possible, of keeping analog audio outside of the tower. You don’t want to put it in there. It’s so noisy in there. Even the expensive cards, they’re only three or four inches away from a switching power supply, and a CPU that is generating square waves up in the megahertz… gigahertz! And so there are harmonics all over the place, just from the computer’s thinking. So if you could get the analog audio into a separate box, it’s going to sound better.

JV: You devote a chapter in the book to “The Studio: Acoustics and Monitoring.”

Jay: Yes, the third chapter of the book talks about the acoustics – both how to do it if you’re building a room from scratch, and how to take an apartment space or a rental space and treat that well, without having to go out and buy a meat locker type isolation booth — how to do it cheaply — and if you’re purpose-building, how to purpose-build. So there’s a whole chapter there on the acoustics and the monitoring, which are the most important aspects of production. If you don’t have good monitoring – which also depends on the acoustics, as well as the speakers you’re using – then you can’t do anything at all, because you don’t know what you’re mixing.

JV: What do you use for monitors?

Jay: I’m using JBL4412a’s, in a nearfield, in a tuned room. When I did this film mix, we were in a THX room, because we were mixing Dolby surround. All of the tracks are things that I had prepared in my studio. When we walked into the THX room, everything sounded exactly the way I expected it to.

I did an IMAX track. You’re familiar with the whole IMAX experience, with 6.1 sound and the six-inch wide film that’s projected on a spherical screen that surrounds you. I did an audio only show to demonstrate the capabilities of the IMAX theatre at the Museum of Science in Boston, and we mixed it there. I did everything at my studio on the JBL monitors, and then one midnight, I went over with a couple of digital recorders and a systems engineer and the director, and I patched into the theatre’s system so that I could do my final mix on their speakers in the room. Everything translated beautifully.

So I am very, very happy with the JBLs. What I like particularly about this series, the 44 series, is that they are so accurate on voice. They give you the whole mix, but they also let you hear everything that’s going on in the voice. Typical music speakers are hyped. They’ve got extra bass, they’ve got extra treble. They sound great on music, but there’s not that much going on accurately in the mid-range. And frequently, there will be a crossover right in the middle of the consonant range of the voice. What it does is, it very subtly distorts the voice/music mix. So if you’re doing a commercial, you may end up making the voice too loud or too soft when it’s played on a good speaker, if you’re listening on music speakers when you do it. So my stuff is always loud, bright, and clear.

JV: Tell us about the rest of your studio.

Jay: For a long, long time, I was using the Orban workstations. Orban stopped development on it in the year 2000. When Orban left Harman International – not Bob, but the company – and became a part of CRL, they decided to concentrate on the transmitter processors, which was what CRL was doing before they bought Orban. They stopped development on the workstations. The Audicy was such a killer when it was new, but in 2000, they stopped writing software for it, and by ’05, when I started working on the Sally Field movie, it was just too old hat. It couldn’t handle a film. So I went looking for other ways to go.

JV: What did you get?

Jay: Well, I’m not going to get into the relative merits of the elephant in the room, but bear in mind, I got a lot of money. The game of radio has been very good to me. I could afford virtually anything that I could name. My wife was saying, “For heaven’s sakes, you’ve been using this Orban system since the DSE. You’ve been editing on this box essentially for 15 years, and just upgrading it. Whatever you buy, you know you’re going to use for another 15 years. If it costs you a hundred grand, spend the hundred grand.” I didn’t spend a hundred grand. I’d rather use that for vacation or something. But I went through everything, and I ended up with Nuendo. I love it. I ran parallel, using Nuendo for the film and the Audicy for my radio and TV projects, for about four months. Then I said the heck with the Audicy. I still have it. I keep it for legacy. But the Audicy controller is in a closet. What used to be the Audicy controller is now a controller for Nuendo. Different hardware, and that space is now owned by Nuendo. If somebody wants to go back into an Audicy project, I can still fire the thing up. It’s probably worth more for me to keep than to try to sell.

JV: Would you recommend Nuendo for radio production? I think Pro Tools and Audition are the two leaders in radio right now.

Jay: Yes. Still, 30 to 40 percent of my stuff is audio only. And I also have both Pro Tools and Audition. When I did the film, I noticed that everybody in LA uses Pro Tools. And you can hire a Pro Tools operator for minimum wage, because of all the schools that teach it. I can tell you a story about that. My son is the assistant chief at a big radio complex in town. He was watching me edit one day and he said, “You know, we have to get this,” and he went to the operations manager and he said, “My dad’s got this Nuendo here, and he can do so much more than our guys are doing in Pro Tools.” And the office manager said, “Yeah, but I can hire a Pro Tools guy fresh out of school, and I don’t have to pay my production people that well” — because there’s so many Pro Tools operators.

Anyway, yeah, I have a Pro Tools rig. I stopped upgrading it a year ago, so mine topped out at Version 6.9. I have Audition, so that I can write about it, and it’s a cool program. But I can do so much stuff so fast in Nuendo.

JV: Nuendo is not cheap, as I recall.

Jay: The software’s $2,500. Then you have to buy the hardware. By the time you finish outfitting a studio, it’s the same cost, essentially, as a full Pro Tools rig. But they have a light version that they call Cubase, just like Pro Tools has their hobbled versions, Pro Tools LE.

I tried them all. I spent a day at the local Apple place with their expert, seeing if I could possibly work in Logic, because I’m a Mac aficionado. And Apple, about six months earlier, had just bought Logic from Emagic. I figured if Apple was going to do for Logic what they did for Final Cut Pro — which is the killer app now for video editing — Logic would be a great program, but they didn’t take it in that direction.

I was saying, “I have to do this and this and this,” and my background was what I could do on the Audicy, and what I knew was possible in programs like Pro Tools and Peak and Deck. And I’m telling the Apple guy, “I want to do this and this and this.” He says, “No, I don’t think we do that.” Well, okay.

Then I sat down with a Nuendo guy, and I ask him, “I hear Pro Tools can use this plug-in, what about Nuendo?” And he’d say, “Oh, yeah. We can use that plug-in, but we’ve got the same functionality built in, so you don’t have to use the plug-in.” It is such a powerful program out of the box, plus it’s compatible. I started using TC Electronics Finalizer. They have a DSP card that fits in your computer that runs your software; it shows up as a plug-in in Pro Tools or Nuendo. I don’t know if it’s compatible with Audition. It might be. So I’m not robbing the CPU. I’ve got multi-band compression on my voice track, multi-band compression on the final mix, and they’re coasting along in this separate DSP card.

Nuendo does things that I know Pro Tools doesn’t, and I don’t think Audition does, but I haven’t kept up with the latest on Audition. For example, you can finish a project – it’s not that relevant for commercials, but say you’ve got a half hour show with some sequences with some real production in them, and a complex mix. And you go through, and you use real faders, and you program your mix moves, and you have filters popping in and out on different lines. You’re ready to mix, and you press a button, and you walk away, and six minutes later, the half hour show is mixed, with all of the processing. So it’s doing all the compression and equalization and reverb generation, and time-critical processes, and it’s doing them faster than real-time.

Another cool thing that Nuendo does – say you’ve got a voiceover, a commercial read, a 60-second radio spot and it’s a little bit long. You take one end of the clip on the screen and you push it to where it should end, and it plays it back, instantly time-compressed. Or you grab both sides of the client’s name and you stretch it out a little bit, and he reads the client’s name just a little bit slower. That’s on the fly. You say, “I want this to end here,” and it ends there. “I want to change the tempo,” and it changes the tempo. “I want to change the key,” and it changes the key. One of the things it does that I don’t think any other software does is this, on each clip, on each region on the screen, not only do you have the ability of drawing a fade – fade-out, fade-in, whatever – or move a fader to actually do a mix type movement, but you can go in with a pencil and change the gain on specific words or syllables, and not by going in and drawing samples. Any program can do that, but it takes forever. On this, you draw a volume envelope, and it isn’t a fader envelope. It’s before any inserts. It’s before any compression. It’s right on that clip. It’s not on the channel. So you can bring up a word, bring down a word, pull out a mouth click, do all that stuff, while you’re zoomed out and listening to the whole thing. It isn’t an automation move. It’s totally separate from anything that you’d do post-processing with the channel fader. It gives you a lot more power, particularly for editing interviews and things like that.

JV: Your book has many interesting chapters: Editing Dialogue, Finding and Editing Music, Working with Sound Effects, to mention a few more.

Jay: The technique for editing dialogue and the technique for editing music are totally different. If you’re zooming in to look at a bump on a screen, you’re doing it wrong for both media, because we don’t listen to squiggles on a screen. On voice, you’re listening for phonemes, in real-time, when you slow down and scrub. There are some 46 – that’s all, 46 phonemes in the English language, that make up every word in everybody’s voice. By and large, everybody creates them with the same tongue movements, the same mouth shape. Once you understand those 46 little building blocks, you can turn any word into any other word, basically. Okay, that’s an exaggeration, but I did a demo in LA and was showing off some techniques last November at a class. I had a piece where my wife’s voice – she was a voice-over actress. My wife passed away a year ago, by the way. She wrote computer books, but she also did a lot of voice-over work. So I had an audio thing that I would play where Carla says, “Have you read Jay’s book?” And my voice comes in, “Actually, I’ve written a couple of books.” I take the S, in real-time, while I’m showing this to people, and I’m using Peak in a laptop – Peak is a great program, by the way, if you need to do voice editing, if you don’t need multiple tracks, but you want to really get in there and edit. So I’ve got Peak rolling in a laptop, and my screen is projected on the wall. I’m showing people what I’m doing. Probably the whole move takes maybe ten seconds, 15 seconds. I took the S in my baritone voice, pasted it onto Carla’s alto, so that she says, in her voice, “Have you read Jay’s books?” You can’t tell that I’m using a male voice to end a female word.

JV: No, I can see how you wouldn’t with the S sound.

Jay: You would with a Z. If it was “Have you seen Jay’s toys” rather than “toy”, the Z has a buzz in it. The book explains why that is, and what the buzz carries. It actually talks about what frequencies those buzzes are at.

JV: What about music editing?

Jay: Music editing is totally different. You have to know how to dance. Or you have to know how to tap your fingers on a steering wheel while the radio’s playing. You have to have that skill. You have to feel the beat.

JV: What am I looking for on the screen, though?

Jay: You close your eyes. It’s about hearing the beat, getting used to tapping your finger on whatever the marking button is in your system. On the Audicy, there was an in and out button that you’d press. On computer programs, you’ve got a key that you press to plant a marker, or to mark, “This is where I want to edit.” You just put your finger on that key, and you tap very lightly in time to the beat, so that your finger’s moving on the beat, and you just press all the way down when you get to a down beat.

JV: Seems like it’d be more accurate to go and zoom in on the wave form.

Jay: What if it’s a pop song? Lyrics are never quite on the bar line. They’re always ahead of it or behind it a little bit. What if there’s no drum, no “beats” to see on the screen? What if it’s a string quartet? Classical, choral, pop music? Here’s what you do if it’s pop, and the singing is not on the beat – because the singing almost never is. Any good pop artist is going to play with that bar line, even though the music’s still moving on the bar line. You mark the bar line, and then slide the edit to pick up the word. If you can make the beats work, nine times out of ten, the music will work in the edit, even if the chords are out of left field. It’s more important to get the beat to work. If the chords are out of left field, you’ll hear it, and you can usually fix that with a cross fade, or perhaps those two chords just don’t belong together, so you take a different bar two bars later.

I was editing a piece, audio only, for a chain of stores called Talbot’s — very high-end women’s clothing. There’s a good 400 stores, plus the catalogs and the website. I was doing a piece for them, and I needed to cut the music down to 60 seconds. It took about five edits to get this three-minute song down to 60 seconds, to fit the way I wanted it to against the voice. I made every edit on the fly, without ever zooming in, just by listening to it, tapping the marking buttons, and then jamming the marks together. Yes, a simple edit, and they all matched. It sounded perfect, even when I’d solo the music.

The book talks about that technique and gives some examples. I included an audio CD with the book, rather than a CD-ROM. Because with an audio CD, you can play it on anything, including your best speakers in the house, and with a CD-ROM, you’re usually limited to the computer speakers. So for the sections on equalization and compression, I wanted people to be able to play the examples with high quality. For the section on music editing, DeWolfe gave me permission to use quite a few cuts from their library to demonstrate the edits.

There are practice exercises in the chapter on music editing, where you’re editing stuff without drums, where you’re editing vocals, where you’re editing a classical piece, where you’re editing a folk song, as well as typical pop and rock sounds. In the chapter on music editing, I also included a diagnostic section, where there are a dozen or so examples of bad music edits that you can hear they’re wrong, but tells you exactly what the mistake is on each one. On this one, the out-point was too early. On this one, the in-point was too early — that kind of thing.

JV: More chapters: Working with Sound Effects, Equalization, Dynamics Control, Time Domain Effects, Time and Pitch Manipulation, Noise Reduction. I think you’ve got just about everything covered here.

Jay: There’s even a chapter called After the Mix, because there’s still things you want to do afterwards. When you think it’s finished; it’s not. The first thing you do – well, obviously, you get it onto the station server, or you dub it, or whatever you’re doing with it. You get it out of house because there’s a deadline. And of course you make sure it’s technically fine – obviously, you’ve got to look at levels, and if you’re going to be compressed for some media, you’ve got to compress it, but I’m not talking about that. Creatively, the two most important things are one, you play the spot or the film track or whatever it is for somebody who’s never heard it, and you watch them, and you watch their face and their eyes and their body language. And the places where they’re listening intently, ahh, you did it right. The places where they break into a smile, you did it right. The places where they’re fidgeting or they’re not quite with you, hey, you’ve got to do better next time. You’ve got to do better with the mix, with the design, with the way you did the edits.

JV: It could have been the copy, right?

Jay: Yeah, it could’ve been. But if you wrote the copy, that’s your baby. And if you didn’t write the copy, you’re still trying to pour what you can into it from your own skill set. That’s the one thing you do. Get somebody who’s never heard it before – and you don’t ask their opinion, you just watch them listen.

The second thing you do is, six months later, you take it off the shelf and listen to it again — completely clear and new. It’s the first time I’ve heard it in six months. What did I do that I liked? What was a happy accident that I can try again next time? What didn’t really work that I fell in love with so much when I was doing it?

There’s actually another aspect of mixing… I’m assuming somebody reading this book, somebody working in our industry, is going to do the editing, and possibly directing the talent, and the sound effects, and the music cuts, and all that, and the mix. In the film business, it’s different. In the film business, you look at the credits crawl by the end of a movie, and there are 400 people who worked on the soundtrack, and a guy’s got a credit for just recording the footsteps. Not making the footsteps, but just recording them. Somebody else edited the footsteps.

It is so specialized in Hollywood. One guy will record dialogue in a studio for ADR, for a dialogue replacement. Another guy in a different studio built a different way will be a specialist in recording the voiceover, which is different from recording voices in a studio. Of course, that’s totally different from recording voices in the field, or on a film set in a studio. They too are specialized.

I’m assuming that you either get a script or you write a script, and minutes or hours later, you have to hand somebody a finished piece. The most important things I could do there, if it’s been an edit-intensive piece -- you’ve really worked hard on building those tracks — take a coffee break, go out to lunch, before you mix. Because if you’ve worked hard making a little montage sequence work, or, gosh, you came up with that perfect music ending where not only did you get the three-minute song down to 59 ½, but it buttons right against the voice in three places, and it always hits the same note on the client’s name, and all those other wonderful music edits, when you start mixing, you’re going to mix the music too loud, because you really like what you did with the music edit. The spot’s about the copy, not about the music — unless it’s a concert spot, and that’s a different thing. So give your ears a break. When I’m working with clients in the room, I will stop the clock and tell them, “Okay, go out to lunch, or at least let me. I’ll stop the clock. You don’t have to pay me for the next 20 minutes. I’m going to sit back and have a cup of coffee.” I don’t smoke. If I smoked, it would’ve been an ideal time to take a cigarette break. So that when you come back and you start moving those faders, you’re listening to the whole spot, and not just the music track or the voice track.

JV: Jay, you’ve got a tremendous amount of information for the people in this book and in your head, and we’ve barely scratched the surface. We won’t wait so long for a return visit. Where can they get your book? Amazon I assume?

Jay: Right. There’s a whole lot about my book on the website, including downloadable samples. And if you click the link on the bottom of the page on my website at Dplay.com, it’ll take you to the best discount sales at Amazon. I’ve got a lot of stuff you can read and download, or just listen to online.