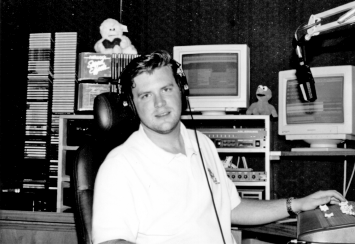

Randy Horvath, Vanilla Gorilla Productions, College Station, Texas

by Jerry Vigil

by Jerry Vigil

We’ve read many interviews and articles about Production Directors who left radio to start their own production company, but can you recall the last time you read about someone leaving radio to start a successful production business when they were barely old enough to buy a beer? Randy Horvath put two and two together very early in his radio career and realized that his talents, as a writer and producer in a small market, were valuable enough to sustain his own production company in this market ranked 232nd in the country. If this is a dream you’ve had for a while, but haven’t quite been able to muster the nerve to take the big leap, hopefully, Randy’s story will give you the fuel you need to put your business plan in order. Randy shows us how this dream isn’t just for the major players in the major markets. It’s for anyone who has some skills, some courage, and a plan.

RAP: Tell us about your background in radio.

Randy: I grew up in Sugarland which is a suburb of Houston, and at sixteen, I started at KACC, a small college station outside of Houston. At that time, our high school was one of three in Texas that had a broadcasting program. I applied for a one day a week on-air position and started out just reading wire news copy. Then you work your way up to an on-air shift. I did that working Christmases, New Years, and all the holidays. I really enjoyed it, and at sixteen, in high school, it was a pretty cool thing to do. I was actually a swimmer from sixth grade on up through my senior year in high school, and I was going to go that route. I was on the United States Swim Team and competed heavily. But by the time I became a senior, the broadcast bug had bitten me. My interest in swimming was waning. I had three scholarship offers, and much to my parents’ dismay, I did not pursue any of them. It’s actually my biggest regret now. I love what I do, but I wish I had taken swimming as far as I could have.

When I graduated from high school, I decided I’d come to College Station, go to school full-time, and see if I could get a radio position part-time. I sent out some tapes which were god-awful. I sent one to KTSR which was an album-oriented rock station, and lo and behold, I got a position doing production. Now, mind you, I didn’t even know how to string up a reel-to-reel. I started on June 1st, 1991, and it was an extremely intimidating situation. I knew nothing about production, yet I was expected to do production. It was simply that the Program Director didn’t want to do it any longer, and being in Bryan/College Station--I think we’re market number two million and two--there isn’t really much of a call for a Production Director per se. But, fortunately, I think I changed that as time went on.

The engineer, who is now a very good friend of mine and still the engineer there, actually is the one who taught me a lot of fundamental skills in production. I think when you’re first starting out, you just do whatever you can. You take a spot that may not call for being off the wall and do it off the wall, and four or five years down the road it really sucks. But at least you took the leap and learned how to put things together. That’s what I did, and I did some really terrible work.

I eventually decided that I wanted to be on-air, and I picked up a couple of weekend and fill-in shifts at the station. Then I got an offer to go to Austin and do weekends and part-time work during the week. That was at KKMJ and KFGI, which now I believe is KAMX. Going to Austin was facilitated partly by Dennis Coleman, whom I’ll get to in just a little while. I spent a very short period of time in Austin, about three months. The reason I left and went back to College Station is probably a story for beer-drinking time. It involved a woman. I decided to come back to College Station, and I got an offer from the same station I was at before. They had acquired a third station, so it was KTSR, WTAW, and the new Aggie 96, KAGG.

Before I left Austin, I got fairly decent in production. So I came back to Bryan/College Station, and I started really getting after production. I decided the on-air thing was not what I wanted to do. I got bored too easily. But playing records four hours a day, I respected. There are a lot of people out there who are very much the entertainer. I’m not that way. I liked production because each thing you did was uniquely different, hopefully.

After being in Bryan/College Station for about three months, I sent a tape to Bill Moffit. He had a position open as a producer. I put the tape in a box with a shoe, and I said, “I just want to get my foot in the door.” I was actually looking for a critique more than anything else. He was the voice of our station at the time. Well, lo and behold, he called me two or three days later and asked if I could come down that evening for an interview. So I went down and interviewed, and he made me an offer.

So with that offer, I came back to the station. The General Manager thought I was nuts because I basically came in and asked him for a raise from about two dollars an hour to ten or twelve. He goes, “You’re out of your @$#%ing mind if you think I’m going to give you a raise.” I looked at him, and I don’t know where this came from, but I just said, “I don’t want to go, but I’ll go.” He gave me the raise, so I stayed.

A lot of people would be going, “Wow, you could work in Houston at Bill Moffit Productions!” Yeah, but I really had a lot of reservations about it. I liked College Station. I grew up in Houston, and there are a lot of people there. It’s hard to get around, and there’s high crime. College Station is nice because it’s only one hundred miles away. If I want to jaunt down to Houston for a weekend, it’s an hour away. So I decided to stay here and just kept producing and producing. I had a few other offers here and there, one in Corpus Christi, and each time I had an offer, I went in to the GM and asked him for a raise, and got the raise.

RAP: You realize you were part of a minority, being able to get raises like that!

Randy: Yeah, and looking back on it now, I was pretty cocky. I walked away when I started Vanilla Gorilla Productions making twenty-eight thousand eight hundred dollars a year as a Production Director, the only Production Director in the market. I think there’s something to be said there, not for me, but for the need for Production Directors in general, and that it is possible to command a decent salary. I don’t think that’s a bad salary for being twenty-two, twenty-three years old in market number 232.

RAP: How many people in the Bryan/College Station market?

Randy: Oh, when the students are here, anywhere between a hundred and fifty to a hundred and sixty thousand. The student population makes up about fifty thousand, so it’s quite a bit. In the summer you lose about half of the students.

RAP: How many stations are in the market?

Randy: When I started, there were probably three or four major contenders. That was in ’91. Now there are maybe nine major contenders. When I first moved here, the cable company ran the Houston stations through the cable, and there were those to contend with. But now, for the most part, the stations here are battling against each other. And it’s become fiercely competitive within the last three or four years. When I first moved here, KLOL out of Houston would show up as a three or four share. Now they show up as a point one or point two. So there’s a significant difference.

RAP: So how did you end up breaking away from radio and opening your own production company?

Randy: When I came back from Austin, we had the three stations, and, boy, we were cruising. We were the only combo group in the market. I had several offers in the course of a year, and I thought, “You know, I don’t have much of a voice. But I feel like I can produce, and everybody wants me to produce. Why can’t I do this on my own?”

So about a year before I decided to split, I started free-lancing more frequently. I would contract out the voice talent to people I had met through the years. Dennis Coleman was one of the men in Austin who put me in touch with other voice talents or disk jockeys who wanted to make a little bit of extra money. And I wanted to test the market to see if there was even a need for it. I wanted to get a feel for what I could charge. Lo and behold, it started to take off, and I decided to move in that direction.

I asked Bill Hicks, one of the owners, if I could use the station’s production facility for my company--use the address, phone lines, that kind of thing--and he said “Sure,” for as long as I needed to. So that was a great boost, and it started to evolve. I started with a couple of clients and that blossomed. It eventually got to the point where I was spending more time on Vanilla Gorilla stuff than on station stuff.

Now, I won’t lie to you; it wasn’t easy cutting the strings. It’s kind of nerve-wracking to start your own business and to take a leap without much of a capital investment, and I did not have much of a capital investment. But I did have a plan. I spent a lot of time doing research, and I had a lot of people on my side helping such as salespeople sending me referrals. But it’s not easy to just walk away, and I don’t think I’ve even entirely cut my strings from radio per se. I mean, I miss it a great deal sometimes, but at the same time, I like what I’m doing.

RAP: When you went out to really pursue the free-lance work, were you already using outside voice talent in your work for the stations?

Randy: Oh, definitely. Ninety to ninety-five percent of everything we did used outside voice talent, and here’s the reason why. As Production Director of a station or stations in a small market--or in any radio market but especially smaller markets--you get the same voices over and over and over again. We had a Program Director who did stellar production, but he was on competing clients. It’s because he’s requested, and the salespeople, I guess, didn’t want to go to the client saying, “No, you can’t have him. He’s already on this spot or that spot,” even though it was in the better interest of the client. So there was very little separation.

You had and still have very talented people in markets this size who do an exceptional job. But at the same time, you have some disk jockeys who may or may not like to do production. They don’t put their heart into it, or they’re busy that day, whatever it may be. And that’s where I think I found the need. There are a lot of clients in markets this size that have a budget. They don’t mind spending money. They just want something that is going to sound good. And, at the same time, they can’t walk into Houston or Dallas and pay union talent rates, pay studio time at one hundred and fifty dollars an hour, and pay needle drop fees. So what we try to do is kind of be the in-between and provide them with a professional product without breaking their budget, something that will help them achieve their goal by having a commercial that is going to stand out amongst everything else.

RAP: How did you go and get these clients while you were still at the station?

Randy: In the beginning, a great deal of it was referral, or meeting with a salesperson who was stumped on writing a spot. I went to the salespeople and said, “Look, this is what I’m trying to do. Do you have anybody who might be interested?” You slap together a tape, they take it to the client, and the next thing you know, YOU have a client. I wish I could tell you it was an exact science, that I methodically planned it out, but I didn’t. I just kind of did it, kind of like I would venture to guess that most Production Directors that begin to free-lance do. I think that without that network of sales folk who were at the stations, I wouldn’t be where I’m at today because their referrals carried a lot of weight. And as long as the clients were spending money on the station....

At the same time you’ve got to remember, if I’m a salesperson, and I know of a tool that is going to help my client succeed, and I show them what that tool is and how to use that tool, and it works for them, that client’s going to come back and spend more money. It took a load off the sales rep’s mind because this is a market size where the sales rep not only has to service the client, but write copy and follow the production through. So, this kind of took a burden off their back. Plus, it made their client happy and made me a little bit of money.

RAP: So when did you actually make the break and start out on your own?

Randy: I fully took the leap in January of 1996.

RAP: How did you finance a new studio?

Randy: We took out a loan for the equipment and set up a studio.

RAP: You say “we.” Is there a partner?

Randy: Dennis Coleman was originally a partner of mine. We filed as a subchapter S corporation for tax reasons, and Dennis’ father gave us a start-up loan. Our ultimate goal was to eventually either move myself to Austin or have Dennis move here. I don’t have the full story, but he went to Mexico for a while. In the same week that Dennis left, Casey, one of the voice talents I was using who was based here locally, and her husband bought out Dennis and his father’s shares in the corporation, and they helped secure the loan through the bank. Jim was an established businessman here, and that’s what gave us the step forward.

RAP: Did you set up in some office space somewhere?

Randy: I moved into a studio that is actually five floors below the radio stations I worked at.

RAP: What did you equip the studio with?

Randy: I have a Tascam M2516 board, SAWplus, and the Editor Plus. We use the CardD which is on a PC with a 2-gig drive, 34 megs of RAM, and various other items, I’m sure. I’m not a tech head. There’s a Yamaha SPX990, dbx 286 mic processors, Technics CD players, a Sony DAT, and a Technics cassette deck. I have two Tascam reel-to-reels, and those are essentially for dubs. There’s an AKG C414 microphone, an SM7, and Allison monitors.

RAP: What are your likes and dislikes about the SAWplus?

Randy: We got to test drive a copy of SAW and SAW really bit. SAWplus has just been the difference between night and day. I love SAWplus. When I was at the station, we used The Editor, so going to SAWplus was heaven. I’ve watched ProTools in action, and I like ProTools as well.

RAP: If you had to build that studio today, how much would it cost?

Randy: Fifteen or sixteen thousand. One of the good things I did was I started acquiring equipment while I was at the station. I didn’t take any money out of what I was making. I lived off my salary from the stations, and any extra cash I had, I used to acquire equipment. I bought the board before I even had a studio. It sat in a box for a year before I used it. I bought little pieces here and there, so when I jumped out in January, the money wasn’t all going toward equipment. A lot of it went to fund my salary.

If you think you’re just going to jump out and start a business and make enough to match what you were making before, I think you’re living in a dream world. That will eventually happen, and hopefully it will surpass that. But to start out, there’s going to be a period of time where you have to fund yourself just for cash flow reasons. I would say about half the money we took for the loan went for that, and half went for finishing out the equipment and purchasing the libraries that we needed.

RAP: What are you using for production music?

Randy: NJJ, Not Just Jingles. It’s distributed by Killer Tracks. It’s a very contemporary sounding library. And we also use Network, and a long time ago I purchased a Production Garden buy out library. And there are a few pieces of buy out music here and there.

RAP: Are you producing promos and IDs as well as commercials?

Randy: It’s about fifty fifty. We do about fifty percent radio station services and about fifty percent commercial production, from a revenue standpoint.

RAP: What are you doing to get the radio station business?

Randy: We’re getting it by referrals from the stations that we’ve gathered in.

RAP: Word of mouth. It sounds like you’re a big fan of it.

Randy: It’s the only way. It can boost your business beyond your wildest dreams, or it can kill your business in a heart beat. It’s a gamble. But if you do a good product and you really service your stations just like you would a client, then there’s always going to be good word of mouth. I’ve been hesitant to put an ad in the different trade magazines. It’s not because I don’t think we would do a great job. It’s just that if you take on too much at one time, I don’t think you get to service them as adequately as you should. I’m real careful about that. When I walk into a client that I deal with direct, I promise them that for every penny they spend, they’ll get a penny back in production. I think the same thing has to be done with the radio stations. They’re no different than any other consumer. They’ve got businesses to run, and the imaging is a very key part to any radio station.

RAP: We’ve heard it too many times that a great spot really starts with the script. What is your approach to writing a creative commercial?

Randy: It’s another one of those non-methodical type things. I don’t know how the other markets are, just from lack of experience of working in those markets, but I find that in this market there’s a tremendous education process that has to go on with the client. I think it’s from a lack of training from a sales standpoint. A lot of clients either don’t take the time, or they don’t have the fundamental understanding of how marketing works. And it’s really not rocket science once you start putting theories together. When I sit down with a client, the first thing I do is identify their needs. What are their goals for their business? What do they want to see change? I think by establishing a business-type relationship--not a vendor-client relationship--it becomes more of, “Hey, I’m your business partner here.” You get a better fundamental understanding of how their operation works, and you can create a better product. What that translates into with copywriting is like plug and play. Yes, you have to come up with an idea; you have to develop the creative. But once you have the elements that you know you need to focus on based upon their needs and where they want to go, I really feel that at that point you just start filling in the blanks.

RAP: What kinds of turnaround times do you provide?

Randy: Well, that’s like saying, “Do you want a customized Porsche or do you want one you can drive off the lot?” It varies from client to client, and from project to project. Now with stations, we usually promise anywhere from forty-eight to seventy-two hours, sometimes twenty-four depending on how bad of an emergency it is. If they’re just really in a pinch, we’ll swing up to play with them, and DCI has been a wonderful godsend in that area. But with direct clients, it really can vary, and it really depends on their needs. If they have to have something start right away, we can get it done same day. But if we have time to spend with it, I’d say we usually get it out in seventy-two hours or maybe another day past that.

RAP: Your business is very young, and you probably learned some very basic but very important things right off the bat. What comes to mind, and what would you do differently?

Randy: I think that if I had to do it all over again, instead of pursuing a Journalism degree, I would pursue a Business or Marketing degree because it makes your life a lot easier, understanding cash flow, understanding the importance of revenue as well as watching over expenditures. Your product is first and foremost your most important aspect. But I don’t care if you’re selling shoes or if you’re digging ditches, if you don’t price your services or your product appropriately, and you don’t watch how much it costs you to operate and how much those margins are, it doesn’t matter if you have the best commercials in the world and won every Marconi or Clio award there is. You’re not going to be in business two years from now. It won’t happen.

I think there has to be an even balance between the two. I think you have to have a fundamental understanding of business, and at the same time you have to have that producer’s ear. I guess the trick is finding if you have one or the other, then team up with someone who can complement it. Bob Oakman will admit to you in a minute that he’s not a businessman, but he’s an excellent producer and voice talent. That’s why he’s teamed up with us--as far as his free-lance is concerned--so that he can have someone ride herd and make sure he’s getting the rate he should be getting for what he does. I think with those types of relationships, you’re only going to succeed.

RAP: Are you doing anything else to grow your business, or is it all word of mouth right now?

Randy: I send out a lot of demo tapes and do a lot of cold calls. I think we’re at a stage now where we could have more radio stations on board, and I definitely think we’re up for that challenge. When I say “we” I’m talking about the voice talents and myself. From a commercial standpoint, I think the same way. The last year was more of a learning experience, a chance to get my feet wet, feel the water. There’s no hurry. I’m twenty-four years old. If I can make a living the first and second year, then I think the third and fourth year, if we have a good product and keep growing it and adding better voice talents, it’s just going to keep going.

RAP: You mentioned leaving a pretty good salary as Production Director of the stations a couple of years ago. Are you making more now?

Randy: I am now. Last year I wasn’t. Last year I think I took out gross twenty-one thousand. That’s not a lot to live on.

RAP: Is there competition for you in your market?

Randy: Well, if I tell you no, I don’t want anybody moving down here. But, no, there isn’t. Well, there are a couple of guys that call themselves a production company, and it’s not a slam against them, but they’re a perfect example that you can have the best toys in the world and not know how to use them.

RAP: You’ve had success in the year and a half you’ve been in business, and it sounds like you’re headed in the right direction. What one thing would you single out as most contributing to your success so far?

Randy: I would say the wonderful voice talent we have. They’re wonderful, and they’re willing to work for peanuts. It’s not that bad, but we don’t promise we’re going to make them rich. We just promise we can send it to them consistently. So over the course of the year, they make a pretty good income. But without the voice talent, we couldn’t do it. Dennis goes up to bat for us on a daily basis. If we’re in a pinch, he’ll find me the voice talent in Austin, and that helps. Bob is the same way. And I’ve just named these two, but there’s a whole roster of voice talents that do the same thing for us on a day-to-day basis.

RAP: About how many people are in your talent bank?

Randy: People we use on a day-to-day basis, I would say anywhere from eighteen to twenty-two. But we’ll find you any voice talent. If you want to use Patrick Stewart, we’ll go track the agent down and negotiate the deal if you have the budget for it. Most of these talents are around the state, but we have a few that are out of state. We have a few in Houston and a couple in Dallas, and we’re always looking for new voice talent, somebody who is willing to get a little bit of exposure or wanting to work their way into the biz. I mean, we do like people with experience--don’t get me wrong--but we’re looking for somebody who is not going to charge us two thousand dollars for a page.

RAP: What are the big differences between working at the station and working at your own studio for yourself?

Randy: I work harder now. Before I was married, I was working about twenty hours a day. This was with Vanilla Gorilla last year. Of course, that varied. Now that I’m married, I’ve cut it back, or I wouldn’t be married. I would say now I work twelve to fourteen hours. I’m a workaholic, but I’ve realized I’ve got to cut back. There are certain things you can and can’t get done during a day. It has become a matter of time management and working off a schedule. When I get here in the morning, the first thing I do is open my laptop. I’m on Schedule Plus, and I’ve got my day planned. I don’t always stick to it, but at least I’ve got things organized, and I know what I’ve got to get done.

RAP: How do you handle engineering problems with the studio?

Randy: That friend I told you about way back at the beginning, he comes down and he helps me. He taught me a lot about engineering. I won’t say I know a great deal, but he’s attempted to show me a great deal. There are little maintenance things that I can keep a handle on, but if we have a major catastrophe, Mark’s only a page away.

RAP: Are you utilizing the Internet in any way?

Randy: I’ve got an e-mail address which is

RAP: Has being out on your own opened up any opportunities that might not have come along had you stayed in radio?

Randy: I’ve actually had the opportunity to work in television as far as creating television spots, and that’s something I would have never got to do if I were still at the radio station. We have a real close relationship with a film production company that’s based here, and we do all of their audio post. That’s a whole different world, and I think it’s helped me diversify.

RAP: Would you consider going back to radio as a Production Director?

Randy: I take a lot of pride in what I’m doing now, and there have been plenty of times in the last year and a half when I’ve thought, “Did I make a mistake?” especially in one of those months when the cash flow wasn’t exactly right. I don’t know. I think I would have a hard time trading it all back in. I miss it--don’t get me wrong--but there are parts of me that don’t miss it. I haven’t been in the larger markets, so I don’t know how the interaction is with salespeople. Even though I had some good ones who were on my side, there were some run-ins, too. Those situations where there’s not a lot of professional courtesy for the Production Director...boy, they’re hard to swallow. I think that would keep me away from going back.

RAP: So dealing with salespeople is the thing you miss the least?

Randy: Definitely. It just seems like the Production Director is the one guy who gets beat around like a basketball, and that part I think I still resent. But there were some good times, too. If Vanilla Gorilla did not work out for some reason, if there was a family tragedy and I had to move, I would probably go into production, not on my own, but probably for a production house. But I still have a love for radio. I actually enjoy listening to radio more, now that I’m not part of it every day.

RAP: What advice would you give to someone who wants to leave radio and start a production company like yours?

Randy: The first thing you do is develop a business plan and have a good one. Be realistic. There are a lot of programs out there that you can get, whether it’s shareware or at the book store, that can help you develop a business plan. Ask questions about the market you’re looking at opening up in because that’s where the core of your business is going to come from, unless you’re in the radio station liner business. You’ve got to ask questions specific to that target demographic.

It amazes me, the number of production companies that start and fail. The reason I say that is because we’re the people who walk into a business and ask clients, “Who you are targeting to? How are you going to reach them? How are you going to do this and do that?” Yet, when we start our own businesses, we never seem to ask those questions. If you sit down and develop a business plan and take your time doing your research and being realistic about it, everything else will start falling into place. And it’s going to tell you, “Well, this market is not going to work for you,” or, “This market has potential, but it’s going to require this amount of work.” Nothing is an exact science, but it gives you a guideline.

Secondly, get a great accountant, not just an accountant, but a great accountant because it will make all the difference in the world, and I don’t mean from a tax standpoint. Yes, that’s important, but you need somebody who is essentially going to be a partner with you, somebody who is going to question every dime you spend. “Why are you spending it here? Why don’t you spend it there?” It’s important. It’s not like somebody riding herd over you; it’s somebody who is going to help you succeed. I learned that the hard way, and I spent my first year with a horrible accountant. I’ve corrected that mistake. What’s more, that same accountant has become a great client. It’s been a good relationship, and the company’s been more profitable.

RAP: Where did you get the name Vanilla Gorilla?

Randy: Oh, that would have to be another discussion over a beer. I’ll give you the sound good version. When I was trying to develop a name, I wanted something that would stand out. It wasn’t going to be “Joe Blow’s House of Hot Spots” or whatever. When you heard it, whether you knew what we did or not, I wanted you to remember the name. I think that’s the single most asked question we get on a day-to-day basis. “Great name! Where did you come up with it?” And it was between that and “Sizzly Grizzly Productions.” I like monkeys better.

We’re in a business where we have to show people we’re creative, and when you’re dealing with ad agencies and radio stations, you’re dealing with the same consumers you’re trying to target when you’re creating a spot for a stereo store. You have to get into their mind and slash away the clutter like anybody else, and I think that’s what I was trying to do. I want you to walk away and remember the name. We’ve had people think we sell ice cream. We’ve had people think we have something to do with parties, like dressing up in gorilla suits. It’s been fun, but more importantly, I can’t tell you how many times, when I’m introduced to someone I’ve never met before, they’ll introduce me and say, “This is Vanilla Gorilla.” The other person will say they’ve seen our sign or, that they’ve heard this or that or whatever, and that’s a good feeling.

♦