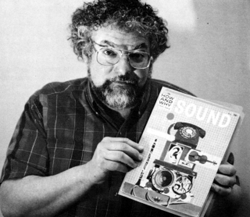

Jay Rose, Proprietor, Digital Playroom, Boston, Massachusetts

Jay Rose started like many of us do, in high school, with dreams of becoming a disk jockey. But rather than spending several years on the air and in production at a radio station, Jay took the solo route much sooner. A 4-track studio in his home quickly became a multi-studio production facility in downtown Boston and his career took off. Eventually, Jay ended up back in his house once again. Only this time, his meager 4-track home studio has become his Digital Playroom, complete with an Orban DSE-7000, an ISDN line hooked up to a Telos Zephyr, a couple of Eventide DSP4000 Ultra-Harmonizers, a Marantz CD recorder, a couple of synthesizers, a PowerMac with a ton of audio software, a couple of DAT decks, and an impressive array of effects and other toys. Jay's list of clients is just as impressive. The Clio/Emmy award winning producer stays busy with clients such as the A&E Network, CBS Television, PBS Television, AT&T, Blue Cross/Blue Shield, Aldus Corporation, AKG Acoustics, Abbott Laboratories, and dozens of TV and radio stations around the country and in Canada just to mention a few. And Jay's talents go well beyond production. If you use a DSE-7000, you've probably enjoyed the "user-friendly" manual that goes with it. Jay wrote it. As you'll discover, Jay's technical expertise is well above that of the average producer, and we didn't hesitate to take advantage of that. Join us as we pick his brain on the latest ISDN technology and get some tips on home studios, directing talent, and more.

Jay Rose started like many of us do, in high school, with dreams of becoming a disk jockey. But rather than spending several years on the air and in production at a radio station, Jay took the solo route much sooner. A 4-track studio in his home quickly became a multi-studio production facility in downtown Boston and his career took off. Eventually, Jay ended up back in his house once again. Only this time, his meager 4-track home studio has become his Digital Playroom, complete with an Orban DSE-7000, an ISDN line hooked up to a Telos Zephyr, a couple of Eventide DSP4000 Ultra-Harmonizers, a Marantz CD recorder, a couple of synthesizers, a PowerMac with a ton of audio software, a couple of DAT decks, and an impressive array of effects and other toys. Jay's list of clients is just as impressive. The Clio/Emmy award winning producer stays busy with clients such as the A&E Network, CBS Television, PBS Television, AT&T, Blue Cross/Blue Shield, Aldus Corporation, AKG Acoustics, Abbott Laboratories, and dozens of TV and radio stations around the country and in Canada just to mention a few. And Jay's talents go well beyond production. If you use a DSE-7000, you've probably enjoyed the "user-friendly" manual that goes with it. Jay wrote it. As you'll discover, Jay's technical expertise is well above that of the average producer, and we didn't hesitate to take advantage of that. Join us as we pick his brain on the latest ISDN technology and get some tips on home studios, directing talent, and more.

RAP: Where did your career in radio production begin and how did you wind up working out of your own studio at home?

Jay: In high school, I knew I was going to be a disk jockey, with the absolute certainty and total wrongness that a high school student will have. I was doing everything I could possibly get my hands on with PA systems, doing announcements in the school, etc.. I even built a pirate radio station. When one of the local AM stations would sign off in the New York City area, I would sign on two minutes later with a ten watt transmitter that I built myself using tubes from an old power amplifier and an RF generator. I modulated it with a PA system amplifier. I would put on a tape and walk around the neighborhood listening to myself.

After high school I went to Emerson and discovered a couple of things. I discovered the world of production, which is good when you've got pipes like mine, because I found out I was never going to make it as an air talent. The year I graduated from Emerson was the last year they required eighteen credit hours of speech theory, argumentation, phonetic transcription--things I had no desire to learn whatsoever. The whole freshman class was struggling through this stuff, and it's the basis for what I do every day now.

So I graduated from Emerson having been Chief Engineer of the AM station there and Program Director of the FM station, and it was the time of 'Nam. One of my instructors encouraged me to write rather than just to make noises, to try to do something creative with the medium. Some of the stuff I had written won a minor prize. So my name was on a mailing list, and I got a call from Bowling Green State University in Ohio saying, "We see you won this prize. How would you like to come out here and take a graduate course and get an assistantship so you won't have to pay for your graduate degree." I said, "You mean I don't have to go to jail or to Canada or to 'Nam?" And they said, "Sure." So I went out to Ohio where I was the Program Director of the noncommercial FM station and, at the same time, worked on their TV station. I could do anything I wanted to with the broadcast day. So I tried a lot of experimentation with things like program wheels and pre-formatted elements and stuff that NPR suddenly discovered fifteen years later. I had no idea what I was doing, but I was having a lot of fun.

I came back to Boston after I finished at Bowling Green and was offered a job at a down and out film studio where I got plugged into the advertising world. The film studio needed somebody to rewire the sound system. So I started rewiring, and the guy saw that I knew something about technology and would work cheap. So he made me Production Director of a film company. I'd had two film courses. With that kind of management, it's not surprising that a year later they went belly up. In the course of that, I created a classic film. I did a midnight ninety-second TV spot. I wrote and produced it for the Lifetime Hair Trimmer Comb. This was a spot that ran PI on marginal UHF stations. You run this little plastic thing through your hair, and you'll never need to go to a barber. So the film studio went bust, and I looked at my reel and said, "Gee, I'd better stay out of the film business, but, boy, there are some nice sound tracks here." So I started doing work for ad agencies. I was doing sound, primarily radio and some sound for TV, basically out of my house. I was doing editing, sound effects work, editing library elements, the kinds of things you do in a production room. I found that I was able to do it in my house instead of at a station and make a decent living at it. So I just kept doing that and eventually had a big downtown studio with four rooms and twelve employees, and we were doing about sixty percent of anything national to come out of the Boston area--strictly advertising, no music recording.

I sold the studio in an urban development move. There's a skyscraper there now. Then I went to work at a mega-facility which then became Editel. At the time, it was Century III Boston. I went to work as their chief sound designer doing what I'd been doing all along, only now I was doing it for NBC and Parker Brothers and outfits like that. I was spending most of my time with ad agency types working under a lot of pressure. When you do sound in a big facility that does 35 millimeter film and network level video editing, even though you have a beautiful room to work in and you're paid very well, you're dirt because the sound guy is the guy who gets the last piece of it after the budget is burned, after the video edits took three days longer than they were supposed to. I found myself doing a lot of Friday afternoon sessions that started at nine a.m. on Saturday, sessions where there was no money to bring in any help, and, of course, it had to be on the air on Monday. After about four years of that, my wife told me to quit before I drove her crazy, so I did.

I built a studio in my attic. I essentially came full circle from where I'd started only I'd started with a Teac 3340, and this time I had a TASCAM 8-track. That was about eight years ago. The studio flourished. One of the first major things I got into was the Orban editing system. The room has since grown from my attic to a first floor room because I needed to be able to stand up without bumping my head. Along the way I discovered that when you're working for yourself, you can work on almost anything you want to. If a project is interesting, you don't have to say, "Gee, is this what I'm in business to do?" So if I'm spending a day working on programming for Eventide, or writing an article, or writing a script for somebody, and my studio isn't in use, there's very little overhead. I don't have downtown real estate. I don't have downtown employees. There's an amazing amount of freedom.

RAP: Outside of audio production work, what else are you doing?

Jay: I've got the opportunity to do some software work for Eventide. I'm doing a bunch of writing and a couple of books. My wife writes computer books, and we've written three of them together. I wrote the manual for the Orban DSE-7000 and some manuals for people as weird as Mackie Designs. They're nuts, but they saw some of what I'd written for Orban and they said, "He's nuts, too," and they needed a free-lancer to fill in. I think a lot of my stuff ended up in the 1202 manual and in some of their promotional material. If you go to the Eventide Home Page, you can grab the manual I wrote for the new Ultra Harmonizer. They put the whole thing up on the Web page. I did the stuff that wasn't straight enough for Mackie, stuff that I'd been dying to do, including a couple of approaches that Mackie had rejected as being not really serious enough for an equipment manual. It's all down to earth technology, and all about trying to tell somebody a good way to run a piece of equipment. But at the same time, there's no reason you can't write a high-tech manual that sounds like a human being, that sounds like you enjoy working with the stuff.

RAP: Where does most of your revenue come from? Is it from the writing or production?

Jay: Producing commercials, most of it broadcast promos. I don't know why, but in this present economy for the past couple of years, the only people who are really spending money trying to do interesting advertising are the car dealers and the broadcasters. On the local level there are a lot of fairly decent TV campaigns for radio stations. I don't know if you're enough into promotion that you've heard of a company called Custom Productions. Among other things, they created a very famous TV spot for a radio station called Open Radio where a guy opens up a radio and starts pulling out the things he doesn't like and starts putting in the things he does like. I do the sound for some of their original spots and all of their syndicated spots. So those are my tracks, my mixes, and we're promoting radio stations pretty much all around the country.

RAP: So television audio for radio station campaigns is one large area for you.

Jay: A large area. The other that I do is a lot of radio spots for TV stations, for the network broadcasters and also for a lot of local stations around the country. I do radio for WGN in Chicago, for KTTV in LA, for WPIX in New York, for Channel 4 in Miami, and of course, for the Group W outlet up here in Boston, WBZ.

RAP: You wrote about ninety programs for Eventide's new DSP4000 Ultra Harmonizer. I was able to check some of them out at a recent NAB show and was blown away. I can write some basic programs on a number of effects boxes, but the programs you wrote aren't just simple little reverb programs or delay programs. There are some incredibly unique programs on the DSP4000. Is it as easy to program the DSP4000 as it is to program any effects box?

Jay: I'd say it's easier. I had poked around on the H3000 and got into the programming on that, and that box is sort of a horror show to program. You've got to keep a mental picture of all these different generators and processors and then, one by one, wire them up. Then I got the 4000. I saw it at a show and it looked like it would do some neat things for me. So, I bought it. I opened up the manual and, lo and behold, it comes with a high level programming language built in. You can sit at your PC, or my MAC, and actually write a program that says things like, "Take a filter. Give the filter this curve." And you describe the curve in terms of poles and things like that. You just describe this stuff in text. "At a certain turnover frequency, take the signal coming in the input jack, send it to this filter, take the low frequencies from this filter, invert them, and send them to this pitch shifter. Put a knob on the front panel. Take the knob, multiply it by minus one, look at the incoming level, combine that with the knob, and use it to modulate the pitch." You're just describing all this in text. Then you download it to the Ultra Harmonizer then press a button and listen to it. This is a very high level language. If you can work Basic, if you understand Basic, then it's real easy to start programming.

RAP: Describe one of your favorite programs you wrote for the DSP4000.

Jay: I have a patch called "Public Address" which actually generates the realistic feedback of a high school auditorium or a press conference or anything like that. It picks out a frequency, which you can choose, but when it accumulates enough frequency in the input, it starts to grow and you get the whistle. It sounds exactly like feedback, and when you stop talking, it slowly decays, just like feedback. To make it complete, I put in a "Tap Mike" button on it. You hit a button on the front panel of the Ultra Harmonizer, and you get that characteristic sound of somebody thumping along on an old dynamic mike in a big auditorium.

RAP: When did you start getting serious about writing effect programs?

Jay: The first one that I started playing with was a de-esser. I needed a de-esser one day, and there was no de-esser around. It was about a year and a half ago. I said, "Hey, there's a compressor. I wonder what happens if I stick a filter into the side chain. Whoa, it's a de-esser!" The knowledge of how to process the audio is just stuff that anybody good in this business picks up from reading the magazines and reading the text and reading the equipment manuals. I probably learned more about processing from reading every manual I could get my hands on than anything I could have learned in a school. Orban's manuals, especially. No matter how dry and stiff they are, you're still going to learn something about the circuit, and the more you know about what that box is trying to do, the more you can make it do tricks.

RAP: Would you say it's more important today to read the manuals than it was ten or twenty years ago?

Jay: No, I don't think I would. The technology keeps on exploding, but ten or twenty years ago there was still plenty to learn. When the first Orban stereo simulator came out, there was a section of the manual that explained how it worked. Once I knew how it worked, then I was able to use it as a special effect in mono, or I could do other things to it. Take the first Eventide Harmonizer, the model 910 back in 1976 or 1977. You opened up the manual, and Richard Factor had written an elegant description of how time compression works--how you change the pitch of something in real time. I bought a mike preamp and put it in this weekend. I was looking through the manual. The manual is a gem, an absolute gem, and I learned some stuff about avoiding ground loops.

RAP: ISDN is getting a lot of talk these days. What are your thoughts on this technology?

Jay: It's the latest, greatest thing. It is wonderful. But it's going to be obsolete in three or four years because somebody will invent something better. Certainly the technology that we're using, the MPEG Layer II and III, even the AptX and the Dolby Fax, those are going to be supplanted within a couple years by better technologies.

RAP: What is the best quality available now over ISDN lines?

Jay: It depends on the bandwidth. If you've got infinite bandwidth, the best quality is 16-bit linear. Nobody's got that. If you've got three ISDN lines, six individual channels, if you're willing to really pay for it, the best quality is probably the 3D2 system which uses AptX compression. The 3D2 is not so much a box as a network. They buy the phone lines. They charge you an outrageous amount per hour to use those phone lines and a monthly rental on the box, and at the end of the year, they own the box. But it's very good quality. With a little bit of tweaking, the quality approaches 16-bit linear, full bandwidth, 20-20K.

RAP: What codec are you using with ISDN?

Jay: I'm using the Zephyr now with Layer III, single ISDN pair, basic two conductor copper wire. It's actually a drop that was used for an ordinary telephone, and the phone company switched it over and said they were going to use this pair for the ISDN. Dirt cheap. Costs me in the vicinity of fourteen bucks an hour. I get 20K bandwidth stereo, bidirectional. I did a session Friday where I directed an announcer in Miami and recorded him in Boston for a promo for a radio station in Salt Lake City. He was right there on my monitor speakers. It sounds a tiny little bit fuzzy, but it sounds better than FM radio. It just doesn't sound quite as crisp as when I'm recording the guy here.

RAP: How much compression is being used with the Layer III?

Jay: That's twelve to one compression with the Zephyr MPEG Layer III.

RAP: Has this compression presented itself in any nasty ways down the line?

Jay: No. I haven't got any complaints. I do the one pass and I mix it with other elements, and I do a little bit of equalization and some other tricks to it to make it as clean as I can. I have a generalized voice processor that I wrote for the Eventide to fix up signals as they come in off the Zephyr, but even the raw signal coming out of the back of the Zephyr is music quality. A little more distortion than we're used to these days and a lot better than the best MTR10 or MTR12 ten years ago.

RAP: Is this bit of distortion a result of the compression?

Jay: Yeah, it's from the masking. It's not that they compress the signal down twelve to one like you would with PKZIP. It's that it goes through and decides what it is that most listeners won't hear. For example, if you've got a real loud sound and then another softer sound at almost the same frequency modulating it, very few people will hear that softer sound. So this strips them away. Then it says, okay, I've got much simpler data, and sends it down the line. At the other end, it gets instructions to spread out that simpler data as if it were the entire sound. Similarly, you take a very loud sound and follow it in time by a very soft sound, even if they're not related at all in frequency. Most people won't hear the soft sound. It's also the secret of Stan Kenton's band arrangements. He would modulate by doing a big, loud drum riff so that when he came back, everybody would have forgotten what key it was in.

A couple of companies--if I could put in a plug here, not only for Telos but also for Comrex--are working real hard at educating us poor schnooks in the studios, telling us what's what with these algorithms, making it possible for one box to talk to another.

RAP: The Zephyr seems to be the codec that keeps coming up in conversation. Is this the best one out there?

Jay: If you can afford it, it's going to be the most versatile and will pay off the best for you. If you can't, if you don't have five thousand bucks to sink into it, Comrex has some lower cost boxes that do a very, very good job and that cross connect with the Zephyr, maybe not 20K bandwidth stereo, bidirectional, but 15K over a single ISDN line--just the thing for a voice.

RAP: And when you say bidirectional, you mean you can be talking to the person on one side of the line while they're sending the audio down the other side?

Jay: Yeah. And there's a slight delay in all these systems except for the real expensive 3D2. They store up half a second of sound and looks at that half second and say, "okay, here's what I'm going to do to save some data." So Nick Michaels talks to me from Miami, and I hear him a half a second later. I give him an instruction over the talkback, and he hears it a half second after that. I've got a couple of relays in my talkback system so he doesn't hear himself a whole second later, which would throw anybody off. There are work-arounds.

I do a lot of stuff where I rent studio space at Westwood One in New York. I get a New York announcer in there at Westwood and I'm directing him on one standard leaving the Zephyr, and they're sending back to me on a different standard coming back to my Zephyr. So I'm getting 20K of announcer, but he's only hearing 7.5K of me, which is still fine for directing, but he's hearing me instantly.

RAP: What are your thoughts on digital delivery systems like DGS or DCI? A lot of stations are on these networks.

Jay: Those are both very good systems. I looked into them and decided they wouldn't do for what I'm doing because they charge by the minute transmitted. If you have one spot to get to twenty stations, and you want it to be there in four hours, it's a great economical way to do it. It does use data compression, but if you don't need it instantaneously, it works. The problem that I had was that if I did a twenty-minute session, they charged it like twenty spots, and it isn't real time, even under their best service. So I'd have to direct the guy on a phone, and if I'm going to do that, he might as well FedEx me the tape.

RAP: You have a directory of ISDN equipped studios on your Home Page. How did that come about?

Jay: When I first got the Zephyr a little more than a year ago and looked around, there was one company, DigiFone, that had a list. You pay thirty bucks and you get four or five Xeroxed pages. Most of the sites on it were commercial recording studios using the three hundred dollar an hour system. I said, "I don't want this." So, I posted a note in the Broadcast Forum on CompuServe and in the rec.radio.broadcasting news group and told some friends. I called Telos and said, "I want to gather this information and make it publicly available to anybody who wants it totally free with no liability on my part. If you call somebody on the list, you work out your own deal with them. I want to do this just because nobody else is doing this, and the data should be out there." So Telos cooperated very nicely and said, "Well, we're not going to let you put out names and addresses from our guarantee cards, but we will give you the fax numbers so you can send a solicitation. And if they want to be on your list, they'll give you the rest of the information." Comrex has done the same thing quite recently, and by the time this interview comes out, I'll have a bunch of Comrex sites on there, too, since they're all inter-operable. One of the other manufacturers made nasty legal noises and said I can't even mention their box on my list, and I made nasty legal noises then and said, "Fair use--I'm a journalist and if somebody says they have your box, I'm going to report that fact." So they went off in a huff.

RAP: You are Vice-Chair for the Boston Section AES. How did that come about?

Jay: They needed somebody who knew enough about advertising to be able to put together the newsletter. The local section had also been very technical and very "technoid." There are a lot of very good people--incredibly gifted circuit designers, speaker designers--the people who actually understand what's going on at the electron level with the things we deal with, but the meetings were so full of math that only those guys could understand, and there was very little participation by the local advertising or production community. So they asked me to join the Executive Board then a year later be Vice Chair and see what I could do to goose it a little bit for all those other audio engineers, the guys who show up at the New York AES but never attend the Boston section meetings.

A lot of this, the ISDN list I do, the AES, and even to an extent the writing I do in Digital Video magazine and a couple of other places, is trying to bring back something to the community, because when I was twenty-five, there were a lot of people who were very good to me. I've had my gurus.

RAP: Which gurus come to mind?

Jay: Probably the most important would be Tony Schwartz from New York. Sound designer extraordinaire. Sound philosopher. He was the one who conceived the Goldwater-Johnson daisy spot if you recall that--classic piece of political advertising. It communicated everything and said absolutely nothing. He's written a couple of excellent books on the subject of how thoughts get from one person's brain to another via sound. He teaches. He has a Chair at Fordham University, Harvard University, and Emerson College. He invented mnemonic speech.

He was very good to me. He would listen to my tapes and encourage me and talk about what I'd done and suggest other things I could do. You know that basic technique we all do in announcer spots where a person is talking and then his own voice overlaps it? He invented that. He was the first person to ever do it in the promos for the movie Woodstock in 1969 or 1970.

I saw an article in BME. Back in the late sixties it was a very hot little magazine with a lot of interesting stuff in it. There was an article on what he had done and it explained his technique and talked about other things he had created. I started playing on my little 2-track Ampex in my living room, trying those techniques, and I wrote him a letter. He wrote back and said, "Sure, come on down and talk." So it's for him--and for the instructor at Emerson who said I'd never be a star DJ but could probably be a writer. That's why I try to help the community and make sure there's another generation of good radio people coming up.

RAP: You mentioned that you write for DV (Digital Video) magazine. Is this a regular column?

Jay: Yes. I do a monthly column in DV which I try to keep as down to earth as much as possible. I explain the technology to videotape people and use video analogies to explain things like sample rate or where you place the microphone in a room and how moving the microphone a couple of inches either way can make a big difference in the guy's voice. I've also written maybe a half dozen features for them and occasional articles for Back Stage, Videography, and various places like that.

RAP: What advice would you offer someone in radio about making a move into what you're doing?

Jay: First thing you gotta do is either have a very understanding shrink or a very understanding wife or not give a damn because it is a major risk. You'll be eating a lot of Kraft dinners because what you have to do is go from the secure nine to five with paycheck where you don't have to pay for any equipment to a situation where basically you're selling yourself to the ad agencies. You've got to get a relationship with them where they hear what you've done, where they hear why it's unique, why you've got something more to offer than the studio down the street where they'll put a CD in and record your announcer and top it and tail it and say, "Here you are."

I get a lot of e-mail and phone calls from people who see my Home Page or they've heard stuff I've done and they ask, "How do you make that jump?" You have to be willing to play with a year of your life. When I started doing this, I was selling six days a week so that I'd have something to do on Sunday so I could make some money. I went to the agencies explaining my reel. It's marketing, and you can't do it part-time. You can't do it while you're working at a station because the guy paying your salary will always have the priority on your time. You've got to spend a long time pounding pavement and convincing your potential customers that you are unique.

I think what also makes a difference is that I don't use my own voice very much. So you listen to my reel, and there's a lot of different talents on it that you can pick from. It's not all Jay voicing them.

RAP: You must direct a lot of talent. What are some tips you can pass on about directing voice-over talent?

Jay: Know exactly what you're looking for before the guy walks in the door, and be prepared to accept something better. Have an image in your head of exactly how that spot should sound, every syllable of it, but don't stick with that image if he's coming up with something better.

Second tip. For most good talents, don't give them line reads. Don't ever give someone a line read unless you're absolutely sure of your own chops. Don't pick up the copy and say, "Well, George, what I want you to say is 'Tonight on WBZ you'll hear'...." It's a lot more efficient to say something like, "Look, guy, it's real important that you bring out the word tonight." What happens a lot--and back in my days of punching the buttons while other people directed, I heard a hell of a lot of this kind of thing--the director would say, "You said 'give it a crumb crisp coating'. What I want to hear is 'give it a crumb crisp coating', [sounding just like the previous read] you see, with the accent on coating." That gives the actor less than nothing to go on. Don't read it for them unless you're absolutely sure that the one thing you're demonstrating is going to come through, and point it out.

Another thing, pay a lot of attention to every syllable of what they read. Don't just say, "That was a good take. Let's do it again." Be more specific in your notes. "In the third paragraph I really need you to bring out the name of this product a little bit more because it's the first time the audience has heard it. When you get down here to the slogan--they use that slogan in everything--you can toss it off, but take some real pride in this word over here." A good actor/announcer can respond to that. And if you see they're not responding, then you give them a line read, but make sure your line read agrees with the direction that you gave.

I'll give you another tip. Don't be afraid to back down. A lot of times I will say to somebody over the talkback, whether they're in my studio or five hundred miles away, "Hey, you gave me exactly what I asked for, and it's not what I want. Let me try something else." It's not their fault. A lot of directors think directing is an adversarial process and you get points by being better than the actor.

I've worked with some fairly heavy name actors--James Earl Jones, Christopher Reeve--on voice-overs, and there's a process of about four or five minutes at the beginning of the session where they're the actor and you're just this advertising guy. But after a couple of minutes, they realize you're trying to make them sound better, and you realize exactly how much commitment they're willing to put into the project. And from then on, it's golden.

RAP: You've had your fair share of building studios and are presently working out of a very nice home studio. What advice can you give someone about to do the same.

Jay: You need a good ergonomics base, which means you probably cannot do it on a desk in your bedroom. This is an important distinction. I don't have neon in my place, but I do have a big counter top that puts the workstation at the right height for me. That's directly in the sweet spot of all my monitors. You've got to pay a little bit of attention to the acoustics, and there's been too much written on that for me to take up twenty-five pages of your magazine. But from the standpoint of room treatment and absorption and standing waves, as well as keeping the outside noises from getting in, you've got to pay some attention to that.

You've got to have some good libraries of sounds to work with--a good sound effects library, a good imaging sounds library, a good production music library if that's the kind of work you're going to be doing. Of course, all of these should have the proper clearances on them. You can't steal music. You can't steal sound effects.

I'd say these days, if you've got any musical ability at all, you probably should have a synthesizer because there are so many sounds that you can just walk over and grab. With a lot of my stuff, I'll use library music for nine-tenths of a spot and play one-tenth of it on a Kurzweil. I'm not a particularly good musician, but I know what I need for those six seconds.

And these days you've got to have an ultra-clean digital chain. You can't do it on a half-inch 8-track anymore.

RAP: A lot of people doing home studios are looking at the software based systems they can plug into their PC or Mac. Are you familiar with any of the audio software that's available?

Jay: I'm much more familiar with the Mac than the PC, and I have just about every piece of Mac software for sound that exists because I write about it. I have Deck, DigiTracks, Premiere, Sound Designer. I don't have ProTools. I can't talk too much about that except to say to make sure that it's a system that does all you need when you need to do it, not just something that has a good spec sheet or looked good in the demo video.

Obviously, I'm committed to the Orban DSE-7000. The reason I'm committed to that system is that it lets me do what I need to do quickly and with a minimum of hassle. When I have an ad agency guy here and he asks for something, I've usually got it edited before he's finished with the question. "Can you take that syllable and put it over here in the middle of this word?" "Sure." And that's important to creativity--to mine...to heck with his. If I think of an idea, I want to be able to try it immediately. Now, granted, a lot of people setting up in their homes cannot afford a twenty thousand dollar workstation. I'm also amazed at how many people setting up in their homes have afforded a twenty thousand dollar workstation. I made my choice based on the speed and the power. I know what's out there on the Mac, and there are some wonderful, wonderful things you can do with a Macintosh for five hundred bucks. With a current Power Mac, the audio in/out capability is certainly as good as an analog deck of ten or fifteen years ago. I wouldn't say it was a full sixteen bits worth of CD quality audio, but it's at least fourteen bits worth. And a program like DigiTracks or Deck can let you do some amazing production work in a hurry. It's just nowhere near the kind of speed you need for modern production.

What else is important is to make sure you've got some real effects, not just the echo or tone controls some anonymous programmer put in. You need good compression and EQ. Compression and equalization are the primary things you have to do in radio. That's the effect you're going to use on every element, and it's got to be stuff that you can hear in real time. And it's got to be absolutely clean. I had a whole rack of Orban compressors and equalizers long before I ever started working with the company, along with some Gain Brains and some Ureis and a whole bunch of other gadgets. What else? Good monitors. So much stuff that you hear on the air is obviously mixed on a bad monitor. I monitor with a pair of 4410s in the near field, a pair of hi-fi style speakers, plus a pair of Auratones. They're all in the near field, which is real important in a home studio because you're not going to have an acoustically tuned room, a room that's flat, and you don't want to equalize the speakers. A little bit of tweaking in a music studio, yes, but if you're concerned with distortion, why do you want to add distortion to the monitor speakers? I can sit at the Orban workstation, in the center line of the room of my studio, and pop between the Auratones, the 4410s, the hi-fi speakers and even the little three-inch speakers in my TV monitor, and the only thing that changes is the quality. The sound field doesn't change, and the level doesn't change. You hear an awful lot of stuff that is mixed on bad monitors, and you can tell when you hear it on the air. There's a missing mid-range, usually, because the monitors are slightly honky. Or the monitors have this hi-fi brightness and everything that comes out of the monitors is sparkly; and you put it on the air and it's all muffled.

RAP: Anyone who has ever carted up agency dubs will tell you that the EQ, mixes, and other processing will vary greatly from one set of agency spots to another. Would you say poor monitors is to blame for a lot of that?

Jay: I wouldn't know what to blame for it. I worked real hard when I was running the downtown studio to keep a consistent sound. We put pink noise on every master and ran it through the high speed duplicator so that we could pull dubs at random and make sure the entire duplication chain was flat. A lot of the time you've got two different studios on the same block of a big city with two different monitoring philosophies. One of them is a music studio. It's big with loud monitors that are going to knock you over. They think, "Who cares about the mid-range? That's not important for the music!" Then you have another studio where maybe they're mixing on Auratones and they have no idea what's going on at the top and bottom of the range. Then you have an ad agency producer who has no concept of acoustics who says, "Gee, that sounds good here; I guess it's done." And I've been guilty of it. When I first started working at the mega facility, there was a brand new 24-track room that had been designed by one of the top name guys. I went in there and started mixing and it sounded fine. I had no way of knowing that he had beamed the high end right at the engineer's mix position. So I did a mix that sounded good, and we put it on the air and there were no highs. One thing you've got to do is listen to your stuff on the radio as much as possible on as many different radios as possible. If it's not going on your own air, find out where it is going and listen to it. Don't just listen on an air monitor in your production room, but tune in your stuff while you're driving around. If it's on different stations, listen to it on all those stations if you can. And learn what you're listening to.

RAP: What are some of your favorite microphones for voice-work?

Jay: In my situation, I am very much partial to the AKG 451 CK8 series short shotgun, because in a less than perfect room I can point the microphone and do some wonderful things about ignoring the room acoustics. I don't believe that a microphone has to be warm and boomy and all that in a piece of production work. It's more important that you get a very accurate sound, that you get a very clean sound that's full range.

RAP: You have an appealing and informative Home Page on the Internet. What value do you see with the Internet now and in the future with regards to our industry?

Jay: Well, the first thing people usually ask me is how much work have I got after having such a great Home Page, and the answer is zip. I've gotten one inquiry that didn't develop into anything. However, I got at least five dozen demo tapes from other people. Not people who I'm likely to use, but they found me there so they sent me a voice tape.

At present, I think the value of the Internet, the value of the World Wide Web is just that it's out there, and we're still figuring out what it does. In another year or so people will probably turn to it as a steady resource. I use the Web when I'm researching stuff--how a particular compression algorithm works or what the copyright implications of a piece of music are. It's useful information, it's all out there, and it's free. Likewise, when people want to find out where they can send an MPEG Layer II signal, they look at my Home Page.

There's another part of the Internet, though, that's very, very useful, and that is the news groups. I learn a lot and I get to share a lot in the rec.radio.broadcasting news group and in the rec.audio.pro. Now that the commercial services all have news group access--quick, before the government shuts the whole thing down--take advantage of it.

RAP: What about transferring audio files on the Internet? Do you do very much of that?

Jay: I do very little of that. It just isn't fast enough. High quality audio needs a heck of a lot of compression. I transfer magazine articles and photographs. The Internet is terrific for that.

RAP: What's your "production philosophy?" What is it that you do that you feel makes you successful?

Jay: I think it's enjoying my work. I love what I'm doing, because playfulness is a part of creativity, and we're in a creative business. You can't get up in the morning and say, "Oh, God, I've got to crank out ten spots today," because they'll sound cranked out. So I keep on playing. I play with different sounds. When the client thinks it's good enough, I'll say, "Hey, let me just try something here." Half the time I'm way off base and I've wasted three or four minutes of his time, and half the time he'll say, "Hey, that's a good idea."

I used to think you could never be satisfied with a project. I had a film producer tell me that no film is ever finished, it's just taken away from you. I used to think that about the mixes, but then I realized no, no. On a lot of stuff, I know when it's done and it satisfies me. What's great about the stuff I'm doing now or have been doing for the past ten years is that I can take a tape off the shelf from ten years ago and listen to it, and it's still good. On the other hand, the closest equivalent to doing real radio in the advertising world is politicals. We've got very little production time to get something together to get a message across that somebody had very little time to write that has to respond to a problem immediately and has to get on the air in four hours. I listen to politicals I have done that I thought were real good at the time, and they're not. They're a clever idea, period.

The other piece of philosophy I've got is "polish." That's where the Orban is such a godsend. Any system can let you record a voice over a piece of music. With the DSE I can go in and in two or three minutes take out all the breaths and totally change the pacing. In a minute I can stretch how he reads the signature line. I can do the mix and then go back and mix from the third second to the fifth second only.

♦