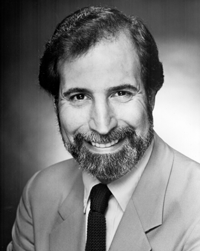

Dick Orkin, Dick Orkin's Radio Ranch, Los Angeles, California

Newsweek has called Dick Orkin's Radio Ranch, "the established masters of the Advertising Theater of the Absurd." L.A. Magazine describes his voice as, "A schlemiel adrift in a surreal sea of supermarkets." Listen to his demo on this month's Cassette, and you'll say it's some of the best work you've ever heard. After attending Franklin and Marshall College in Lancaster, PA then the Yale School of Drama, Dick returned to Lancaster as News Director for WLAN. From there it was off to KYW in Cleveland as the News and Public Affairs Director, then to Chicago and WCFL as Production Director where Dick's long running radio serial, Chickenman was created in 1968. It wasn't long before Dick's talents took him out of the radio station and into his own commercial production company which, to date, has picked up more than 180 advertising and radio awards. When not busy cranking out some of the nation's best commercial production work, he's sharing his expertise in various workshops throughout the U.S.. He's easily one of the greats in our industry and gives us a wealth of insightful information to absorb in this month's RAP Interview.

Newsweek has called Dick Orkin's Radio Ranch, "the established masters of the Advertising Theater of the Absurd." L.A. Magazine describes his voice as, "A schlemiel adrift in a surreal sea of supermarkets." Listen to his demo on this month's Cassette, and you'll say it's some of the best work you've ever heard. After attending Franklin and Marshall College in Lancaster, PA then the Yale School of Drama, Dick returned to Lancaster as News Director for WLAN. From there it was off to KYW in Cleveland as the News and Public Affairs Director, then to Chicago and WCFL as Production Director where Dick's long running radio serial, Chickenman was created in 1968. It wasn't long before Dick's talents took him out of the radio station and into his own commercial production company which, to date, has picked up more than 180 advertising and radio awards. When not busy cranking out some of the nation's best commercial production work, he's sharing his expertise in various workshops throughout the U.S.. He's easily one of the greats in our industry and gives us a wealth of insightful information to absorb in this month's RAP Interview.

RAP: Describe a typical day at the Ranch.

Dick: Well, the first thing we do in the morning is review the work we did the day before. We take a look at the writing and at some of the brainstorming sessions we've had. We usually do that for about an hour. Then we discuss areas where we need to clean up and fix up whatever work we've done the day before. Then around eleven o'clock, eleven-thirty, we usually have our first briefing of the day with an advertiser, unless they're on the east coast, in which case it tends to be a little earlier than that, around ten o'clock. Then after the briefing, we're usually in the studio or writing, one or the other.

RAP: When you're in the studio, do you ever get the urge to sit behind the console and play around with the toys?

Dick: No, no. I'm a producer/director/writer/performer, not a production engineer. We have two production engineers.

RAP: Was WCFL the only station where you were Production Director?

Dick: No, I was also Production Director/Public Affairs Director in Cleveland at what was then KYW radio.

RAP: How did the Chickenman get started at WCFL?

Dick: It was about 1967 when the Batman television show was very big. It was sort of an overnight sensation. My Program Director, Ken Draper, suggested we create a superhero since we seemed to be in that superhero camp comedy style at the time. He came up with the notion that I develop a superhero for each of the personalities on the station, and the one that I developed for Jim Runyon was the one where I played Chickenman. There were others for the other personalities that lasted maybe two or three weeks and another that lasted almost a year. But the Chickenman went into syndication.

RAP: Is Chickenman on the air anywhere these days?

Dick: It's probably in about thirty or forty markets.

RAP: Are you still producing some episodes or just running the old ones?

Dick: I haven't produced them for almost twenty-two years.

RAP: Was this your first jump into comedy writing and producing?

Dick: No. Prior to coming to WCFL radio in Chicago, I had been a free-lance writer of both advertising and comedy features for various radio stations, usually three and a half, four minute features that ran throughout the day. They were sometimes contest comedy features or seasonal comedy features. Back in Cleveland, I did a two and a half minute feature that ran for two weeks before Christmas called Angryman. This was probably the antecedent of Chickenman. Angryman was a guy who just got so absolutely irritated at all the pressures of the Christmas season that he exploded and became someone else.

RAP: When did you decide it was time to leave radio and go out on your own?

Dick: Well, that was in Chicago where the trend in radio was moving away from what I called entertainment or programming-content radio into just music and brief talk. They had a rep firm, and the rep firm hired a consulting firm which moved the format to a minimum of talk. It was just time, weather and station IDs, and the rest was all music. That was not something I could have any fun in. I tried to make it work for about six months to a year, but it didn't. I finally gave up the ghost and decided to go into business for myself producing radio commercials for many of the advertisers I had been working for prior to that time in Chicago. Many of the major agencies, as a result of Chickenman and other things, had actually hired me on a free-lance basis to write and produce commercials for them, so I just decided to do it full-time.

RAP: What was your first major account?

Dick: Purple Martin Gasoline. That's where I dressed up the attendants in purple tights. They weren't getting any attention in the marketplace, and that got them attention. We did spots about the fact that if you drove into certain Purple Martin service stations, you would see their attendants in purple tights and, boy, was that a job convincing them--the attendants, not the bosses--to wear the tights. The bosses liked the idea. They had hired me to do radio, but we extended it into the sites, and that turned it into a different kind of campaign. It got them an awful lot of attention--photos in the newspaper and so on.

RAP: What are some accounts you're working with right now that our readers might recall hearing?

Dick: Currently, we're working for Pepsi, John Deere Lawn and Garden Equipment, Seiko Message Watches, Carlsberg Beer, First American Bank of Chicago, and U.S. Health Care. That's six out of maybe forty clients.

RAP: Do your clients stay with you for a long time, or are you always shopping for new clients?

Dick: Our radio production business is a little different than the agency business because we tend to retain clients. I'd say eighty to eighty-five percent of our work is just the continuing business of working for clients who hired us the year before, the year before, and so on.

RAP: Are these clients that might have switched agencies over the years while keeping you on?

RAP: Are these clients that might have switched agencies over the years while keeping you on?

Dick: They've switched agencies sometimes two and three times. In fact, if the new agency doesn't want to work with us, sometimes they fire the agency and just hire us. That has actually happened.

RAP: One of your workshops deals with a Radio Ranch method of idea-generating based on a process called DWE? Tell us a bit about this.

Dick: DWE is Dialogue With Experience. This isn't something I'm going to be able to explain in a few words because it's an all-day workshop, but the process really involves what I call a post-modern technique of advertising. Instead of copying or cloning or imitating other advertising campaigns and seeing the consumer as someone you do something to, what you do is decide you are the consumer. It's called making yourself the customer, which is not a new idea. Most of the advertising greats always believed that was the way to approach creative concepting for advertising. Leo Burnett said to his copywriters and to his advertisers, "If you can't become the client, get out of the advertising business." So, we take that literally and call upon our own experience, not necessarily with that particular product, but in a like category, and we invade our own psyches in order to come up with some creative material--our memories, our experiences from our family life, from our media life--that we can then use by a three or four stage program to develop into advertising ideas.

RAP: Is this part of the seminar, "Radio: Ad Crafting with Soul?"

Dick: Yes. The idea is to find and create an emotional connection between you, the creative person, and the radio audience. Radio has been doing that for a long time. That's why it's called the personal, up close, intimate kind of medium because it has that capacity to form that relationship. Strangely enough, that's what all of the new post-modern literature today seems to be talking about--forming a relationship to the consumer. And I always point out with some pride, and maybe some people would say arrogance, that radio has been building that relationship for a long time.

RAP: What are some other major topics that you cover in this workshop?

Dick: Well, I review what I call radio detours, where radio gets off the road sometimes because it's still connected to what's sometimes called a persuasion model of advertising, which is really a modern concept. It's very rational and logical. It says to people that you should buy this because it will be good for you or it will provide these benefits to you. It's that "unique selling proposition" idea, but there's such a parity of products and services today that one can't really talk just in terms of a unique selling proposition anymore. So, in the content of the message, in the style and tone of the message, you need to do something that goes beyond just the persuasion model. What I do is talk about how radio gets off track sometimes with that persuasion model and believes that radio advertising is about words, and it's not. It's about ideas, emotional ideas in particular. So I spend a lot of time talking about what I call the detours that trap people, particularly local and regional advertisers, into doing radio advertising that doesn't use the medium to its fullest extent.

Then I spend some time talking about performance, which is a major issue for me. I'm talking about the voices that are used to either produce or just do radio commercials live. My own opinion is that the performance is key to the success of an advertising campaign. So I spend some time talking about either directing, producing or performing in radio commercials which, by the way, is what Dan O'Day and I will be doing at our workshop here in Los Angeles in August. It has a very lofty name. Dan called it the International Radio Creativity and Voice-over Summit. I think he changed Voice-over to Performance. The idea is that we're going to talk about both the words and the spirit of the time for radio because on the eve of the twenty-first century, both the spirit of the time for advertising and, therefore, the words have changed. In different ways, we each focus on that issue in a series of workshops and panels. We're hopefully going to have some advertising creatives, management creatives, the hot shots, come in and talk to us about how they see radio playing a role in the new spirit of the time.

RAP: You also have some voice-over workshops. Tell us a little about these.

Dick: One voice-over workshop is called "The New Art of Radio Advertising Performance." That's an all-day workshop. Then I do a half-day workshop that I've done with Dan in Dallas and I'll do again for this event in August that's called "How to Make Everything You Do on the Air Your Own." It's sort of a radio personality application of our advertising workshop, "Radio: Ad Crafting with Soul." "How to Make Everything You Do on the Air Your Own" really has the same kind of goal behind it, and that is to take personal experiences and transmute the material you're working with. It may be a joke you picked up from somewhere, or it may be some kind of material you picked up off one of the wire services. Whatever it is, you filter it through your own experience in order to make it more personal. There are a number of those workshops coming up all over. I think the new schedule for the workshops just went up on the Web site. I'll be doing those in Kansas City, Baltimore, Boston and a few other places in 1996.

RAP: More and more, we keep hearing how the agencies don't want radio voices on their commercials, that voice that so many people in radio have acquired over the years and have so much trouble getting rid of. That's true now more than ever, wouldn't you say?

Dick: Yeah. In fact, I did a piece for CompuServe that was from the Performance workshop, and that's precisely what the article is about. It's called "The Packaged Radio Performer, Dick Orkin Comes to Bury, Not Praise." What I'm suggesting is that what continues to hurt radio in terms of its joining mainstream advertising media as an effective ad medium, is the tendency for management of radio stations to allow DJs to continue this kind of what I call cloned radio sound. I mean, they learned it from another DJ. They said, "Oh, that's what a DJ should sound like." If you think of the parody that Gary Owens did and still does, when he cups his ear on the old Laugh-In show, that's precisely the sound that comes out. There's a guy by the name of Mitch Albom who did an article for the Detroit Free Press who says that the problem with that voice is that radio sounds alike today, all the time. And because there is that kind of sameness of format no matter what part of the country you're in, you'll hear that same sound. He calls that the homogenization of America by radio formats. I think his analysis of why it happens is wrong, but I agree with him that it's happening, and I urge radio station management, and I urge radio producers and agencies to avoid that listening to your own voice kind of sound. I still get audio tapes from people that say, "people tell me I have a voice of God sound." What I want to say to them is, to quote the Nietzsche thing, God is dead; now get a life because that's what the people really want to hear.

It's a continuing problem, and part of my goal in my workshop and my classes here in LA is to get people to drop that kind of radio "back in the throat" sound. I do that by applying that same technique that I use in "Ad Crafting with Soul," making the text their own. There's a very famous writer and teacher of speech and radio and theater in London, Patsy Rodenburg, who says that the solution for all performers is to remember you're telling a story and you've got to make the text your own. That is the major goal of all my workshops, the classes and this larger workshop, to show performers how to take the text and make it sound like their own and not just do a "hand cupped behind the ear" radio voice.

RAP: Making the text their own...this is something actors do all the time. We're talking about turning radio announcers into voice actors.

Dick: I'm convinced that performance in radio today is an acting skill, and some of the people from radio stations are naturals. Arthur Godfrey was a natural in many ways, and Howard Stern is a natural. Rush Limbaugh is a natural in many ways. They're actors, and if you don't have that, then go take an acting class is what I urge people to do. You need that. You can't make it in competitive radio voice-over today without some acting instinct driving your performance.

RAP: How many acting classes are we talking about? For how long should a radio production/voice-over person take acting classes?

Dick: I think you take as many as you need to get the job done. If you're a rotten actor, we're going to hear it on radio. I have a number of television and radio news people who want to make a switch and move into voice-over. They're going to have great difficulty doing that because that news voice is so totally imbedded in their vocal style that they really have to struggle to get it out of there. What we do to loosen them up is improv exercises, which is sort of a contemporary approach to acting these days anyway. I have a great friend in Avery Schreiber here in Los Angeles who teaches improv. What I do is send most of these news people to improv classes to get some freedom, to break up some of the rigidity in their approach and in their style, to feel free to use some of their environment and their experiences in their communication style.

So the answer to the question is they have to do it as long as it is required. Some people can get it right away. Eric Tracy is on KABC radio here. Eric came to my classes for five weeks and one day it clicked for him. He suddenly understood what it was he needed to do to talk to people in a more direct way, and he didn't take one acting class. It just came to him as a result of something I said or something he said to himself. For some people it will be an instant kind of thing, and for others it's going to take longer.

RAP: What are a couple of your basic rules to writing comedy dialogue?

Dick: If you're writing dialogue, make sure the people are really talking to one another. You can best do that by having a conversation yourself, speaking the words aloud. The problem with too much terrible dialogue copy is that the writers are just sitting in front of a word processor, and they're either saying it silently to themselves or they're not performers. The result is a very stilted and un-conversation-like dialogue, and what it does mostly is just include a laundry list of features and points. But it doesn't sound like the way real people talk. To get close to the way real people talk, you need to really dialogue that with yourself.

RAP: What are some other common mistakes you hear on radio spots?

Dick: Too many sound effects when they're not necessary, sound effects for their own sake. Sound effects are supposed to be like scenery and lighting on a theater stage, a means to an end. People forget that with radio. They use sound effects for their own sake, and it doesn't work. It calls attention to the sound effects but not to the message. The sound effects are there to call attention to the message and dramatize the message.

In radio, there's also a tendency to believe that merely creative is okay. In other words, as should be the case, people have a very broad definition of what creative means in radio, and sometimes, just making a lot of noise and having DJs shout, putting in lots of sound effects and maybe one or two funny lines that someone thinks are funny, is what people regard as a substitute for creative, and it's not. It is a surface attempt at the creativity process. And if you put it against some of the truly clever advertising in television and radio, not the least of which is coming out of television, then it just doesn't measure up. Radio's copy doesn't measure up to those kinds of clever ad campaigns that are out front, that really are rooted in something more than just self-conscious sound and vocal exercises.

RAP: There's definitely a lot of boring ads on radio, and I think a lot of that comes from managers who enforce an unwritten policy that says if a client wants a spot to start tomorrow, it starts tomorrow...just throw something together.

Dick: Well, radio has come to believe this notion that it has the capacity to respond instantaneously. Remember years ago, most of the RAB campaigns and most of radio's own local and regional promotional campaigns were focused on this notion of instant responsiveness. "If you're going to have a sale and solve a problem that you have moving a product, we can write it today and get the product moved tomorrow." That may have been true twenty or twenty-five years ago, but radio now has become such an electronic post-it note in the world of advertising that it's just a series of electronic post-it notes everywhere you go. As a result, with the parity between all these products and services, just informing people doesn't make a difference anymore. Just announcing it doesn't make a difference anymore. You need to dramatize it. You need to tell a story in some way. You need to find some unique and clever way to focus on what is the major selling proposition. And it's hard not to use the term "unique selling proposition" but you need to find a way of demonstrating that through story telling or some kind of dramatization. And you don't have to do dialogue to make that happen. Most radio stations are convinced that when I say story telling I'm talking about story telling in a dialogue sense--you have an expository thing at the beginning, then you have a middle, and then you have an end. And they also think I mean humor, and I don't. Story telling can be simply a matter of single-voice copy with a headline proposition at the top that grabs us, that compels our interest because it relates to our own lives, relates to our own experience. And words alone won't do that. Radio is really bound up and management, particularly, is bound up in this notion that radio is simply about making announcements, and that if you announce, people will respond. It just isn't true any more. It just won't work like that.

There are exceptions to that, of course. Sometimes the announcement is truly of such significant and substantive news that it will work just by saying it. There aren't many situations like that anymore. There are very few car dealers who truly have a competitive point of difference. They are all pretty much the same. We're, at the moment, advertising some new computer technology products. We just did spots for First Aid, sort of a fix-it program for sick PC computer programs. It's called, I think, Deluxe First Aid. We're doing another one for a voice technology device that you train with your own voice that remembers phone numbers then plays it back when you vocalize it. Those ads we can do easily by demonstrating, and there doesn't have to be a major story with it. It's truly news in the sense that advertising was once. If you had a product or service that was brand new, the news of that newness was sometimes enough because there wasn't anything else like it in the marketplace. We don't have that many advertisers who can make that kind of claim anymore. And you're right, it is management believing that the solution to it is simply put it on the air and people will respond to it. There's a kind of presumptive arrogance about how people listen to their radio station or listen to radio. And you may get a few, but you won't get enough response to be competitive with print and television. And that's why print and television win out so often over radio.

It just takes the time to understand the nature of advertising and, unfortunately, radio management has not invested a great deal of money in understanding the nature of advertising or the nature of the consumer. They're quick to spend money on finding ways to get salesmen motivated to go out and sell, and what I call the contractual arrangement between the radio station and the advertiser that involves signing a piece of paper that says you pay us this amount of money and we'll run this many spots, is only one-half of the contract. The other half of the contract is that you get results, and that part, in terms of investment of energy and money, seems to be the most neglected. As a result of that, I think radio suffers.

RAP: Do you see this attitude changing?

Dick: Oh, it is changing, but it's changing much too slowly. If radio wants to take its place alongside the mainstream advertising media in 1996, it can. The potential for doing that is powerful with radio and has been for years and years and years. Some people are willing to take the time and make it work, make the investment of energy and focus and money to make it work. Some are not. And there are many radio stations in the country who do that. I've gone and spoken to them, and later, on a follow-up, they've demonstrated to me what they're doing, and they are very serious about that kind of thing.

You know, it's a rare thing to hear a General Manager sit with the Sales Manager and talk for some sustained period of time--a half-hour or forty minutes--about a brand new advertiser that just signed up that they want to get some results for. I mean, I did a survey one time and asked General Managers how often they participated in brainstorming for some kind of approach to a radio campaign for a brand new advertiser or an advertiser who is complaining that they're going to go off the air, and the answer was zero. They just won't do it. In my survey, however, I've learned since then that there are a number who are willing to do that. But the number is minuscule compared to what radio needs to do.

And the same thing with Sales Managers. Sales Managers will simply take the material and hand it to a Production Director, or if there is a copywriter at the station, give it to the copywriter. The copywriter will put it into a template they use for this sort of thing, and the result is that you get this kind of cloned radio advertising sound.

The issue has always been, is radio getting enough of the pie, and I don't think it is. It's not an accident that radio's national advertising revenues have dramatically fallen off. One of the reasons is that major advertisers are not persuaded that radio has the capacity to get the results. And they base it, not necessarily on campaign results, but on what they hear. Remember, every key advertising decision-maker may be a radio listener in a local community somewhere. He listens to advertising on his local radio station and says, "What crap that is. Boy, hope our advertising agency does better work than that." Then the agency, of course, says, "Yeah, well, radio really doesn't work that well. We're going to do television. We're going to do print for you." So it's not an accident that radio loses out on that, and I always have believed that if you want to change the way national advertising works, change the local advertising work because it will become a model and an inspiration for national radio decision-makers about the effectiveness of radio. They'll make their judgment on what they hear. And I can quote until I'm blue in the face all of the results from our clients, and we do when we talk to new national clients. But I know they are really basing their expectations of what we're going to do and what radio can do for them on what they have heard locally, and that's too bad. They just don't want to be associated with the medium, and that's not a grown up way for a major advertising medium to act. I've often wondered why there is this reluctance.

If you want an interesting book to read about advertising generally and in some cases radio, you should read "The Book of Gossage." It's a brand new book of essays and stories about a wonderful San Francisco advertising man called Howard Luck Gossage. He was very irascible. Remember the Beethoven T-shirts and all that kind of thing? Well, he invented that over twenty-five years ago. He died in the nineteen sixties, I think, and a lot of his fans and associates put this book together. In it, he is quoted as saying, "Nobody reads print ads. People read what interests them and sometimes it's a print ad." He was saying that to point out that it's an uphill battle in this matter of making advertising work. So, I sort of paraphrased that for radio and said, "Nobody listens to radio spots. People listen to what interests them and sometimes it's a radio spot." There's so much wisdom in this book. It's called "The Book of Gossage." It's in most book stores right now. It came out about nine months ago.

RAP: Laughter and joy seem to be the most common emotions evoked from the listeners in "Theater of the Mind" advertising. What about the other emotions like sadness or love or anger?

Dick: All available, all part of the arsenal available to radio writers and producers and performers. But it can only happen if you connect it to your own life experience. You can't manufacture it by dealing with the audience as something to be manipulated. As all good creative people have always understood--novelists, painters--you have to begin with your own life experience, and then you can connect.

Humor is not the only emotion available, but there's a practical issue here. You can't talk about tube socks, two for ninety-nine cents, by doing a very sad spot or a spot that calls upon the emotion of anger and all those things. But there are tons of extraordinary public service spots that have been done using emotions other than humor. One of my competitors, Chuck Blore, has done an extraordinary job with that for the people who wanted to reduce traffic deaths in Texas and get people to buckle up their seat belts. He did some wonderful spots that really played on our heartstrings about children involved in automobile accidents. So there are ways to do that. We do U.S. Health Care, which is an HMO on the east coast, and we often just do testimonials from people and definitely call upon emotions other than humor.

Radio can do it. The problem is that leader products such as snack products and potato chips don't lend themselves necessarily to something other than humor. That's why there's so much humor. Also, the fact of the matter is, today's post-modern sound is playfulness. I mean, we want to say to the audience that we know we're doing a commercial, and you know we're doing a commercial, so let's have some fun with this. That playfulness is part of the advertising sense. It's sort of the spirit of our times. Look at the milk spots, the Budweiser spots for radio and television. It's about playfulness. It's about saying, we know this is a commercial and you know this is a commercial, so let's all have fun in the context of that understanding between us.

RAP: When do you know you have a good spot, even though it hasn't hit the air yet, hasn't been tested or heard by the audience?

Dick: It's a good spot if it reaches you in some way and makes an impression on you, and after hearing it you can say, "It called attention to the product or service. I remember what it said. It set it apart from other products or services and it leaves me with a feeling that I like the people who make this product or service." That's not unimportant--"I like the people who make it. They have a sense of humor. They can make contact with the human condition. I like these people." Likability is a major factor in modern advertising or post-modern advertising. So, if you have all of those things working for it and it's not just about words, it's a good spot. If it appeals to you intellectually only and just gives you information, you may want to look at the spot again. If, on the other hand, it affects you in some kind of positive or emotional way, if after you've laughed you have some memorable sense of the position of the product vis-a-vis other products and services, the spot probably has worked for you.

RAP: What advice would you give programmers who want to get more quality creative work out of their Production Directors and production people?

Dick: Give them the opportunity to take more risks. You've got to be a little uncomfortable. I think there's a tendency sometimes to think you can take--Garrison Keillor called them dumb shits in a barroom--and put them on the air and expect that to work, although we do have our share here in Los Angeles. I do think you need to find somebody who has some kind of life experience, emotional maturity and opinions--not dumb shit in a barroom opinions, but something that works. All creativity, whether it's programming or commercials, is about risk taking and somebody in management having the capacity to stand the heat during that time and recognizing that failure is a part of growing, a part of the process. People have to fail in order to get from point A to point B.