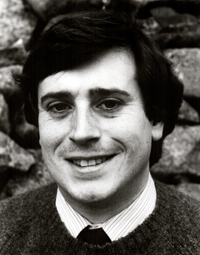

Alan R. Peterson, Production Director, WLAD-AM/WDAQ-FM, Danbury, CT

by Jerry Vigil

by Jerry Vigil

Is success found only in the major markets? Not at all. Join us as we check in with Al Peterson, author of Radio World's "From The Trenches," award winning commercial producer, air talent, synthesist, actor, juggler, cartoonist, razor rat, and all around good guy reporting from the trenches in small market U.S.A., Danbury, Connecticut.

R.A.P.: How did you get into radio?

Al: I was five when my dad brought a tape recorder home. I got hooked right away. Anything that could capture sound and spit it back at you right away was pretty heavy stuff for a five year old. By the time I was eight, I was able to splice only because I kept snapping the tape by jumping from play to rewind way too fast. In my early teens I was beginning to try sound-on-sound things like Les Paul did. He was one of my inspirations. In fact, he and I exchanged correspondence about a dozen or so times. I wrote to him, and he wrote to me with some very handy information. Anyway, by the time I hit college, I was a music major, concentrating on guitar and synth programming. I thought I was going to be this killer musician, but it never happened because I was tripping over better musicians starving in the street. Anyway, the college had an FM station, and I started there. I came in already knowing the gear. Up until then, I had been doing production, but I never knew it had a name.

R.A.P.: Where did you go after college?

Al: After graduation, I had a short stint with a music merchandising company, Sam Ashe in New York. Then it was off to Oswego, New York for my first professional job at WSGO, a one-kilowatt daytimer. My first month there I was a weekender on the air and did sales. I was a horrendous salesperson because it was one of those "here's the rate card; hit the street" things. There was no training or anything like that. Even to this day, I can fully appreciate what those guys do when they beat the bushes, but I just couldn't do it. Eventually, the night guy and I switched. I went to nights, and he went to sales. At that point I started getting more into the production and on-air aspect.

R.A.P.: How did you wind up in Danbury?

Al: I got married to my former wife just before she finished college. She got a job in Massachusetts near Springfield, and we moved out there. I started banging on doors and wound up at a couple of stations in Springfield, Northampton, and Great Barrington, Massachusetts. I pulled in two ad awards when I was in Springfield, the Western Mass Ad Club Award, for a couple of really crazy spots.

Northampton was cool because I worked four years for Cousin Brucie Morrow. He was a gas. His energy level was impossible to keep up with. I was PD and morning man for him during that time at WHMP-FM.

Then I went to Syracuse where I had an abortive year. I went out there, fell on my ass after eleven months, and kind of regrouped and came back to Massachusetts for a short stay at WSBS/WBBS. Around that time I was going through a divorce, too. So, after Massachusetts, I set out on my own and wound up in Danbury, Connecticut. That's where I've been ever since. I started in March of 1990.

R.A.P.: Tell us a little about the Danbury market?

Al: Danbury is ranked number 182, but, our proximity to other markets means we've got to stay on our toes. We've got to stay competitive. In Danbury, signals bomb in from Bridgeport, Connecticut; New York City; New Haven and a little bit from Hartford. So, my AM is up against stations like WFAN and some other heavy hitters. We're getting hit from all sides, but we hold our own. Our FM is either number one or tied for number one every time, and our AM comes in as the top AM in town.

R.A.P.: Too often, small market stations are merely stepping stones for young jocks. Are you working with other seasoned pros like yourself?

Al: Very much so. The morning man, Pete Summers, has been here six or seven years. Our Sports Director, Bart Bosterna, has been at it for about ten or eleven years at the same station. The AM staff has pretty much been in place for a while. I've been at it for two years, but those two have been anchoring the station for a long time.

R.A.P.: Did you start at WLAD/WDAQ as Production Director?

Al: No. I originally came here to do afternoon drive. Three days after I got here, the Production Director quit. I was right in the line of fire when the boss said, "We need a new Production Director," I walked by, "and you're it!"

R.A.P.: Are you doing an air shift?

Al: Yes. I'm on the AM middays from nine till one. As you can imagine, that cuts into a lot of production time, but I don't have to handle any writing duties. When I got here, I inherited a system which has been in place for a little while. Writing is done by Benmar, the fax service. You just send them information by fax, whatever it is the client wants. Then you check the box that says, "funny," "serious," "dramatic" or whatever, and a few minutes later they send back a piece of copy. It saves us time, and it saves us the cost of a copywriter. Plus, the salespeople are out beating the bushes, where they should be, and generally, the product that hits the air is very good. We'll have to tweak the copy from time to time just so we can be more specific; a lot of times what comes back from Benmar are just generalities. But more often than not, they hit the mark very well.

R.A.P.: You obviously have the talent to be working in a multi-track studio, but you're in a 2-track room. Is it for financial reasons that the station doesn't have a multi-track room?

Al: I don't believe that's the case. It's just that this has been the norm here for a very long time. I'd love to have it bumped up to four or 8-track, but at this point, number one, I don't think the amount of business we're doing would be able to support that. Number two, everyone's comfortable with doing 2-track work. It's equipment versus learning curve for a lot of people. I've been lucky because I can take to a piece of gear almost immediately. Part of my studies with music was synthesizer programming. So, if I run into something with a ton of knobs and faders, twenty minutes later I'm okay at it. But that's not necessarily so for most folks here.

Also, we only have one production studio at the moment, but we're rebuilding another one. So, we have limited time in production, and we all have a production shift, except for Pete and Bart. It gets cramped, and we have to rush through production. We've got to keep it somewhat simple. So, our gear is strictly straight 2-track.

R.A.P.: Judging from some of the work you've sent in for The Cassette, the lack of multi-track doesn't seem to hamper the quality of work coming from there very much.

Al: You learn to adapt. A long time ago -- in fact, it might have been in a back issue of Radio And Production - someone said, "If you can do it on 2-track, you can do it on anything." We've got some super blades here, some good razor rats. We also have a triple-decker cart playback deck. So, if we need to fly in bursts or sound effects or something, we have it right in front of us. It's the poor man's multi-tracking, yea, but that's the way we're doing it.

R.A.P.: What do you have for effects in the studio?

Al: When I got here, we had nothing. Tape echo was still the norm, and not just for us. It was other places around here, too. I happened to hear it and said, "No, this just won't do." So, on one of my trips back to my ex's place, to get more of my stuff, I brought back my little Alesis MidiVerb. I did a quick, jerry-rigged jack into the board and put an effect on one spot, and everybody said, "How did you do that?" I thought, "Man! There's a lot I've got to tell you guys!" Now, the SPX-90 we have in our studio is my own from home. It's loaded with a bunch of my own programs, some that were published in RAP, and a lot of people here are comfortable with using it. There are some new units on the market which we're still trying to decide upon.

R.A.P.: You mentioned that a second studio is being built. What's the scoop on that?

Al: We gutted one conference room to make way for a new AM studio, and we just dropped twenty-five grand on a new AM console. The old AM studio is going to be brought up to spec a little bit as a production room. In fact, right now, in Radio World, I'm doing a series of three articles on how our new studio is being put together. I'm not approaching how the production room will be done, but how the new AM studio is being done.

R.A.P.: One 2-track production studio is possibly the most common production setup among the country's 10,000 plus stations. What advice can you offer our many readers in ungarnished 2-track rooms?

Al: Every year, for the past two years now, I've done a production seminar for the IBS, the Intercollegiate Broadcasters -- college radio. They have a convention each year in New York. I head up the production "forum," so to speak. I was on one or two panels with some really good production guys from New York City. They would talk about digital editing and that sort of thing, but I was the one still coming from the 2-track direction. And I knew that was what a lot of the college people were still working on, too. My best advice for them and for anybody is this: the toys matter to some extent, but, my favorite production device, my favorite tool in the production room weighs about six pounds and fits between your ears. It's your brain. Some of the greatest ideas don't require any toys. If you can hear them in your head, and it takes effort, you can make them come across and come across brilliantly. So, don't depend too much on the toys. Use them as tools, but try not to build your entire piece just on an effect.

And we've heard that, too -- any of the old nitro burning, methane funny car spots. Those spots depend a lot on pitch shifting and tons of echo; and, if you were to take that away, the spot wouldn't have that much impact. But the minute you try to apply something like that to a furniture store, you're lost. It can't be done. That's where creative writing and better interpretation of the copy come in. That's very important.

I'm lucky to be close enough to New York City to take advantage of some free seminars. I read Back Stage, the actors' newspaper, and sometimes I'll read about how so and so is having a free, one-day voice-over seminar. It's not the whole class but more like a little teaser to get you involved in the class. I'll usually take the train down to New York, and I'll sit in on that free class just to get whatever information I can on how the big boys in New York are doing it, not for radio but for voice-over work that actors will be involved in. For me, that gives me the edge over the other guys in this market because I can interpret copy. Everybody else will "announce" it. We've got a couple of stations in this area that, no matter what comes through, it's going to sound "announced." It's going to sound, "car dealer." We have a place nearby called S&M Electric. They sent out a piece of copy one time which was so wonderful to play with. It talked about "faceted crystals playing shimmering light all around the room," and that kind of thing -- a spot for chandeliers. The copy was magic, until it was read with that announcer delivery. It was just so wooden and so stilted. Interpretation of the copy -- very important.

For anybody who's doing what I'm doing in a small, 2-track room, the best thing you can do, besides not depend on the toys, is spend one month or so with the local theatre company in your town. Those guys will really help you figure out what the words are all about. Do one play with these people, in the evenings. It'll kill your social life, temporarily, but you'll approach your copy from a whole different direction. I never took acting in college, but I wish I had. Everything I did was music, and whatever other courses went with it. But right after I got out of school, I began playing around with theatrics, and it really did help me, even when I was doing news.

R.A.P.: Good audio processing gear is very inexpensive these days, yet many stations still don't even have reverb. Any thoughts on this?

Al: A while back, I coined an acronym, "NICORI." That stands for "Nobody Is Capable Of Running It." That's been a big bugaboo for a lot of these electronic devices not turning up in radio stations. Someone takes a look at an intimidating panel and says, "What is this? All you need is bass and treble. You don't need all this crap! No, we're not getting it!" Instant prejudice because it's assumed instantly that no one is going to know what the hell it does. That's where NICORI came from. That's one of the more dangerous reasons why a lot of these places don't have gear like that. It's like, "What's this display for?" "What is REV, DIST, CHO? What does that mean? Reverb, Distortion, Chorus? We don't need that! Tape echo. Let's go with tape echo!"

I read something just yesterday which blew me away, talking about the cost curve for computers. In 1946, when Eniac, one of the first computers, was built, it was thirty tons and took up fifteen thousand square feet. What it used to be able to do has been surpassed a zillion times by a chip that can fit on your thumbnail. Now, logically extend that to the manufacturers of cars. If that same curve applied, you could buy a Rolls Royce today for $2.70, and it would get two-million miles to a gallon. The miniaturization, the improvements are happening all over the place, and the time has long been ripe for them to be in radio, even small 2-track studios.

R.A.P.: What would you say is your specialty in production?

Al: It's probably my approach to humor. If I'm writing something, the most dangerous thing they could do downstairs in sales is to write on a production order, "Feel free to produce as you see fit." That is the scariest thing they can do because when they drop something in my lap, invariably, the results come close to lunacy. We just did a spot for Brookfield Texaco, a little Texaco station up the street. It's a self-service station, but they were going to convert one of their islands back to full-service. The ideas kicked around in the sales department were, "Okay, let's have an unveiling." "No, let's have the pump stripping to show something new." I said, "Wait a minute! You said, 'island!' Let's do a Gilligan's Island knock-off!" I went home and synthesized the score, brought it in, had everybody pile into the studio and sing the jingle with new words, and all of a sudden, here's Skipper, the professor, and everybody else at a full-service island at a gas station. The client loved it! The client went nuts! "How did you come up with that?" It's just one of those things that falls in place. When something humorous comes along, it will usually present itself very, very obviously. It'll almost clobber you over the head. If that's the feeling, if that's the gut impression you get, run with it the second it hits you. Go with it.

So, for me, even though I don't do too much writing, when they hand it my way, that's very strong for me. Plus, we have the expertise here among all the producers to be able to pull it off.

R.A.P.: When you speak of "the producers" you're referring to the jocks. How many of them are producing on a regular basis?

Al: A total of about five -- the FM jocks, and occasionally, one or two of the AM guys will get into play as well. The morning man on the FM, Bill Trotta, has a good head for production. In fact, I think he was Production Director at WGSM, where Flip Michaels is now. He's got a production head and knows what does and doesn't work. We have one young guy in the nighttime, Ryan Carrington. We hold on to him for the flamethrower, nightclub kind of spots. He's about ten years younger than most of us, and he still has that edge in his voice that works. As far as the AM personnel go, I'm the only one, from the AM side, who does production.

R.A.P.: In a small market you must get your share of spots that the client wants to voice himself. How do you deal with those?

Al: We're able to have a lot of fun with our client spots. You know what it's like when clients voice spots. Many times, it's like death. A lot of times, they're not going to be terribly exciting. Take Dennis Jenovski, a guy who runs a gem store locally. He knows he's not a top voice talent by any means. But he comes in with his own copy ideas, and they're brilliant. So, he just drops his voice into a sketch type spot, and he behaves just like the anchor, the pivot to keep the spot running away. For me, working with clients gets tough, but as long as they don't voice the whole spot, there's something to be said for it. They can be used successfully. You've just got to know how to frame them right.

Recalling something else I wrote for Radio World, I did an article called, "Ay, You 'Ungry?" It was about a restaurant owner who had rejected every possible idea we had for a commercial. Something he said off the cuff one day became the slogan he went with for about a year. For him, it was a "client voiced" spot, but that was the only thing he said in the commercial -- "Ay, you 'ungry? You better be 'ungry!" That's all he had to say, and he was an instant celebrity.

R.A.P.: How did you get started writing "From The Trenches" for Radio World?

Al: That was bizarre. I was always sending little clips to Judith Gross, the editor at the time. She used to work in upstate New York, and I always used to drop her little messages as to what was happening on the scene there. I guess she started to like some of the stuff I sent her. She sent me one of those little Radio World mugs. In early April of '89, they fired me from WHEN. I wrote her one last note saying, "It's going to be a while before you hear from me again. I've been fired...," and I began writing all that stuff that I'd always wanted to say about the paper and about a few other things. A couple of weeks later, I got back a 2-pager that said, "Al, we're starting a new column, and we'd like you to write it." So, out of no place came "From The Trenches." In fact, they came up with the title from one of the lines in my initial letter to her. It was a bolt out of the blue. There I was, suddenly out of work; then I had a column in a national publication.

It's basically just a look at the goofier side of life from my side of the station. There's enough engineering and management columns, programming strategies and things; but there's really nothing out there that says, "Boy, this part of life is sure damn funny!" Last time I saw something like that, Bobby Ocean was doing a cartoon strip for R&R about ten years ago. In July I'll be starting my fourth year of writing the column, and I've been enjoying it. There's an awful lot of "me too" out there, and I'm realizing just how universal the feelings are for a lot of people. Basically, my column is, "Hey, this is happening to me, too. Am I alone, or what? Does this goofy stuff only happen to me, or is it universal?"

The most mail I got was when I did a two-parter on dead-air dreams -- it's the middle of the night and you're dreaming you're at a radio station where nothing works and there are no records left.

R.A.P.: Radio World offers free subscriptions to people in radio. Do you have their address handy for any of our readers that would like to start reading your column?

Al: Write to Radio World at P.O. Box 1214, Fall Church, VA 22041. I'm in every other issue. There's more to it, obviously, than my column. But my column is for anyone that has had that feeling of what it's really like at "our end of the building."

R.A.P.: Radio World is more of an engineering publication, and you write a lot about that aspect of the industry as well. How can we as production people better deal with our engineers?

Al: Get on a level with them. You don't have to study up on electronics just to try and dazzle them, but if they try and dazzle you, it's always good to be ready with something because they can come up and talk about the framostat and the widget being ninety degrees out of phase which means your fluminator is going to...you know, all the nonsense. Anticipate that and just learn a little something about what's happening. Understand that if you switch your speakers to mono why suddenly a phasing problem on tape suddenly makes your cart sound like it's honking. Understand why that's happening, and try and talk their language a little. If you can go in there and say more than just, "Tom, the cart machine sounds funny," if you can leave him a note that says, "I'm hearing a grinding noise from what might be the bearing," or, "I'm smelling something hot. Is it the erase coil?" If you can talk in ways that won't make him go looking for the rest of his life for something, it'll be a big help.

One of the more brilliant people I worked with was Roy Taylor in Syracuse at WHEN. This guy would stop and explain everything to you and make it simple, make it understandable. He wouldn't talk about why the VCO isn't doing what it should; but, he'll say, "Oh, it's because...," and he'll make it absolutely, brilliantly simple.

Just understand engineers. There are a lot of them that are very, very good. Some of them still treat their position as extremely lofty, and that's okay. There are a lot of production people I know, and sometimes I even get in the habit myself of feeling like I'm the only one in the industry that knows what the hell I'm doing. Well, I'm not! Obviously, I'm not. I read up on what other people are doing, and I'm amazed at some of the stuff being done. Since you're working as a team, understand what it takes to work as a team. Get on the same level as your engineer. You don't need the SBE certification, just use your head. You've got to have a technical mind to even be in that studio. Work with it a little more, and work with him or her. There are a lot of "her" engineers out there.

You will occasionally come across an old-timer, who in my book is the engineer who thinks production should be, "put the Montovani record on and start talking, and if you need an effect, here's tape echo. Have fun." You'll run into these guys occasionally. Well, these are the guys you just look at and smile. Then, late at night, you bring in your own effect box and patch it in just like I did. And don't tell anybody. He wasn't thrilled with me, of course, but eventually, he got around to wiring my own box in.

R.A.P.: What production libraries are you using?

Al: A couple of years ago, we were doing without a production library. We basically did just what other stations do -- "borrow" stuff off of jazz albums and Windham Hill records and hope no one's the wiser. But, after a while, you run out of flexibility doing that. So, at Radio '90 in Boston, along came TM Century's three for one buyout. I said to my boss, "this is what we should have." He said, "Okay, it's yours." So, we got it. We got Trendsetter, Lazer, and the Century 21 collection. All told, they're very good libraries, and they send me updates every now and again which is always fun.

Our FM is a hot AC, and we don't really need lazer bursts and a lot of hairy, crazy things. What we do is upbeat, yea, but not to the point of sounding like real flamethrowing CHR. So, the collections we have are perfectly appropriate for our needs.

R.A.P.: Did you get a sound effects library with the deal?

Al: Yes. We got a sound effects package from TM, but, honestly, it sounds like some of the stuff got transferred directly from vinyl disk onto CD because I do hear some pops and ticks. What we've been doing for some sound effects is running out in the field and just getting our own as we need them. A lot of times we'll need party horns for celebrations, New Year's and that kind of thing. I can't find these horns anywhere on our sound effects library. So, we blew $1.49 on ten party horns and stood around blowing them around a mike. When in doubt...do it yourself.

R.A.P.: Tell us a little more about your musical background and how you're using it in production.

Al: Well, I'm starting to think twice about it and about some of the music I have been using because of all the copyright articles that have been showing up in RAP. It seems everybody is taking a second look at it. And, frankly, there's going to be some clients that say, "Listen. I'm not going to do this commercial if I don't have 'Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairies' on the spot. I want that on the spot." Some guys you're just not going to talk out of using a certain piece of music. So, sometimes, that's when I bring out the big guns. Out comes the gear, and we'll attempt to simulate the song or come as close as we can to it. It might take an extra day or two because the station's not set up for synthesis, but my living room sure is. Very rarely do I do song parodies -- we subscribe to enough comedy services that provide us with that kind of thing - but once in a while something will come along like the Gilligan's spot.

R.A.P.: Not to be difficult, but by performing Gilligan's theme yourself, don't you only avoid illegal use of someone else's performance? What about the composer of the song? Isn't there still something to consider there?

Al: I'm sure there is, yes. But....

R.A.P.: Hey, you only ripped it off half as badly as most people would!

Al: (laughs) Let me put it this way: I've heard enough Star Trek knock-offs with the Star Trek theme to say, "Okay, how come nobody is paying anything to Gene Roddenberry's Estate?" It's not legal, I know; but there's a gray line there.... Everybody knows Gilligan's Island, and, for some reason, it seems almost okay to adapt it. I know I'll probably get in a whole lot of trouble for saying that, but Gilligan's Island was a part of growing up. It was a part of your life. In a way, that doesn't make it okay to steal it, but it softens the blow just a little bit. I'm not doing a good job of defending myself, I know, but that's the defense I came up with over here, that it's recognized as an icon, and everybody would know it right away.

R.A.P.: "Borrowing" music from an album of classic TV themes is something that has been a part of radio production forever. There really should be some way radio stations can legally use this music for local broadcast.

Al: Yes. And you've got to wonder about that Star Trek sound effects CD that's out. Now, you're not going to take that home and listen to it for pleasure. The people who made that CD know you're going to use it for something. You're going to plug it into a high school play, or a video production, or something.

Talking about effects CDs, here's something I'd love to see someday. I wrote to the Columbia people about this. I asked them if they'd ever consider issuing the Three Stooges sound effects on CD. Nothing would make me happier than to have the Stooges head clank, the coconut head bonk, and all that other stuff on a CD or loaded into a sampler. That would be funny as hell. And again, using these sounds goes beyond talking about performance rights. The Stooges are an icon. They're something everybody knows. The minute you hear, "Boink! Bonk!" and all that stuff, you know who it is. Again, the estate would have a tough time with that, but, it has gotten to the point where something like that should really be available. How, legally, I don't know, but it would be nice if it was.

R.A.P.: Are you producing any original music for commercials and promos?

Al: Nothing right now for spots and promos, but I am scoring a planetarium show right now. Some of the textures that are in the synthesizers I own are very nice sounding and lend themselves to outer space kind of stuff.

R.A.P.: Do you have a pretty nice studio at home?

Al: Well, the gear is nice. The cabinetry I had to put together myself because everything commercially available was fairly expensive. It's your basic rat's nest of wiring, but the instrumentation is pretty nice. The main keyboard is the Roland D-50. There's the Roland Sound Canvas module. I have the Yamaha TG-33 which is a great little synth. There are a couple of drum boxes. I've got the Alesis sequencer, the little MMT8, and a MIDI disk recorder, the cheap Brother unit. I use that to save my stuff on. The rest of the audio gear is Tascam and Teac. I've got the Tascam Syncassette, the 4-track rack-mount cassette. My reel-to-reel is the Tascam 222. And it all goes through a little Teac 2A, a six in, four out board with no meters.

The best equipped room I ever worked in was when I was at WHEN in Syracuse. Their studio was a mono studio using Scully gear, but they had every toy I could have wanted. They had a Harmonizer. A Mini-Moog was there. They had an Ensoniq sampler, reverb, and graphic EQ. I was turning out what I thought was some fun work there. Tom Saywer is now the production man there, and he's been there since I left in '89. He's having all the fun, I'm sure.

R.A.P.: Does your station use any outside voices for Ids and such?

Al: Yes, we use Brian James. He'll send us a finished voice tape, compressed and EQ'd the way only he can do it. Sometimes we'll produce his stuff here. Other times he'll add a laser or two and we'll add to that. He also has a sampler down there, and I was surprised to find out it was the Roland S-10. It's a really simple keyboard sampler, but that guy can make it jump through fiery hoops. The stuff he does is great. Despite how good of an "attitude" liner guy he is, he can soften up when he wants to, and he had to for our station. When he pulls back a bit, he sounds more friendly and homey than he does when he's "in your face!" He really surprised me with how versatile he is.

For our AM station, John Young out of Atlanta is our liner guy. He just sends us raw voice only. We take care of all the fun stuff here.

R.A.P.: How has the economy affected the stations?

Al: We just had our best May ever. Everybody picked up a bonus for breaking records here. I was very, very happy about that. It meant a lot of work for my department, but we still came through okay, and the big boss man decided to share the wealth. As far as being an AM in this area goes, in Danbury, AM is still very much alive. And can I say the Production Department is leading the charge? Probably not, but we're helping make it happen.

R.A.P.: Your stations sound quite special. Have either of them won any awards for station of the year or anything like that?

Al: Our news department grabs UPI awards every single year. They've received Connecticut Broadcasters awards, and others. The news department here is second to none. Every time a disaster happens locally, one of the first projects I have to do is put together a promo. "WLAD News was there, first on the scene."

We just had a guy crash a homemade plane into a duck pond just the other day. He walked away from it, but he was kind of embarrassed. There was another guy in the plane with him, and they both walked away from it. We had a live reporter there taking feeds, and within a half hour, a promo was cut for it and was running for the rest of the week.

We started a contest and created a character some months back called the WLAD Daredevil. This character is nothing more than a man's scream off one of the TM sound effects disks. We usually put the WLAD Daredevil into some icky situation, like going over the falls in a barrel for a Niagara Falls vacation trip. When we gave away circus tickets, we through the Daredevil in a lion's cage. We do things like that with the character, and the promo always ends with this guy screaming. Well, to add insult to injury, after the plane incident, we had him fly a plane into a duck pond, using all the sound effects from TM, Hollywood Edge, and a few other collections, and the result was pretty funny. Even the pilot called us up asking for a copy. As embarrassed as he was, he thought it was hysterical -- either that, or he's taking us to court.

R.A.P.: How many spots would you say your department is cranking out each day for both stations?

Al: I'd say up to nine or so pieces of copy per day. We have a lot of agency stuff come in, too. A lot of the spots we do are more than just cut and dry kind of production. They involve music changes, a lot of special effects, a lot of voices. So, despite the low number of spots per day, the work is there.

After the afternoon guy gets finished with his production, I go back in at the end of the day. When the new studio is up and running, then I'll be able to devote more time to specs and updating promos and things that are necessary. Again, the airshift gets in the way, but when you're dealing with a small shop, that's part of the deal.

R.A.P.: What would you like to see happen at your station regarding production?

Al: Something I'd like to see, not just here, but anywhere, is just what any Production Director would ask for, something other than that "4:59 in the afternoon, quick, I need this by yesterday" syndrome. I have one salesperson over here that jokes about it. One time he sent me three projects in a row which were last second, and ever since then, he's been coming over to me at the end of the day saying, "quick, I need a five-voicer and a Swedish dialect."

If anything, I'd like to see just a reasonable idea around all departments that there is such a thing, as newspapers will tell you, as a deadline. If a newspaper says ad copy has to be in by ten o'clock, and the copy comes in at 10:15, it ain't going. So, show me a staff with a reasonable concept of what that's all about. Again, I know how tough it is to sell, and I'm not belittling their efforts, but when you're a team, you've got to work as such. I know there's always going to be exceptions to the rule, and that's part of the job. I accept that, as anybody else who does what I do should. But, when it gets to the point of being abused, then it gets to be a hassle and the amusing aspect of it stops.

R.A.P.: How do you deal with the last minute production orders you do get?

Al: Fortunately, I've got an evening guy on the FM who enjoys doing production and does a good job of it. A lot of times, I'll hand it off to him. Sometimes I'll have no choice but to do it myself. Other times it goes back to the salesperson with me saying, "Look, I know this is important, but, number one, you know it's a minute before five. You know what's involved on this, and it just can't be done tonight. I'm very sorry." I'll get my ear chewed a little bit, but some things just can't be done at that hour. And it's not because I'm anxious to get out of there; it's because the resources I need may not be inhouse.

Obviously, it's very nice to have money coming into the station. If it means having to kick around an extra few minutes at the end of the day, I'll just swallow the pride and get the job done. But, I want to be able to do a good job, too. It's not just about me and my inconvenience. It's the fact that, yea, this guy took the time and money to advertise on us instead of them; so let's show him we can really pull out the stops. And again, because of the saturation of signals from other markets, we can't just give them your basic "warm, friendly, and casual atmosphere" kind of spot. We can't do the "conveniently located" kind of spot. The clients have come to expect a lot more than that because they're hearing stuff out of the bigger cities, and they know that your basic, "what a wide selection of wide variety," won't work.

And it's not just the signals from other markets that makes us put more emphasis on production. I wouldn't have it any other way. I put a lot of pride into what I've done up to now, and small market or big, I still want to do the best job I can. Plus, it's fun to make the other guys up the street wonder, "How the hell did he do that," especially when I drag in a synthesizer thing I did at home.

R.A.P.: Do you have any requests for our readers?

Al: I'd like to see some of the big guns, some of the guys who do their own sweepers, synth bursts, and things like that, I would love just once to have somebody publish in RAP for the benefit of the tiny number of us that actually have synthesizers, just publish one of their patches. Show us how the heck you guys do that. Tell me what gear you're patching together. It doesn't have to be elaborate, and I know it addresses just a very tiny percentage of people that have that kind of gear to fool around with. I know it's their sound, and they're the ones making money from it, but they invented ninety different sounds. What harm can giving up one do?

R.A.P.: Any parting thoughts for our readers in the smaller markets?

Al: Like anybody else, you're always going to want the bigger tape deck, more memory in the sampler. You're always going to want something extra. I'm trying to do that on my own. For example, I'm just starting to learn digital computer recording and editing, but I'm doing it at home. I don't own my rig yet, but I'm starting to understand it now and work with somebody else's. This way, if we ever do go that direction, the learning curve for everybody else won't be hysterical because I will already know how it's done. This way, I can make my mistakes in the stupidity of my own home, as I once said in Radio World.

So, learn as much as you can on your own. Visit the music store as much as you can. See what's being done at other stations. If you're vacationing, call ahead to a big station and say, "Hey, listen. My name is so and so. Can I just look for nine or ten minutes? I'll be out of there before you know it." Give that a try. And, as Dan O'Day likes to say, "Never be satisfied with your work. Next time around, you'll have a better spot waiting for you."

♦