by Steve Cunningham

Lately I seem to be surrounded by hard drive failures. It started a couple of months ago when a client, whose production machines I maintain, called to report that one machine had locked up. When he tried to reboot it, the hard drive made grinding noises and refused to boot. Two weeks later another client called reporting that two external backup drives from the same manufacturer just refused to spin up. Then there were the two laptop drives that failed, each of which issued clicking sounds instead of spinning up.

In all cases, the hard drives involved were simply toast. No amount of software diagnostics, recovery tools, or voodoo rituals worked, and I tried ‘em all. This included my favorite trick which consists of putting the dying drive in a sealed baggie and then into the freezer for 30 minutes, in an effort to get the spindle bearings to shrink up for long enough to get the data off the drive. That didn’t work either.

In the case of my laptop drives, I had a current backup of all the data on both of them. There was some damage to my schedule as I worked to restore data on the two of them, but since I had a proper backup the only thing I really lost was the time involved restoring the data. I wish I could say the same for my clients’ drives, but I cannot. Each lost a substantial amount of unrecoverable data, a situation made even sadder given the fact that the data loss was preventable.

It seemed to me that our last discussion of backup strategies was a long time ago. I couldn’t remember how long, but I had a feeling it happened quite awhile ago. So I looked it up. The last time I wrote in RAP about backing stuff up was in the August 2003 issue, or almost exactly seven years ago. You may find this hard to believe, but I still have most of the important digital files today that I had in 2003, and in at least one case, much longer than that.

You see, I’m a pack rat with digital files. I actually have a text file of an email from a friend, in which he congratulated me on the birth of my son. That boy just celebrated his 24th birthday, so you can do the math... or not, never mind, it was 1986. And it wasn’t an email like you and I have email today; rather it was a text copy of a forum message from one of the original audio-oriented Bulletin Board Systems out there. Those of you who remember the BBS are seriously dating yourselves right about now. No, really, if you remember that you’re old. Sorry but it’s true, and I know it’s true because I was there and I have the text file to prove it. Dated June 1, 1986, and I’m not kidding. Came to me over a dial-up modem that rendered my home phone unusable, quite possibly at 300 baud, or maybe 1200. Yeah, so I have that, and I have it backed up for a fare-thee-well, because it matters to me. So do a lot of other client files I’ve created over the years.

“Pish-tosh on your backup,” you may say. “I’ve got a couple of one-point-five-terabyte (1.5TB) drives and they’re new and trouble-free, so I don’t need to be paranoid about backups.” Okay, perhaps you don’t, but what’s going to backup your backup? And how will you backup an entire 1.5TB hard drive anyway? If you have all your backed up material stored on one of these massive drives, then you’re doing just fine, right up to the point when that drive fails, which eventually it will do. And tape backup is quite nearly dead, isn’t it? I certainly think so, given the few vendors still making the cartridges.

IS QUALITY STILL JOB ONE?

IS QUALITY STILL JOB ONE?

The problem is that while drive capacity has increased, it appears to me that drive reliability has actually decreased from what it was a decade ago. I admit that I am working from my own anecdotal evidence, but here’s what I’ve noticed.

Seven or eight years ago, the most popular hard drive size was around 80GB, and I still have over a dozen drives with that capacity that are still in service and show no signs of failure, mechanically or electrically. However, drives that I’ve purchased for personal or business use in the past three or four years, while much larger, are now beginning to exhibit signs of upcoming failure, either via their S.M.A.R.T status (aka SMART which stands for Self-Monitoring, Analysis, and Reporting Technology), or by dint of their increased noise production.

It is worth noting that Google proved that the so-called SMART status really isn’t, when they performed a large scale drive survey in 2007. Google studied a hundred thousand SATA and PATA drives with between 80 and 400GB storage and 5400 to 7200rpm, and while unfortunately they didn’t call out specific brands or models that had high failure rates, they did find a few interesting patterns in failing hard drives. One of those I thought most intriguing was that drives often needed replacement for issues that SMART drive status polling didn’t or couldn’t determine, and 56% of failed drives did not raise any significant SMART flags (and that’s interesting, of course, because SMART exists solely to survey hard drive health); other notable patterns showed that failure rates are indeed definitely correlated to drive manufacturer, model, and age; failure rates did not correspond to drive usage except in very young and old drives (i.e. heavy data “grinding” is not a significant factor in failure); and there is less correlation between drive temperature and failure rates than might have been expected, and drives that are cooled excessively actually fail more often than those running a little hot.

While the manufacturers’ MTBF (Mean Time Before Failure) numbers are increasing, the useful service life of a consumer-grade hard drive is now considered by experts 3 to 5 years. Note that the MTBF is an estimate from the manufacturer based on the performance of other models, while the service life tends to come from quantitative experience with drives that are in service in the field. It may be telling that several drive vendors have reduced the length of their warranty period; Seagate’s used to be a full five years on even their consumer drives, but it is now three years for the newest models.

Manufacturing missteps on the part of several hard drive manufacturers which caused drives to fail prematurely have added to customer concerns over decreasing service life. Simply checking out customer ratings for hard drives on vendors’ websites reveals a decline in quality and an increase in infant mortality -- hard drives that die within 30 days of use -- along with more negative comments and ratings from those who bought troubled drives.

So one can now safely assume that a newly-purchased large hard drive may fail some time after three years of service, down from five years (by my experience). There is also a very slight possibility that it may succumb to infant mortality (although if it’s your drive that fails in 30 days, you don’t really care how slight the chances were, do you?).

AN ESSENTIAL INCONVENIENCE

Backup is more essential than ever, especially given the size of today’s hard drives. It’s actually becoming difficult to buy a hard drive of less that 300GB capacity. Most are 500GB and up, which means that losing an entire drive can mean losing a lot more content. Drive manufacturers continue to design larger drives, as prices of the previous and only slightly smaller drives continue to fall. Seagate, for example, has already announced 3TB drives that could be available late this year.

So how does one avoid data loss disaster while maintaining one’s sanity? I like and adhere to the 3-2-1 rule, a strategy developed by digital photographer Peter Krogh (the guy even wrote a book on it, available at amazon.com and entitled “The DAM Book: Digital Asset Management for Photographers”). Here’s how the 3-2-1 works: To be fully protected, you should have three copies of any file (that’s three different devices, not three copies on the same device), two different media types (like hard drive and recordable DVD, for instance), and one of the copies should be stored off-site. If you can adhere to this rule, your assets will be extremely well-protected.

Not too complex a scheme, is it? But it does work, and works as well with audio files as it does with photographs. As far as I’m concerned, digital data does not exist unless there are three copies of that original audio stored on two different types of media, in case one of these becomes obsolete, and one of the copies is off-campus, so to speak. The off-campus copy could well be an Internet-based backup system such as Carbonite <www.carbonite.com> or Mozy <www.mozy.com>.

ONLINE BACKUP

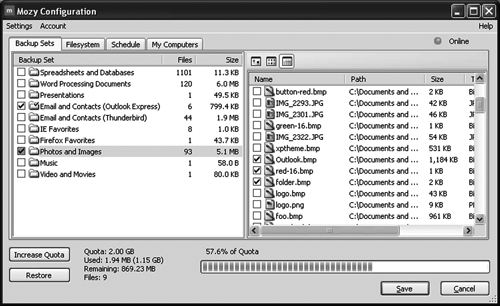

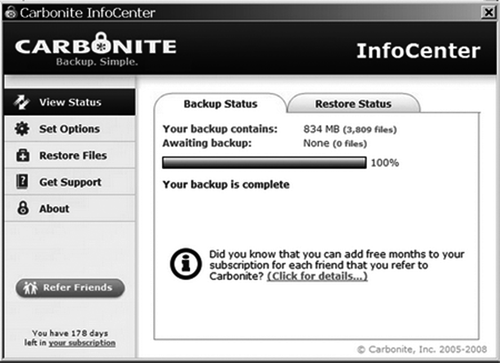

If you haven’t heard of either service, they’re quite simple. For four or five dollars per month, both Mozy and Carbonite provide you with unlimited online storage of backup files from your computer. By downloading and running a reasonably lightweight program in the background, both services backup your files onto company servers on the web. Depending on how much data you have and want to back up, the initial online process can take days, if not weeks.

My first go at Carbonite was via their 30 day free trial offer that’s advertised all over the radio and the web. I set it up to give me a backup of my entire boot drive, totalling 500GB. You can set preferences in Carbonite to determine how aggressive it is with your computer’s resources. Set to background it will only work when you’re not working, but set it to use more resources and you will in fact feel a drain on your computer’s performance as Carbonite works.

Despite using both settings, at the end of the 30-day trial Carbonite had backed up about 150GB of a total of 365GB of files... less than half. A phone call to support got me an extension on the 30-day offer and enough additional time to complete the initial backup. Subsequent backups have been quick and painless, and work fine on the least aggressive settings. Keep in mind that the speed of the backup, particularly the initial backup, is completely dependent upon the upload speed of your internet connection. Since most consumer-level Internet services provide fast download and much slower upload speeds, it makes sense that the backup is slow. While I haven’t yet done a full restore from the online backup, the partial restores have moved along at eight to ten times the speed of the backup. I estimate that doing a full restore using Carbonite will take a couple of days.

One unfortunate limitation of both these services is that they will only backup internal drives. At this time they will not backup external drives, even if those external drives are connected and mounted on your computer. They only work on drives that are connected directly to your motherboard.

Having said that, what’s on the boot drive is the most important part and the biggest pain when it goes down, so I feel Carbonite is still worth the five bucks a month I’m paying for it. And after all, this is only one of the three backups I have available, albeit the slowest one. My total backup solution includes two external hard drives, one of which stays home and the other that travels to my office. These two are rotated weekly, so should disaster strike in either place I cannot lose more than a week’s work, and that doesn’t include the online backup to fill in gaps.

THE RAID SOLUTION

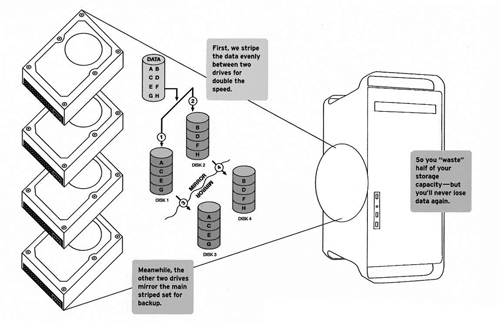

There is another partial solution to the problem of large hard drives becoming questionable, and that is to create from a number of them a RAID. By binding a couple of these large drives together in a RAID 1 configuration, you get the benefit of a large drive size and redundancy. RAID 1 writes the same data to each of two drives, all the time, so if one drive fails the other still has valid data on it. There’s no speed benefit in this configuration, but the peace of mind that comes with redundancy makes up for it quite well.

So when Seagate finally ships their 3TB drives, then I will go out and buy a couple of 1.5TB or 2TB drives (which should be cheaper by then), and I’ll mount them in a common external case an create a RAID. It’ll make one heck of a backup system. Besides, after writing this, having all those older 80GB drives around is now making me nervous.

♦