GETTING CONNECTED

In order to record remotely, you first need to register yourself as a Source-Connect user or studio on the company’s website. This website acts as a virtual guestbook, keeping track of who you’ve approved and who’s approved you as a partner. When you fire up the Source-Connect software plug, your partners will show in a list allowing you to choose which one you wish to connect to for recording. You’ll also need a broadband Internet connection of some flavor, and Source Elements advise that this needs to have download and upload speeds of at least 300kbps.

If you’re the talent and you’re using the Source Elements Desktop version, it doesn’t get much easier. Source Elements Desktop comes with the VST plug-in, whereby the Desktop program acts as a wrapper to host the VST plug-in. The entire business is very slick and very easy to use, much more so than using the plug as an insert in a digital editor.

Once you’ve downloaded and installed the VST plug and the Desktop application, double-clicking the program activates both. The first thing you’ll see is the Desktop applications main window. You’ll want to configure your audio I/O, which can consist of just about anything you can connect to your computer. This is particularly cool for working on the road, because the app does not discriminate against USB microphones or small USB interfaces from various manufacturers. Just because the main session is on a ProTools HD system doesn’t mean that you can’t use an inexpensive USB headset mic to do the voiceover from several hundred miles away. Clicking on the Source-Connect (or Source-Live) button brings up the actual plug-in. You’ll need access to the plug in order to connect to the remote studio from the list you created earlier on the website, right?

The next section, labeled Record, lets the talent record him or herself during a read. This is an important feature because Source-Connect often fixes glitches that may occur during transmission by replacing chunks of the performance in the background with clean, original audio from the talent’s recording. This is the secret of Source-Connect’s ability to deliver clean audio over the Internet. If the studio is using the Pro version it can, if necessary, actually replace entire tracks in the background after the session recording is done.

The lower half of the Desktop application comes with a mix window where you can adjust the relative levels of your microphone, the playback from the studio, and even a prerecorded file. At the bottom is a talkback function which, if it’s set up properly on the studio end, will make you swear you were in the booth rather than on the other side of the country.

How does it work if you’re engineering in the studio? The Source-Connect plug-in gets installed as an insert on an aux track, then you route the audio to and from that track so that, in effect, the aux track becomes your remote I/O interface. It is important to note that the Source-Connect plug-in does not act like other plug-ins, in that audio routed to the input of this channel no longer reaches its output when Source-Connect is inserted. Instead, audio routed to the input of the channel gets sent out over the Internet, and the audio received from the Internet shows up on the output of the aux track, so it must be bussed to an audio track for recording.

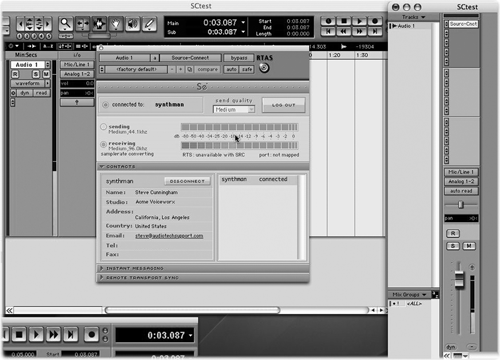

No matter which flavor of the product you’re using, the plug-in portion will provide you with information regarding your send and receive levels, a contact screen that allows you to connect and disconnect from your partner, and an instant message panel that provides real-time information as well as a place to chat with the studio.

THE SOURCE EXPERIENCE

THE SOURCE EXPERIENCE

Given the fact that most ISDN codecs use some form of compression on their audio, the Source-Connect products sound every bit as good as any Zephyr I’ve heard. In my evaluation of the plugs and the Desktop software, my partner and I did experience a bit of the same fiddley-ness than I’m used to experiencing with ISDN codecs. We did experience the odd dropped connection, but considering that both of us were using dynamic IP addresses I’m not surprised. The company specifically recommends that studios have static IP addresses to eliminate at least the one variable, but unfortunately we didn’t have that option available to us.

As far as I’m concerned, the most exciting thing about the source element products is the fact that I no longer have to counsel new voiceover talent as to whether or not they should purchase an expensive Zephyr codec, or whom at the phone company they might speak to about getting ever more rare ISDN lines installed in their studio.

Have you tried calling the phone company about an ISDN line lately?

The last time I did, a helpful company representative wanted to know why I would want such an old, slow connection for the Internet.

Best of all, Source Elements has reached what I consider to be critical mass in terms of the number of users of their product. There are Source-Connect studios in nearly 70 countries throughout the world, and thousands of voice talents working in and out of their homes are getting their job done using Source-Connect. It’s an idea whose time has come, and it is indeed time to pull the plug on those ISDN lines. Good riddance, and thanks for the extra $36 a month.

For more information worldwide, visit www.sourceelements.com to download a demo or purchase the product.

Sidebar: So Why Doesn’t Plain Old VOIP Work?

As most of you probably know, the Internet works in part because it is based on the theory of packets. All data is broken into packets (sometimes referred to as packetization) before being sent. Each packet carries the sender’s address and the receivers address, along with a serial number. In that way, each packet can take a completely different route to get from the sender to the receiver, and the included addresses and serial number allow the receiver to reassemble the packets into the original message. This concept is key to making Internet communications work, because if the packet is lost along the way the receiver can simply send a message back to the sender requesting that that packet be resent. We are not troubled by the fact that some packets arrive before others, because they’re all going to be reassembled in the end anyway.

Unfortunately this is bad news for high-quality digital audio. High-bitrate digital audio represents a whole lot of packets that must arrive on time and in order. There’s simply not enough time to request a replacement packet without creating a click, pop, or other unwanted noise. So how then do VOIP services like Skype manage to do it? First, Skype’s audio is highly compressed at variable rates, often as low as 32kbps in mono. Second, Skype takes advantage of the two different kinds of packets most often used on the Internet.

The first type of packet is what’s called a TCP packet. This packet contains all of the address information, along with a request for an acknowledgment from the receiver. Simply put, TCP packets ask the receiver to send a message back to the sender saying “yes I got it,” which confirms that a communication channel is open and established but also takes additional time. The second type of packet is called a UDP packet. This packet carries with it no such instruction for an acknowledgment from the sender. It’s simply a packet of data among millions of other packets of data.

So when you call using Skype, the initial conversation consists primarily of TCP packets that establish a channel of communication between you and the other party. Once you start chatting in earnest, the conversation consists mostly of UDP packets that require no acknowledgment. Every now and then Skype will send some TCP packets to ensure that the connection is still valid, but most of your conversation consists of UDP packets. If a few of those UDP packets are lost along the way, no great harm is done and you’ll simply hear a little additional noise or artifacts. These may be annoying, but they’re not a deal breaker when using Skype to call Aunt Tillie. But they will ruin a remote voiceover session.

Will a faster network connection help? Of course it will, but Internet connections seem lately to not be getting faster, but slower as more people connect to the same backbones. Combine that with the issue of Net Neutrality, and for most of us faster pipes are still awhile off.

♦