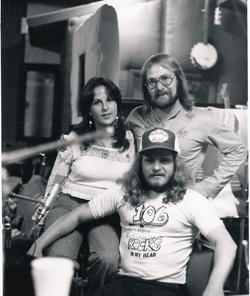

Steve Wein, Creative Services Director, KTRS-AM, St. Louis, Missouri

By Jerry Vigil

By Jerry Vigil

You’ve heard the advice… “find something you love doing, something you’re passionate about. The rest will fall into place.” Maybe you’re still waiting for those things to “fall into place,” but most likely, if you’re a regular reader of RAP, you’re passionate about what you do and love it, and for many of you, life is good, and there’s nothing else you’d rather be doing. For Steve Wein, it’s a passion and love that has treated him well for nearly 40 years. Coming from a family of broadcasters, it didn’t take Steve long to find his niche in the family business. Before long, Steve was out on his own, turning creative commercials into dollars and happy clients, and the journey hasn’t let up. Today, Steve cranks out the creative for the clients at KTRS-AM in St. Louis, the only station owned by CH Holdings. Currently #4, and within a ½ point of being the #2 station in the market, KTRS is one of those rare instances of a privately owned station in a large market that leaves the majority of the major group-owned stations in its dust. In this month’s RAP Interview, Steve shares some interesting highlights from his past, and focuses on the keys to his success at creating successful commercials for his clients. Be sure to check out this month’s RAP CD for an inspiring sample of Steve’s work.

JV: How did you get the bug for this business?

Steve: Well, my family was in radio back in the ‘50s. My mother sold for WWRL/WRFM in New York. My father sold for “Wins 1010 New York, ‘ding’”, as it was known back in the late ‘50s. So in about ’61, my father had an offer to go to Columbus, Georgia, to be a manager of a station – first sales manager, then general manager — and of course, we all moved there then. In high school I had no interest in radio. I was going to be a junior high school band leader; that was my big thing. But I’d go and play at those stations during my father’s sales meetings on Saturday mornings.

My family’s always been kind of artsy and so forth, so I kind of just fell into it. When I got older I needed a job. First I was in college, then in this JC Penney company management training program, and I was not happy. My father says, “Come on, try radio, come on!” At the time, he had bought his first station in Phenix City, Alabama, WPNX. This was in 1969. I said, “Okay,” and did my first shift, midnight to 6:00 a.m., in Phenix City, Alabama, right across the river from Columbus, Georgia.

I airchecked myself, and it is the most horrible aircheck you could ever imagine. I used to pull it out when I became a Program Director later on for people who felt like they were never going to get anywhere. I’d pull this out and say, “Listen to what I used to sound like,” just to give them a little bit of encouragement because it was so bad.

In 1970, my parents bought a station in Dothan, Alabama, WDIG, so I moved there. It was a family business. My brother was in sales; my brother-in-law was in sales; of course, my father was the manager/owner; and I was on the air. I became Program Director within a couple of years. This was a five-station market, 40,000 people, but we owned the market. We had over 50% of the audience doing basically what was tight, top-40 radio at the time, and of course, AM radio ruled the world in those days. FM was something people listened to for Montovani or long-hair, progressive rock music, but it wasn’t really commercially viable. AM ruled the world and we dominated.

I got to the point where I felt like people would think I’m Program Director because I’m the boss’s son, not because I had the talent to do so, so I left the family business to go to Florida because, when I was in college, I was in Miami, and I considered myself a Floridian from that point on.

I worked in Orlando, in Ft. Myers, in Cocoa Beach, in various Florida stations as Program Director, on air, morning drive, various things. I think I’ve done every job in radio with the exception of being an accountant.

JV: When did production creep into your list of talents?

Steve: Well it was around this time that I started to see that my strengths were really in production. I loved doing production; that was like my favorite thing to do when I got off the air, my production shift. Actually, I was into production back in the first couple of years at WDIG. Our Program Director then was Larry James, and he was a guy who was basically a big jock in Columbus, Georgia, before he went to Dothan. He was doing imaging and production in Dallas at KPLX, and I think he recently retired, but he influenced me in trying to push me into doing more than one style, and how to just look at a piece of copy and interpret it for style. And I loved writing; I’ve always been a writer. I’m desperately trying to find one of my earliest good commercials [for the RAP CD], a spot for a typical corner grocery store called Murphy’s Markets. It was a 60-second spot. What I ended up doing was getting the usual laundry list of food items and prices and made it into a takeoff of the movie Ben Hur. It was The Adventures of Ben Him, and it turned out to be very funny, and everybody wanted to hear it. People would call in and request it. So it was like, “Okay, this is good.” The client loved it, and that’s when I discovered that was really my forte, but never really became Production Director until much later when I was in Florida.

JV: So basically, you’ve been into the creative/production side of radio since the beginning, over 35 years.

JV: So basically, you’ve been into the creative/production side of radio since the beginning, over 35 years.

Steve: Yeah, and I went through two major revolutions in radio. The first one when AM got killed by FM, and then we went through two decades of tightly-formatted FM radio, eight minutes an hour of commercial breaks, and that kind of thing. Then, of course, the second revolution was deregulation 15 years ago, which changed everything again. Now we’re up to 18 minutes of spots an hour and everything clustered and grouped, and you’re not working for the guy in the corner office anymore. You’re working for the group.

But yes, the production thing has been with me for most of this time. I loved the writing, and I loved the idea of starting off with a blank piece of paper and then creating a spot that works for a client, and that was a long road to actually learn how to do that. When I finally was able to just be Production Director and not have to do an air shift anymore, that’s when it really fell into place.

JV: How did the full time Production Director thing come about?

Steve: In the early ‘90s in Florida, I was Production Director and afternoon drive at WINK FM in Ft. Myers. I had the best studio I ever had as Production Director. The air shift became sort of something I had to do, and I couldn’t wait to dive into production because I loved it. We had a recording studio set up as opposed to a production room, and we sold it as the Super Studio. It had a 32-track machine with the tape going by at 30 inches-per-second, and then 2-track reel-to-reels to mix down to. It had every toy available. It had mikes that could be isolated from each other in a huge cavernous recording studio room. That, to me, before digital came along, was the coolest thing in the world. It was from this studio that I started winning Addy Awards.

At the time, it was like 1992, I got tired of seeing what Florida was becoming, which was basically wall-to-wall condos. You couldn’t get to the beach anymore. There were the tourists, it was overcrowded, and I thought, “Okay, maybe it’s time to climb the major market ladder, see where I can really go.” I had just won the prestigious Charlie Award at the ’91 Addy’s in Miami for the Florida/Caribbean region, and so I thought, “Okay, maybe I do know what I’m doing, perhaps, maybe.” So I thought, “Okay, time to hit the road and see what’s going on up North and climb that major market ladder.”

I was targeting toward Denver because my brother lived out there. I started sending out tapes and resumes, blind boxes and so forth, and I got a response, a really good one, from Dayton, Ohio. I went, “Dayton, Ohio?” So they flew me up, and I took a look at it. It was market 54, and I went, “okay.” The facilities were top-notch, and I was just Production Director, not on the air, and I was able to focus on doing what I really love to do. I spent two years there, got a couple more Addy Awards, and then I got an offer from Cleveland.

This was in ’96, and I went to Light Rock 106.5. When Clear Channel bought us, it became Mix 106.5, and I loved it there. Cleveland was a cool town. But then the changes started to affect production because instead of just producing for Mix 106.5, my spots were airing on the group. It was a different time in radio, I noticed, because when the book would come in, instead of everybody crowding around in the PD’s office going, “Ooh, cool,” and everybody feeling like the family working for this particular radio station, it became like, “Well, okay, Mix is up, ‘TIM is down, and the other station is down….” You didn’t have the emotional involvement for your radio station any more. It was more of a group thing and, “Yeah, okay, this station’s up, this station’s down,” and it became more like working for a factory.

At that time, you started to see such things as copywriters disappear. Salespeople had to begin writing their own copy, and I really didn’t like that because salespeople are not equipped to write copy; that’s why they’re salespeople. Some may have some talent, but for the most – no. So at that point, in 1999 I had an offer to go to Pittsburgh for a union gig, which was Chancellor Media, which became AM/FM, which became Clear Channel. I went to Mix 96.1, which was down the hall from ‘DVE, a legendary station, and that’s when things were changing even further – equipment-wise especially. I started working with Pro Tools in ’96. That was a huge change in the way we do things. I had been reading about digital production, and I got to play with an Orban DSE 7000 in the earlier ‘90s, but this was like the coolest thing in the world. It suddenly made that huge studio in Florida that I loved so much obsolete because everything that was in that studio was in the computer. That made production so much different, easier in many ways, but it allowed you to be a lot more creative because you didn’t have to think linear. So I was using Pro Tools in Cleveland, as well as in Pittsburgh, and then it was one of those deals… they blew up the format that I was at, so, of course, all of us are out of a gig, and I ended up in Detroit at 97.1 FM Talk, which is a CBS facility.

At that place, the emphasis seemed to be more and more that they didn’t care what was on the air in the breaks. It was like a salesman can throw a scrawled piece of copy on a piece of legal paper in a production basket at 5:30 in the afternoon and expect it to be on the next day. I got there, and there were two assistants. Then I had one assistant. Then it was just me, and so, of course, my voice is on everything. Being a talk station, it’s not like you have jocks that do a production shift, and it was like they didn’t seem to care. I was seriously thinking about getting out of radio at that point. I thought, “If this is what radio has become, it’s not fun anymore. I’ll go back to Florida and open up a landscaping business.”

That’s when NextMedia made me the offer to go to Dreammakers Productions in Chicago, and I loved that. That was almost like being in an ad agency, because at that point, we got to work with the client — actually work with the client... what a concept! You find out what it is that makes that particular client unique. You talk to them, get in their head and get their story, and then write spots around that story. What is unique about them? How to position them versus their competition, and then have the luxury of a stable of voices all across the country to draw upon to voice the spot, and then produce it and send it off to the client.

That was wonderful because you can go in there and look at a script you wrote yesterday and make changes because you’re seeing it with fresh eyes. You have time to work and to finesse it until it’s finally at a point where you think it’s fine. And then in the production process, it’s the same way. You can produce it one day, go home, come in the next day, listen to it and say, “You know, if I put a little plate clunk in this particular bit at a particular point, it’ll make it so much better.” A little ear candy, because radio is theater of the mind. So you’re able to finesse it, and you’re able to have the time, which, of course, in normal commercial radio, you don’t have because you’re always working against deadlines.

I loved that job until they pulled the plug on Dreammakers about 2½ years ago, and that’s how I ended up here in St. Louis. A new Program Director here at KTRS said, “Hey, Steve, come on down, let’s talk.” They flew me down and I liked what they were doing. In many ways, KTRS is a throwback to the way radio used to be before deregulation because we’re not part of some giant group across the country. We are basically a stand-alone, owned partly by the St. Louis Cardinals and a group of investors. The guy in the corner office is the guy you talk to.

JV: This is a good example of one of those rare stand-alone stations in large markets that’s doing very well against the big corporate competition. It sounds like you went from Dreammakers to one of the few dream jobs left in radio.

Steve: To make a long story short, I’ve been there two years, and I have yet to have one bad day. You have some days where things are a little out of control because of the volume of stuff you have to do, but I’ve never had a bad day. When I came I told them what I needed, and they set me up with Pro Tools and that kind of thing in the studio. They are very responsive to the needs. They understand that the client is the most important person that we’re all working for, and the quality of the product is important on the air. It’s nice to have that kind of support, because I’ve been in other instances where they didn’t care.

Of course, when you’re the new guy, you have some hurdles to overcome. You have salespeople who send a production order with copy they wrote and want read word-for-word. Well, the copy sucks. There are no verbs. It’s just a laundry list with a cliché. It sounds like every other spot that has ever aired on radio since Marconi. So I would get around that. Instead of arguing with them, I would explain to them that this is not really a good idea. “Why don’t I come up with an idea, and that way you’ll have two spots to play for the client?” — my version and of course his version. That was the best way to get around that kind of hurdle because once the client started to say, “I like that other version better,” I won.

I wasn’t hired to write — which nowadays it seems like most stations seem to emphasize that the salespeople should write spots — and as I mentioned earlier, salespeople are not the best in coming up with a creative concept. They tend to be order takers. The client wants all this in the spot; they somehow write all of this in the spot as opposed to trying to figure out what’s important to the listener, the customer of the client. What’s important to them, and what is the one thing about this client that’s unique that we could talk about in the spot that would make the listener pay attention?

Since deregulation, it has become so much harder for a client to get noticed on the air. Back when I was on the air before deregulation, when it was eight minutes of commercials an hour, if you were the third spot in the break, I used to worry that they’re not going to be heard. Then, of course, we go into a jingle and we’re back into music. Nowadays, when you have an 8 to 10 minute break of spots, one after another, it’s so much harder to be heard. You have to have much better production today for the spots to actually work for the client than in those days.

JV: You came on board as the Creative Services Director. Have your responsibilities changed since then outside of writing more?

Steve: The only way it’s changed is the writing... more and more writing. The salespeople now come to me and depend on me to write more of their work. They might come with an idea. There’s a couple of salespeople there who are talented with ideas, and they’ll write a script, and then they’ll come to me with the script and ask my opinion, and we’ll kind of flesh it out and make changes and so forth. Most of them, though, aren’t very good at writing, and so I’ve picked up the slack. But I don’t mind it because I love the idea of a spot actually working for the client, and if I’m gonna spend time doing that, it may as well be the best we can do for the client.

JV: Do you have to deal with any of the imaging for the station?

Steve: No. I do promos for station events, but we farm out the imaging.

JV: Have you created a similar setup there at KTRS like the Dreammakers setup in Chicago, kind of a for-profit agency within the station?

Steve: No. The difference with this, of course, is the fact that, number one, this is a volume business, and you never know what’s going to be coming onto your plate for the next day. I wish I could. There are some clients who have liked my work and have paid for my work — for my Captain Voiceover stuff, my little side business — but for the most part, no. Everything that I do there is strictly in the job description.

Now, I would like to do something where I could spend more time with clients, but the difference between Dreammakers and normal radio is you have the buffer of the salesperson, and some salespeople get a little nervous when somebody else is talking to their client, whereas at Dreammakers, Walt Koshnitzke [Dec. ’04 RAP Interview] was on the road and had the first contact with the client. Then after that, I had the full contact on the phone with the client — or if they happened to be in the market, face to face — to try and get their story. So we didn’t have the buffer of a salesperson.

JV: Why do you think copywriters are disappearing from radio?

Steve: I don’t know, and that’s been one of my laments because we’re asking a client to spend a ton of money, “Advertising pays, you need to get your message out.” And in most cases, salespeople tend to be order takers; they don’t want to rock the boat because they have this list of stuff the client thinks is important, which in reality, really doesn’t matter to the listener.

Who cares if you’ve been in business for 30 years? — “Been in St. Louis since 1932.” Who cares? “What can you do for me now,” is what the listener is asking. Why should I go to your store rather than the guy down the street who does, basically, the same thing? You’ve got to find the one thing the client does well that people would be interested in hearing the story about. Sometimes it could be the client has a particular passion for what they do, and you can develop a story around that.

It’s tough. Sometimes you get little time. For example, I think it was on Wednesday, a salesperson comes in with a last minute order for Ozzie’s Sports Bar. Ozzie Smith is an exCardinal star who has a sports bar in the same complex we’re in. So he came in, and he didn’t have much in copy facts. It’s a 30 second spot, needs to be on the air tomorrow. What am I going to do? Well, he says they’re basically promoting they have football on the screens. Well, every sports bar has football on the screens. What’s the hook here? Well, I thought, “Okay, football. It’s an f-word. Ozzie’s Sports Bar is about to say some fwords, and here they are – food, fun, and football…,” and I built the spot around that.

It’s just looking for that little hook, which salespeople for the most part can’t see. They’re too busy moving on to the next sale. And if a client’s not happy, you lose the client, which means the salespeople have to spend more time out there trying to get new clients to replace the old clients. So I really do not understand why copywriters have disappeared.

A radio station could have a copywriter on staff to free the salespeople to actually go out and sell, as opposed to sitting in front of a computer all day trying to figure out what to write. So, in my way, I’ve taken over that aspect. Some of them still write the basic idea, and I’ll flesh it out and revise it and then get it on the air for them. But I don’t see the trend going in the other direction.

JV: You’ve been there handling the clients now for a couple of years. How’s it working for KTRS and the clients? Give us some success stories.

Steve: Well, where I’ve been involved, there are numerous cases where clients were so happy with the spots and the responses that they renewed their schedule. They are extremely satisfied, and with the guy I replaced, they didn’t have that kind of story.

Also, for two years we’ve never missed a spot because of a problem in production, and that’s always been a case in a lot of radio stations where for some reason or another, the schedule starts and the spot’s not ready, or somebody forgot to cart it up, or whatever, blah, blah, blah. It’s organization, pure organization, to be totally organized in the department, to ensure that things get done in a timely manner because you never know when traffic’s going to walk in at 3:00 in the afternoon with stuff that needs to be on the next day. There’s no way to know the volume that’s coming in, so you’ve got to do the best you can in the limited time you have to ensure a good product.

Sometimes I’ll revisit a spot a couple of days after it has been on the air. I’ll hear it on the air and I’ll think, “You know, if I did this and changed it a little bit, it’ll be even better.” It’s just a regard for the final product that makes everybody happy.

JV: What are your thoughts on having the client voice the spots?

Steve: I usually don’t like having clients on the air because they tend to sound like they’re reading, but, in some cases, you end up having to deal with that anyway. You have to pick your battles and try not to make waves and explain the reasoning why you think it’s not going to work. But if you lose your battle, you continue on with a smile. Never be negative.

So you get the client in, and one thing I have a tendency to do is entertain them while they’re in the production room because they’re nervous -- they’re sitting in a room with microphones and so forth. So I try to entertain them just to loosen them up. This could even apply with sports stars. Being the Cardinal station, we sometimes get sports figures in. We had Albert Pujols, the star baseball player, in the other day to do some spots for Pujols 5, his restaurant, and he’s from the Dominican Republic. He doesn’t speak English very well, and out of 18 minutes of audio, I had enough to put together the two 10-second spots and a phone message. It’s a case of making them comfortable and making them feel secure. When they leave the room, they’re happy, and then, of course they’re happy with the final product.

I may be paid by programming, but in a way, I’m part of the sales department. You have to think that way in order to be successful in what you do, if you’re in a position like mine. Any time somebody brings in a production order, it’s not, “Oh, great… another production order.” It’s like, “Okay, how can I make this work?” It’s a challenge.

JV: You mentioned spots coming in late in the day that start the next day. Do you not have deadlines in place for sales?

Steve: We have firm and hard deadlines. In fact, it’s a pleasure because I’ve worked in too many radio stations where there are no deadlines whatsoever, and they didn’t care. We have firm and hard deadlines about when a traffic order has to be in and when production has to be in, which is what makes a very happy atmosphere, because people know the deadlines are ironclad. But also in radio, we know circumstances happen which create a situation where something has to come in past deadline. That does happen, and we can’t say, “I’m sorry, I’m not going to do that. It’s past deadline.” You have to basically understand that this happened, it has to be on, and okay, this is what we’re going to have to do to get it on and get a good product on the air. You can’t be sitting there staring at the clock thinking, “Okay, it’s 5:00 p.m., I have to leave now.”

JV: How much turnaround time do you ask for on a spot that has to be written and produced?

Steve: I like to have at least three days. It doesn’t always happen, but I like to have at least three days, because I do like to be able to do a little research. Sometimes you need an idea. Occasionally you can use the tools at your disposal. The Internet’s a wonderful thing. You Google in a word that has to do with the spot and boom! You get all kinds of information you might be able to draw upon. Then you have the germ of the idea, and I tend to hear the spot when I’m writing it. I’m hearing it in my head, and I tend to write broad. So if it’s a 60-second spot, then you’ve got to pair it down to 180 words to make it a 60. But, yeah, I like to have the time so I can revisit it. And sometimes you can, sometimes you can’t; you just have to write and get it produced.

The other aspect of this is the voices I can draw upon. Generally, they are in the building in the morning only. Being a news/talk station, it’s not like I can have jocks come in to do production shifts. It’s a case of what voices are available, and unfortunately, since there are not that many voices available, I have to write knowing the limitations of what is available. There are some people who can play roles, but I can’t give them that much to say, and when I get them into production, I might tend to coach them through the part rather than having them read it. I’ll tell them the line, they’ll tell it to me back until I’m happy with it.

JV: You mentioned Google. Where else do you go for creative ideas when you’re trying to put something together fast?

Steve: When you’ve been doing radio since ’69, and an avid listener since the late ‘50s, you’ve heard a lot of commercials, and sometimes some ideas stick in your head. In advertising, I don’t think anything’s totally new, so it might be just an approach that you could use. There are certain things I detest – contrived conversations, for one. We had a jewelry store a week ago… their idea was to have the husband and the wife talk about the jewelry that he should get for her for Christmas, and why he should go to this particular jewelry shop. Well, it was the typical, client-written, contrived situation, written in paragraphs the way people do not talk, and it’s the best way to make people tune out. It becomes what I call audio wallpaper. So I ended up having to take that and rewrite it because the client was insistent upon the husband/wife conversation. So you end up writing in short, choppy sentences with plenty of interruptions by the other person as they’re reacting to what’s being said, to try and put it into words real people would use to talk about it.

The trick is to try and figure out how to get this required client information in there without it sounding like the required client information, and so I ended up getting a spot that was a compromise. It’s not the best in the world, but the people doing the male/female part sound natural talking about it, and I used the announcer tag at the end to put in the rest of the required information so the characters in the spot wouldn’t talk like that.

As far as getting ideas, in a way it’s just observing life. I observe people and see what they do, how they talk, and hear what they say. Sometimes that’s a germ of an idea which I may put away to use in the future. I do have the recycled old ideas. I save everything. I have copy from back before there were computers. I printed out everything that I ever thought was good, and I have a file on that stuff. So sometimes I might dig out something I used 20 years ago as an idea starter and go from there.

JV: What tips would you offer our readers that they could use immediately to start improving the product coming out of their studios?

Steve: Number one, don’t be afraid of criticism. You should not get your feelings hurt. You cannot have a thin skin in this business because you may have a spot that you think is the greatest thing in the world, but in reality, it may not get the actual message across for the client. It may be the most entertaining thing in the world, but it’s not really getting the message out, and if it’s not working, don’t be afraid to move on to something else.

I did one for an investment firm that I thought was really good, but his phone wasn’t ringing. So we met the other day, the client and I, and decided to use a whole different angle, because, at the time we were talking, he was becoming passionate about what he was doing. I said, “That’s the secret. I want you to put down some bullet points, come into the studio with me next week, and I’ll just record you being passionate about your topics. Then I’ll cut it down and we’ll build spots out of that,” because I thought, that is what’s going to connect with the listener. Here’s a normal sounding human being, being passionate about what he does and what’s good about it, as opposed to another typical voiceover announcer doing a commercial for this particular investment firm.

Don’t get your feelings hurt if it’s not working, or if somebody has any criticism about it. An awful lot of times you run into approval by committee, which you know is going to be a disaster because they’re going to take the spec spot out there, and the client’s going to listen to it, and his brother-in-law’s going to listen to it, his wife and the kids and everybody, and somebody’s going to find something wrong with it. It’s a case of, “Well, okay….” Then we’ll come back with version two.

Another thing, don’t burn any bridges. You never know… you may link up again with people that you used to work with years ago, or they may recommend you for a gig. You should never burn any bridges, and you should always be learning. You never know everything. All the seminars that you can go to? Go. Creative copywriting? Go.

Practice – when I first started, I would be sitting in the car driving along, and I’d hear a commercial on the radio, and I’d mimic the voices and try to figure out – how do you do an old-man voice? I’d hear an old-man voice on the radio, and I’d be trying to mimic it. You pick up the style.

If you’re trying to be successful in this business, you’ve got to find out what is really important to the client and what will make it work. What is unique about this guy? What is his story? What can we use in this spot? Keep it one thought per commercial. If there’s two or three different items or services they’re promoting, that should be two or three different commercials. No laundry lists, no contrived conversations.

Always be entertaining, be up, be happy, and don’t be negative. Don’t get your feelings hurt, because they can always look upon that and say, “This guy’s a pain in the butt. We need to make a change here.” You’ve got to do everything with a smile.

JV: Who were some of the people that made an impression upon you with their creative works, some of your mentors?

Steve: Well, back when I first started, Larry James was the first person who kind of set me into trying to be not just a guy reading copy, to try to interpret it, try the soft approach, the hard sell approach, the very basic approaches, because I was just starting in radio then.

I worked with a guy who people may have heard of, Dan O’Day, back when nobody ever heard of Dan O’Day. He was at WIPC Lake Wales, Florida in the early ‘70s. He was doing mid-days, and I was doing afternoon drive. I even have an air check that has some of his early commercials on it. He’s, of course, gone on to be very strong in the creative end of commercials. I’ve learned a lot from him.

Dick Orkin was a huge influence. I loved Dick Orkin’s style, and that’s one of the things that got me into creative commercial writing. I would listen to anything Dick Orkin produced and go, “Wow!” It would just blow me away because he always approached everything with humor, and somehow kept you listening. That’s the hardest thing in the world, to try and get this message across in 60 seconds, or 30 seconds, and keep the audience – the target for that particular client – interested in the spot, to make an impression. Take a spot for a carpet dealership — “You know, I think we really do need to change the carpeting in the living room, it’s getting a little worn out. Why don’t we start shopping around and go to this place we just heard about?” That’s when you’ve actually connected with the listener.

But Dick Orkin, with his style and his humor — even though I’ve never met the man — has guided me onto a path, because I do love humor. I think that humor done right, not just to make a funny, but just in making the point, works for the client and keeps the people listening. It is harder to keep the audience through the much longer breaks today than it was back before deregulation, and so it works both for the radio station as well as for the client because it keeps people there.

JV: What’s down the road for you? Are you going to work your freelance business into an advertising agency?

Steve: I’ve done freelance stuff on the side for like a couple of decades. One of the nice things of being in the Chicago-land area was that I got a lot of outside work there. But since I’ve moved to St. Louis, that’s kind of slowed down, except for a couple of ISDN sessions where they wanted me to voice something, but for them it’s more expensive than me actually being available to be in a studio in Chicago. So I’m building my Captain Voiceover business on the side.

One of the things that I see so much is that the emphasis in all the trade magazines seems to be on imaging. Imaging, imaging, imaging. I’ve done imaging too, but I don’t see the emphasis on the commercial production aspect. I rarely see any articles in any trade magazines, with the exception of yours, on commercial production. It’s like it doesn’t exist, but yet, if you’re in commercials for a fifth of each hour, I would think that that would be one of the most important things you could talk about in any radio trade magazine.

I really feel that for some reason radio has forgotten what happens when you’re out of normal programming. In the old days when we had a commercial break, we would stack our carts up an hour ahead of time, and we’d do voice separation. We had a system to separate the good spots from the bad, and we would program each particular break to have the hot, full-sing jingle spot first, the Budweiser beer spot, and then bury the crap in the middle.

We also used to have intro times on spots with the jingle so we could talk up the jingle. And we played our breaks manually, and they were programmed like the rest of the radio station. Since computers came in, it seems like breaks are used for a bathroom break. So whatever order the computer plays the spots in — and we’re talking about maybe eight spots in a row — is the way they come across on the air. That also is a giant step backwards. I think it’s a mistake. Commercial production seems to be the poor stepchild in a lot of radio stations. They’ll get somebody just out of college who can crank out crap.

♦