by Steve Cunningham

Podcasting. Everybody and his uncle Bob is podcasting. Often podcasting is little more than remote recording, which we all do now and again. But beyond the actual activity of creating, editing, and uploading, podcasting is important to me because it represents an opportunity to engage in one of my favorite activities — checking out new gear! Woo-hoo!

This month we’ll look at a couple of affordable USB microphones that plug directly into your laptop. While they both were clearly designed with podcasting in mind, they’re also appropriate for remote recording in general. Let’s see how they fare when used to interview the owner of Honest John’s Used Car Emporium for a commercial campaign. Do they capture his sincerity well enough to air?

BLUE MICROPHONE’S SNOWBALL

The Snowball is the latest in Blue’s series of microphones with a “- ball” suffix in its name (what’s next, the Eyeball?). Clever name aside, the white resin casing with wire-mesh grilles at front and rear contains two condenser capsules, one with a cardioid pattern and one that is allegedly omnidirectional (more about that later). No phantom power is required, as the Snowball gets its power from the USB bus. A threaded stand-adapter is set into the base, and the mic comes with a slick little table-top tripod stand, plus a USB cable for connection to a computer. A shock mount called the Ringer is available as an accessory, although its price is two-thirds of the mic itself. For desktop use it is not necessary.

Besides the USB port that is the microphone’s only connector, there is also a three-position switch at the rear. Position one activates the cardioid capsule, position 2 inserts a -10dB pad into the cardioid capsule’s signal path, and position 3 activates the omni capsule. No phantom power is necessary, as the mic gets its power directly from the USB bus; a red LED indicates that power is active.

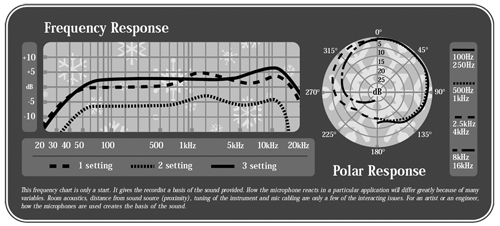

Blue lists the Snowball’s overall frequency response as going from 40Hz to 18kHz, although by looking at the response curve it would seem this is plus or minus 6dB, with a presence peak at 3kHz in cardioid mode and at around 10kHz in omni mode.

The Snowball works with computers running Windows XP or Mac OS X without the need to install additional drivers — all you need is a free USB port. From inside your digital editing software the mic shows up as two identical input sources rather than as a single mono source (one source for each capsule). The analog-to-digital converters built into the microphone are fixed at 16-bit and 44.1kHz.

SNOWBALL IN USE

SNOWBALL IN USE

Blue says the Snowball is a good general-purpose vocal or instrument mic; their examples in the manual show you how to mike up various instruments. But it’s also clear that they intend this mic for podcasting, and I’d like to use it for remote recording in general.

The Snowball’s fixed 16-bit resolution is plenty for podcasting (and for most speech, really). You’ll get good quality sound from the Snowball, provided you can run it at or near maximum level to make use of all the available dynamic range. But if you run the Snowball at low volume into your editor and use only a small part of the dynamic range, you won’t be getting the best resolution possible and will end up with audible background hiss to boot. For example, if you record in 16-bits at an average level of -24dBFS (that’s decibels below full scale), then you are only exercising the bottom 12 bits of each audio word, and you’re essentially recording at 12-bit resolution rather than 16.

With a conventional remote recording setup, you’d have a mic preamp between the microphone and your computer’s audio input, perhaps built in to the audio interface, to help boost the average level of the mic signal before it hits the analog-to-digital converters, which would help get your resolution up. But with the Snowball, the preamp is in the mic itself, and you can only switch a pad in or out of the signal path.

With a conventional remote recording setup, you’d have a mic preamp between the microphone and your computer’s audio input, perhaps built in to the audio interface, to help boost the average level of the mic signal before it hits the analog-to-digital converters, which would help get your resolution up. But with the Snowball, the preamp is in the mic itself, and you can only switch a pad in or out of the signal path.

I set the switch to position one (cardioid, no pad) to begin the evaluation. When I used the Snowball to record voiceovers in the studio, with the talent relatively close to the microphone, the average signal level produced was fine. But when I put it about a foot away from the talent (as it might be in a client interview situation), the recorded level of speech averaged out at less than -20dB. As noted above, this gives a resolution of just over 12 bits — not good. I much prefer an average level of -12dB or more, so I’m getting at least 14 solid bits of audio data.

MICROPHONE SOFTWARE?

Evidently I am not the only one who was concerned with the default low level of the Snowball, because Blue recently posted a pair of software “applets” (little applications), for both Mac and PC that modify the microphone’s firmware to change the output level. Running the “UpdateSnowball high gain version” applet raises the output level quite a bit, according to Blue between 12 and 18dB. Running the “UpdateSnowball low gain version” sets the output level back to its default setting. After running the high gain applet, the mic had plenty of level at up to 18 inches away from the talent, and background hiss was low and acceptable, especially given the price point. When working close to the talent after running the high gain applet, I actually had to engage the pad by setting the switch to position two to keep from overloading the mic.

I then switched the Snowball’s switch to position 3 to check out the omnidirectional capsule, which I figured would be useful for the client conversation scenario. Note that the grille is open only on the front and back, but not on the sides, and I wondered how this would affect its sound in omni mode. It does indeed, as is shown by the polar pattern diagram. As it turns out the Snowball listens primarily from the front in both cardioid and omni modes, and the sound from the rear in omni mode is muffled when compared to the sound from the front. The tone character changed as well in omni, since as you can see in the response graph, the midrange bump in omni mode is much higher up than in cardioid mode. I like the sound of the omni mode when using the mic straight-on, which has an airy quality to it that is surprising for an inexpensive mic. I was not impressed by the Snowball’s sound directly from the back, so I tried it in omni with two VOs sitting near each other rather than across. The microphone acted as a very wide cardioid, and picked up both voices equally well. It’s not a true omni, but it worked in that scenario.

The Blue Snowball produces very good-quality results, providing you set things up to get a healthy recording level. Like many multi-pattern microphones, the Snowball’s omni mode is best considered as a different tone color compared to the cardioid modes. The mic’s pickup pattern is not truly omnidirectional, and I wouldn’t consider the mic to be well suited to recording round-table discussions in this mode, but used appropriately, its sound quality is fine and the background noise acceptably low. If you are going to use this mic for podcasting, it will produce the best results if you speak into it from around six inches away, and you can choose omni or cardioid mode depending on which tone suits your voice best.

With an accessory pack that includes a USB cable and mic stand, the Snowball carries a list price of $189 MSRP, and a street price well under $150. Visit www.bluemic.com for more information.

THE SAMSON C01U

THE SAMSON C01U

Samson’s C01U microphone is a USB version of their entry-level C01 medium-diaphragm condenser microphone. Like the Snowball, it outputs a 16-bit resolution signal, but unlike the Snowball it supports sample rates of 8, 11.025, 22.05, 44.1 and 48kHz. Samson is known for developing low-cost audio products, and the C01U is no exception with a suggested retail of $235 but a street price of under $80 (that’s some discount! Someone ought to talk to Samson’s marketing department about inflated list pricing).

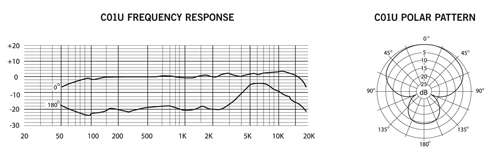

The die-cast metal C01U microphone resembles a traditional side-address studio condenser mic, feels reasonably solid, and is nicely finished. It uses a 19mm cardioid back-electret capsule with a three-micron diaphragm, suspended on an internal shock mount. Its frequency response claims to be flat within 1dB over the audio range. Its maximum SPL specs out at an adequate 136dB, but there are no noise specs, a possible cause for concern. There are no pad or low-cut switches on the mic itself, although a software applet does provide a very effective low-cut filter with variable cutoff frequency. A green LED on the mic confirms that USB power is active.

It would seem that USB microphones have a genetic disposition towards low output levels. The C01U addressed the “low volume” issue right from the gate, by adding a two-stage variable gain cell inside the microphone before to the converter. If you just use the mic as it comes, your computer’s own system gain control actually controls the mic’s internal gain cell. However, as documented in the manual, you can also download Samson’s control panel applet, called Soft Pre, and this can be used to control the internal gain of the mic. Up to +48dB of additional gain is available, and the applet also provides metering, variable-frequency low-cut filtering and a phase invert switch.

IN USE

Once I’d connected the mic, it seemed that there was a bit more latency than I expected for the buffer size I normally use in Adobe Audition (and more than the Snowball). The talent that helped me did not find this to be a distraction, although some might. In any event, so long as you can work with buffer sizes of 128 samples or less the latency is fine.

The C01U’s pattern seems really to be hyper-cardioid, and it does a good job of rejecting side and rear sound. It does generate some self-noise however, which appears as low background hiss that I assume comes from its internal circuitry. The noise was particularly evident on softer voiceovers, but by keeping the mic closer to the talent and the level up via the control applet, the self-noise was manageable and acceptable for a microphone at this price point.

Sound-wise the mic is neutral, with a very slight presence bump up at the high end of the frequency spectrum. As it is a condenser, it does better with transient details than a similarly-priced dynamic mic would. It can certainly be used to record respectable voiceovers, but I wouldn’t choose it for critical voice imaging work.

The Samson C01U comes with a 10-foot USB cable, a fabric carrying pouch, and a plastic stand mount (but not a stand). As mentioned, it carries a suggested list price of $235, but is commonly available online for less than $80. Visit www.samsontech.com for more information.

WHICH ONE?

Either of these USB microphones would be fine for podcasting, which is where we began this review. Past that however, there are some differences between them other than pricing. The C01U is not quite as present as is the Snowball in omni mode, but it does pick up low frequencies better. Unfortunately it also generates more self-noise than the Snowball.

The Snowball definitely has the edge in terms of its coolness factor, and the dual-capsule design makes it more versatile. Unfortunately, neither microphone will pack well into a small remote kit — they’re both bulky to carry. Moreover, I’m sure that we’ll see 24-bit USB mics in the future, and hopefully ones with better methods for controlling gain prior to the converters. But right now the amount of current that can be drawn from the USB buss is the limiting factor for both of these microphones.

I think that for now, I’ll delay any decision-making... there are a couple more small mics I want to look at yet.