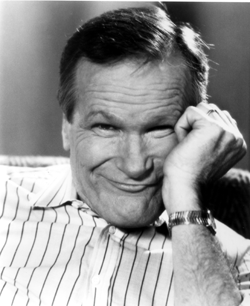

Chuck Blore, The Chuck Blore Company, Los Angeles, California

Broadcasting Magazine calls Chuck Blore “...a legend in the radio and TV industry.” Regarded as one of the originators of “Top Forty” broadcasting, Chuck was named Broadcastings Man-Of-The-Year three successive years for “Original concepts elevating both the entertainment and the communication levels of broadcasting.” His “Color Radio” concepts for KFWB in Los Angeles transformed the face of modem broadcasting and made KFWB the most listened to station... ever. Before or since. The station averaged over a 30-share of the Southern California audience for over six years until Chuck left to form his own creative services company.

Broadcasting Magazine calls Chuck Blore “...a legend in the radio and TV industry.” Regarded as one of the originators of “Top Forty” broadcasting, Chuck was named Broadcastings Man-Of-The-Year three successive years for “Original concepts elevating both the entertainment and the communication levels of broadcasting.” His “Color Radio” concepts for KFWB in Los Angeles transformed the face of modem broadcasting and made KFWB the most listened to station... ever. Before or since. The station averaged over a 30-share of the Southern California audience for over six years until Chuck left to form his own creative services company.

The Chuck Blore Company has won over 400 major radio and television awards making it, what Adweek Magazine called, “Probably the most honored company in the history of broadcast advertising.” In 1976 he created “The Remarkable Mouth” TV commercials for radio stations which have been on the air, somewhere in the world ever since. 2001 marked the 25th year of continuous exposure for “The Mouth.” That’s gotta be a record.

Chuck is the only person ever to have won both of the most coveted awards the Television Promotion Industry can bestow: The Professional Achievement Award and induction into the Hall of Fame. The radio industry also honored him with the Lifetime Achievement Award and induction into The Hall of Fame.

Imaging, branding, and corporate positioning are other arenas in which the work of CBC has been honored. The launch campaign for The Learning Channel swept the International Film Festival Awards in Houston winning the Gold, Silver and Bronze awards. Corporate Films for Tri-Star, Columbia and ABC TV have been recognized for the “Level of significant achievement.” NBC, CBS, ABC, FOX, DISCOVERY, TLC, CNBC, TLN, and many others have used the creative services of CBC.

The Chuck Blore Company expanded into program production in 1995, when Chuck wrote, produced and directed (with a little help form some friends) a 60-minute TV special, “The New Adventures of Mother Goose” featuring Sally Struthers and Emmanuel Lewis. Chuck received an Emmy nomination for “Best Directorial Achievement.”

Chuck has taught at UCLA, USC, and CSUN. He has spoken to advertising, broadcast and cable groups in every major city in America and in almost every English speaking country in the world where there is commercial broadcasting.

There’s a lot more stuff but that’s probably enough for now. This month’s RAP Interview gets some insight into both the programming and production side of Chuck’s legendary career. And we get a sneak peek at Chuck’s latest offering, Chuck’s Kids, a library of voice tracks and more from Chuck’s amazing archive of commercials involving child voice talents, a library that puts the core elements of some of Chuck’s most successful radio commercials into the hands of producers everywhere.

Read, assimilate, create.

JV: How important was production at the stations you programmed?

Chuck: One of the things I demanded of myself or whomever I was working with was that there be no flagging of attention or quality between the records. I wanted our production to stand up to the great music being turned out at that time, which was over 30 years ago. It was produced beautifully—the lyrics and the songs were, I thought, just incredible. The production of them was marvelous. We at the radio station had one choice: do superior stuff or have the radio station be the weak spot on our own radio station. And that we couldn’t afford to do. So, we were always highly produced between the records.

The commercials at that time were rarely done by the station. I’m talking about in Los Angeles in particular. Most of the commercials were produced by agencies and handed to us. And some of those were wonderful; some of them you hated. As a matter of fact, one of my rules at the radio station—and believe it or not I had this kind of power when I was doing it—is that I would not accept on our air any commercial that yelled at people. In those days, there was a lot of shouting going on. So if you were yelling at the audience, the commercials were not welcomed. Also if you were treating the audience like idiots, the commercials were not welcomed. The second one I had a little trouble enforcing because that was pretty much a matter of opinion. But I have always thought that I should have great, great respect for that audience. The audience who, merely by tuning in, has given me every possible thing I could want from them. And it seems to me that anyone who gives you every possible thing you could want from them, well you owe them something in return. So I was trying to give them every possible thing they could imagine plus. Obviously, they tuned in for the music, but in LA, when I was programming KFWB, there were sixty radio stations in the market, and two-thirds of those were playing popular music. So, you had to standout. You couldn’t just play the music. Again, it’s about what happened between the records.

JV: Do you think this policy of attention to what’s in between the records has stayed alive at well-programmed radio stations today?

Chuck: I think at the present time it doesn’t exist at all. And again, I’m talking about Los Angeles radio. The promotional material that I hear for the radio station are either little clips from the morning show to get people to listen to the morning show, little one line jingles or some staff announcer talking, and very little production going on. Now, there are some that are being produced, but it sounds like they’re being produced to pat the station on the back rather than with any particular deference to the audience and the intelligence of the audience.

JV: Why do you think that it has deteriorated?

Chuck: I really wish I knew that. The difference between when I was programming stations and now is that today, what every radio station points to with their promotional material, for the most part, is their morning program. The highest paid talent is on their morning program. The highest revenue is on their morning program. Then, at nine or ten o’clock in the morning, they turn to something else. Either a weak imitation of that morning program or, the heck with it, let’s play four or five records in a row and get as much music on as we can. And the difference between now and when I was programming KFWB and whatever other stations I programmed, we didn’t have that morning show and then stop things at 9 or 10. We had that high-priced talent and that high-priced promotion going on 24 hours a day. Now midnight to six we may have eased off a little bit, but other than that, every guy was an entertainer. Everything we did between the records was produced for the entertainment of the audience – everything. There was nothing too small to deserve attention.

JV: When did production become a major part of your arsenal? Was this something you got into right off the bat in your first radio job?

Chuck: A man by the name of Tom Wallace had a station in Tucson, which is the station where I began. He had been an NBC announcer in Chicago, and so he had this big beautiful voice. When I called him to apply for the job—my audition was a telephone call—he kept saying, “Well, you certainly don’t have much of a voice.” And I said, “Well, I like to consider myself an entertainer.” He said, “What are you going to do, tell jokes?” “Well, if that’s what you want.” He says, “I want good radio,” or something like that. So, anyway, I ended up working for Tom Wallace, and while he was a wonderful man and I loved him with all my heart, he constantly was saying, “Well, you certainly don’t have much of a voice.” And I think because of that, and because everyone around me in those days all had those big pear shaped tones and lived off them, I decided I needed something to make people listen to my programming in spite of the fact that I didn’t have much of a voice. So I began creating little comic characters. I started doing voices and writing little, hopefully, entertaining things to introduce my show. Three or four times in the hour, I would come across a pretty dull commercial and I would do voices and add comedy to it and that sort of thing. And that’s kind of the way it started. It was a matter of self-defense.

JV: Did you continue to produce these little entertainment bits as you progressed in the business?

Chuck: Yes. I soon was producing them at one of Gordon McClendon’s stations. Gordon, of course, in those days was tearing up Middle America with his radio stations. You look in any book and you see Gordon’s stations at a fifty share and the second station had a six. Gordon came driving through Tucson on his way from LA to Dallas. He heard my program and said, “Hey, I want you.” Back in those days, believe it or not, I was making $250 a month. Now understand this is fifty years ago! Anyway, I said, “You know, I’m doing okay here, Gordon. I don’t want to move.” And he said, “Well, you’ve got to come to Texas. I tell you what, I’ll make it $300 a month.” Well no one in his right mind could say no to that, so off I went to Texas and I worked for Gordon in San Antonio at KTSA for a year. And Gordon was always taking the things that I was producing to hide behind on my radio program, reproducing them in many cases, and using them for the other stations in his chain, just as general entertaining radio. I confronted him on this one day, and he said, “Yes, I’m doing that, and I think as a matter of fact that they have been very good for all our stations, and I would like to make you Program Director of our El Paso station.” And I said, “I don’t want to be a Program Director.” And he said, “You’re going to El Paso, and I think you’ve made a wise decision.” And that’s how I became a Program Director. So, of course, when I went there, now I had a whole radio station on which to put these things that by now I had fallen in love with thinking that this was what radio could be, because even then, I knew any station could play the music.

JV: So you continued to produce these bits in El Paso for all the other stations while you were programming the station?

Chuck: Oh, yeah. And I ran into a fellow there who was also in love with production, and he and I began to cook these things up mostly because they were so much damn fun, and that station was loaded with entertaining stuff. It was so loaded with entertaining stuff that our station in El Paso—and it was an eight-station market—had a seventy-four share of audience. [That’s not a typo folks…74, not 7.4] I think that’s unbelievable, and I don’t know that it could ever be duplicated merely because there are more stations today.

JV: How did you end up in LA?

Chuck: Well, it was that particular rating in El Paso that got me called to LA, which in spite of the fact it was my home, I could never get a job in radio in LA. The Crowell-Collier Publishing Company bought a station in LA, which was KFWB, for $650,000. They sold it five years later for $19,000,000. Of course, today, it would be up in the $100,000,000 area or more. Basically, they published encyclopedias and were quite famous for that. But their broadcast experience was nil. So they hired a man by the name of Robert Purcell who had been a damn good broadcaster and had a lot of experience. He had heard about what was happening with these Gordon McClendon stations. So Bob Purcell began looking through all the rating books, and he kept running across this little station in El Paso that had this seventy-four share. So he called me and asked me if I’d like to come to LA. I said, “Good God, man, I was born there!” Anyway, I came to LA and had the conference with Purcell. He gave me a yellow pad and said, “Why don’t you listen to my station for 24 hours, and if you hear anything wrong with it, jot it down for me.” I said, “Okay.” He came back on a Saturday morning and said, “Well, did you hear anything you’d like to change?” I gave him two yellow pads—the one he gave me all filled up and one I had to run down to the drug store in the hotel to get. He was terribly impressed

So he started reading my notes, and he said, “My God, if I did these things, the station would go broke.” And I said, “No, no, no, no, no. If you do these things, the station’s going to get rich.” Well, somehow or another, he had an amazing amount of confidence in me. Maybe it was because of the ratings I’d had in El Paso, or maybe it was because of what was then called the McClendon format. Anyway, I think they were billing something like a half a million dollars a year. In this time frame, that was a pretty successful radio station. I think they were rated sixth or seventh in the market at that time. So I said, “Now all of these things have to go.” Their morning show was a union program by and for union members of the electrical union. Then in the afternoon at four fifteen for fifteen minutes a day, they had the 7-Up sports report. I threw all those kinds of things off the air, and he said, “Oh my God, we’re billing $500,000 and you’re costing us $450,000.” And I said, “Yeah, but we’re going to double it,” being a smart-ass kid. And the fact of the matter is, we were number one in LA in three months. And we stayed there for as long as I was there, which was six years. The first year, they billed $960,000 or something like that. We were very close to a million dollars. And the second year, we billed $2.5 million. And again, you’ve go to put this in the time frame to appreciate it. I was there from 1958 to 1964, and back then, those numbers were astounding.

JV: How much of the LA audience did you have in those days?

Chuck: Well, I have something on my wall that my daughter saved to give me on my fiftieth birthday. It’s an old Hooper Rating. She had it all framed and so forth. Now you’ve got to remember, there were sixty stations there at the time. KFWB had a forty-two share. [Nope, not a typo here either!] The second station had a nineteen. The third station had a nine. And again, it’s nothing that will ever be repeated because it is impossible.

JV: Were you a hands-on production guy at this station as well?

Chuck: No. I was prohibited by the LA engineer’s union to do that. But there were two guys on the staff that were very, very good, and so I would write the things and sit there with both of them, and day after day after day turn out really, really good things. We created a lot of stuff. I had a woman with this wonderful Russian dialect and we called her Clara Voyant. Clara would read your horoscope every day.

JV: When and how did you get out of radio?

Chuck: I left radio wanting to go into television. I thought, everybody’s doing it, that’s where the superstars are, and that’s where I wanted to be. But I had an 18-month non-competition clause in my contract. I could not work in broadcasting in Los Angeles in any form for 18 months. They were paying me $45,000 a year back then, and as long as they continued to pay me, that contract was enforceable. So I was sitting here doing nothing. I learned to play golf. I was drawing a comic strip and things like that. Then one day, one of the guys from the radio station came to my home and said that they were about to lose the Rambler account. It was $45,000 a year to the station, they were about to lose it, and he said, “We need some kind of promotion.” I said, “I’ve been telling you guys in sales for a long time: you don’t need promotion, you need good commercials to get them down there for God’s sake. Don’t give away balloons. Tell them how good the car is, and they’ll come see it.” He said, “Okay, write a commercial for me.” And I said, “I don’t know how to write a commercial.” And he said, “Oh, sure you do. Go ahead and write one.”

Well, you may or may not remember, but people who were listening to the radio in those days remember a song called, Beep Beep. It was by a group called the Playmates. It was a song about a Rambler and a Cadillac having a race, and the song started out in a very slow tempo. By the time it was finished, the tempo was very fast. It was really a cute novelty record, and it was a big record. Well, I thought, boy a Rambler and a Cadillac, that’s a good idea. I might just make that song into a commercial. So I called the publisher of the song to ask him if I could use it in the commercial. Well, I hadn’t been out of the radio station long enough for the word to get around, I guess, to the song publishers. He thought, and I didn’t disabuse him of this, that I was calling from my lofty position at the radio station, and that I wanted to do something with one of his records. Well, back in those days when I was controlling that size market, they would do anything to get a record on the air. So the guy said, “Oh, go ahead, do whatever you want.” So I order a commercial based on Beep Beep and I called it Creep Creep, and it was a story about a girl who loved the Rambler, and every guy that didn’t have one, she called a Creep. That was basically the little story. So I recorded the thing with the Johnny Mann Singers imitating the Playmates, we put it on the air, and then I promptly forgot about it and went back to drawing my comic strip. About six weeks later I got a telegram congratulating me on winning the Advertising Association of the West top award, and I thought, well, hell, that was easy. I might think about doing this for a while. So I called Crowell-Collier, and having saved them a $45,000 account, asked them if I could do commercials. That certainly wasn’t competitive. And they said, sure, go ahead. So I started doing commercials for the remainder of my eighteen months. And by the time the eighteen months were over, my little commercial company was just bopping along so great I didn’t want to stop. I thought, I’ll do this for a couple of years and then I’ll see where I go from there. Well, here it is forty years later…oh God, that’s a long time.

JV: How have things changed in the commercial production world in your opinion?

Chuck: It’s changed so much. You asked me earlier about the quality of radio production today, and for the most part in the commercial world, it doesn’t even exist. Every now and then you’ll hear a produced or even semi-produced spot, but basically, you listen to the radio today—and I’m speaking of LA radio which is all I hear—the commercials are either live or they’re one guy reading over a music track, or it might be a two-voice thing, but certainly not well produced and not very funny when we try to be amusing, and that’s embarrassing sometimes. But for the most part, nobody is even trying to do it.

JV: Are you referring to the agency produced commercials as well as the local in-house produced commercials?

Chuck: Oh yeah. I’m talking about everything I hear on the radio. Of course there are still people like Dick Orkin doing neat stuff, but he, like me, is… well we’d be out of business today if we were having to depend on commercials. Somebody is going to read this and say, “Well, that’s bull, because I heard this great commercial yesterday.” Yes, we are talking about maybe ten percent of the stuff that you hear is really good. I’d even lower that percentage.

Now is the time to be on the radio, because anyone with any kind of quality is really going to stick out, and anyone that does anything memorable is really going to have people lined up at the door of whatever store they’re selling.

JV: You mentioned that many of the promos you hear on LA radio seem to be produced without any respect for the audience. Elaborate on this further.

Chuck: I think that that is the biggest crime going on today, that they’re not being created with the audience in mind. They are not saying, this is the reward for you. This is why it’s worth your time. This is why it’s going to be an entertaining experience. The best kinds of radio promotion I’m hearing today are the ones that are provocative and often on the talk stations. In a promo you hear one of the talk show people do something that’s outrageous, and you say, “Jesus, I better listen to that guy.”

JV: It sounds like you’re suggesting the basic concept of just letting the listener know what the benefit is to them.

Chuck: Well, it’s more than that. What if the benefit is that Rick Dees is funny, and maybe that is the total benefit. If the entire audience reward for listening to that station is that Rick Dees says something funny, or this particular talk host is provocative or incendiary or whatever he may be, if that’s the total reason, then fine. But it doesn’t do anything for the radio station itself. It tells you that Rick Dees is on in the morning and he’s funny, or this talk show host is especially provocative and you’ll enjoy him. But what is it doing for the radio station? I think that every chance you get, you should say, this is what this radio station is all about, this is why this radio station is great, this is what this radio station promises you.

JV: So not only express the benefit of listening to the morning show, but let’s give them a message that ties the radio station into the morning show?

Chuck: Not ties in. If I say, “Listen to Rick Dees and he’s on KISS radio,” that ties it in. What I’m saying is, where is the message about the radio station as a totality? I’m saying everything should be done with an attitude, with a personality that says this is what KISS is all about. And they don’t do that. They promote the guy. And I’m not holding KISS up as a station that’s doing terrible promotion because, as a matter of fact, they do what they do and they do it well. It’s just that they’re promoting individual parts of the station and ignoring what is the most powerful thing they have, and that’s the entire radio station. There shouldn’t ever be anything on the radio station that does not compliment the radio station, and that’s program content as well as promotional stuff. But the promotional stuff is where you have an opportunity to be very obvious about it.

Now in LA we also have K-ROCK and KPWR, and I think that they are the number one and two stations in the market at the moment. They both have an attitude about what they’re doing, and it is more of a station attitude than exists on the majority of the other stations. But I still think it could be there a little more constantly.

The station has to identify first what the station is; not what the morning show is or what a performer is, but what is the station. This is what we are. This is how we want to promote that. This is how we want people to feel about the station. And that’s another thing: there is not a cerebral answer to this. It is creating a feeling about the station. Everything you do should create an affirmative, emotional response to the station. It’s far more important what people feel about what you’re doing than what they think about it because they don’t think about it. Or rarely do they. And if you ask them what they think about it, they’re going tell you what they feel. They’ll say, “Oh, I like that guy.” Well, that’s how you feel about it rather than any cerebral reason for listening. So what you have to do is define the personality of the station. What is the feeling of the station? Decide what you want to communicate to the audience and then do it constantly. Every time the call letters are mentioned, they should be done with that attitude or personality, I think.

JV: So on our morning show promo, you’re suggesting coming out with this attitude that says, “Here we are, we’re this great radio station, and here’s a taste of the morning show that’s part of us.”

Chuck: That’s exactly right.

JV: When did you get into working with kids on your commercials?

JV: When did you get into working with kids on your commercials?

Chuck: When I got into the advertising world, one of the very first agencies I worked for was Doyle Dayne Burnbach, and they were the most creative agency going in those days. There was a potato chip called Laura Scudder’s, and they had the line, “the noisiest chip in the world.” They wanted to use that on the radio because they wanted to create this big noise of someone biting into a Laura Scudder potato chip and how it was so crispy and crackly and all that sort of thing. So they said, go ahead and let’s see what you come up with.” Well, I thought, “the noisiest chip in the world…” Who would really say that other than an announcer reading the advertising slogan? I thought, well, maybe a kid might. If you say, “How do you like that?” They say, “It’s noisy.” And so I began. I said, “I will put that line in the kid’s mouth,” and as soon as I said that, I realized I was going to have to put the potato chips in those kids’ mouths too. And so the very first kid spot I ever wrote was with this one little boy saying, “Guess what I got in my mouth.” And a little girl says, “I have no idea what you have in your mouth.” He said, “I’ll give you a hint, it makes a lot of noise.” And she says, “A fire engine?” And so forth until you find out it’s a Laura Scudder potato chip.

JV: Did you find these kids easy to direct?

Chuck: Yes, they were so easy to direct. I could get exactly the inflection I wanted out of kids because all they did was imitate what I said in exactly the way I said it. Now, if you did that to a full-grown actor, he would be affronted…you know, “You’re giving me line readings?” and that sort of thing. And he would have a point too because the first thing you want to do when you have an accomplished actor in there is hear what the accomplished actor can do with the words. He may do something, and often times he does, that you don’t even think about…and you wrote the damn stuff.

But kids are more easily directed. All the kids I ever used were between four and seven. And the reason for that was, that’s when they are the most charming with the way their little mouths shape those words. That’s when you can put that dumb honestly into their mouths, which people find charming. And the other thing is, once they learn to read at school, then boom, they’ve lost the ability to parrot the way they hear the words. And I don’t know why that is.

JV: It sounds like the same problem we have with many adults in the studio. You want them to read a script and sound like they’re not reading, but they sound like they’re reading anyway.

Chuck: Well here’s a tip for whoever is reading, and it’s so simple. Whenever you have a piece of copy being read by someone, and you want them to sound real… And first of all, it’s got to be on the paper. I mean, you’ve got to write it in real language. You can’t expect to use the word “quality” every third line and have it come out like somebody’s not trying to sell you something. So you have the copy, the guy’s reading it, and it isn’t as real as you want. Have him look at the first two lines and commit them to memory. He doesn’t have to remember it for over ten seconds, but have him know what those first two lines are. Then stand right in front of him and say, “Look me in the eye and tell me that.” And that’s all you’ve got to do. It’s so different it’ll shock you. Just have him look you in the eye instead of looking at the paper. And don’t be too critical if he changes a word here and there as long as the meaning is there.

If I look back on my career at what I’m most proud of, it would probably be all the “Reach Out and Touch Someone” spots I did. We did those things for six years, and we did oh so many of them. And reality was what those spots were all about. Obviously they were all written, but the talent was never looking at her script when those things were recorded. Interestingly enough too, one of the talents, the caller, was always recorded on a real telephone. The other one, the recipient of the call, was recorded with just a straight microphone. Today—and technically it probably does sound a little better—whenever you hear a spot where someone’s supposed to be on the telephone, the producers are using a filter and recording them on a mike.

JV: Tell us about your new library, Chuck’s Kids. What is it and how did it come to be?

Chuck: A couple of years back, when the advertising agencies really started staying in-house for all their creative and farming out only the production work, our business dropped way off; and having done this for such a long time, I thought maybe it’s time to back off and make all this stuff work for me. So I called a very good friend, Lee Larson at Clear Channel, and talked to him about the viability of maybe selling my scripts, which number in the thousands. He suggested that while RAB had a book of scripts and even Clear Channel has a book of scripts, while they might not be the quality of mine, which was a very nice thing for him to say, he said, “Yours would be a third source.” And he said, “Beside that, to me, what made your commercials so outstanding in addition to the writing was the performance and the production.” And I got to thinking about that and wondered how I could make that available to stations that would be interested. Going through the stuff in the library, I found out pretty soon that there was not a good way to do that because all the spots were written from an advertiser point of view back then, and they were all kind of oriented to the price of the product or whatever it was we were selling…except for the kids. With the kids, we determined very early on not to put commercial lines in their mouth because that would not be honest. And the naivety of kids saying, “You’ve got a lot of good stuff here,” rather than saying, “Do you have the latest edition of…” whatever, came off so much better.

Anyway, the Kids library seemed to be perfect because we could take out the commercials, and the vitality, the heart of the spot still existed. And these kids were so darn good that it just made everything really appealing. So we went through these things and there were hundreds of them. Now most of them, for one reason or another, were kind of connected to the product, but the ones that stood alone in this beautiful generic form are the ones that made it to the Chuck’s Kids Library. We’re going to put them out in three editions. Edition #1 has twelve completely generic spots, and then it has three spots that are financially oriented, three spots that are food oriented, and there’s one other category. And also within that will be the original spots so that they can hear them and get ideas for performance or even copy. And then there will be tips from me on how to write for these in a kid situation and even how to direct the talent and so on. So all of that’s in this package that we’re going to offer to the radio station. They can put a spot together very quickly in the radio station by inserting one of the local announcer’s voices in there, and you’ll end up with a very, very nice spot to take out to a client who has been hesitant to go on the radio or whatever. You’ll be able to play a spot for him with his name in it that is so charming. It should make local sales a lot easier and make the radio station sound better because it’ll have these wonderful kids’ spots on. Although, even as part of the package, I am suggesting that no more than two clients at one time should be on the air at the same time because you don’t want to turn your radio station into the kids’ station. But, nonetheless, when people hear one of the kids’ spots, because they’re so darn charming, they’ll turn the darn thing up, which is always a good thing for a radio station, most especially for commercials. Also as part of the package there will be like twenty-five or so absolutely wild lines. A competent writer could look at that list of lines and say, “I got five more spots right here.”

JV: When will the library be available?

Chuck: Almost now. We’re just doing the last parts of it. The actual kids’ spots are all done. They’ve been run through these marvelous machines that make them all sound like they were recorded last Thursday.

JV: What advice would you give programmers and producers today?

Chuck: It seems to me that there is much too much of a totally cerebral approach to both programming and production today, and that may have to do with the bottom line mentality. But even within that, I think it would be totally possible to listen to your radio station more with your heart than with your head. What I’m saying there is how does that station make you feel? You, the Program Director, have to be the number one fan, and if you’re not, then you’re doing something wrong. Because if you don’t like what you hear, the chances are that other people are not going to like it either. And if you don’t like what went wrong, well you’re probably the only one in the world that can change it.

And the same thing goes for the production. Anybody can make a spot that says, “It all happens Friday at 7:30…” with some kind of a drop-in and maybe a music track. That’s easy to do. Everybody can do that. Everybody does that. But one more time I would say, do you like it? Not, do you think it works, but do you like it? Do you like it with your heart as well as your head? Is it something that you didn’t do yesterday? I think that people tend to get into habits, and habits can absolutely ossify creativity; and the only real sin, I think, is not to be creative. If you do it today like you did it yesterday, then there’s a good chance that a whole bunch of your audience is going to hear it today like they heard it yesterday, only this time it won’t be fresh, and so this time they’re going to ignore it.

And when I say, do you like it, I don’t mean, does it make you laugh, does it make you smile. Even the drama of something as terrible as a bus load of kids getting hurt or something like that, when you do it well, there’s something inside you that goes, “yeah.” And that’s what you’re looking for every time.