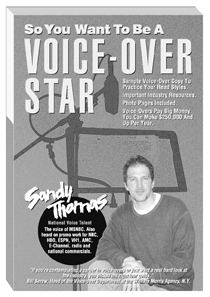

Sandy Thomas, Voice Talent, New York, NY

So You Want To Be A Voice-Over Star. That’s the title of a new book by Sandy Thomas, a former radio production guy who decided to go for it all the way, and made it. It’s been ten years since we touched base with Sandy. At the time he was just getting his free-lance voice business underway, and was off to a good start. In the past ten years, Sandy has built a voice-over career that many of us dream about. He had no special connections and no “voice of God.” He just had a love for voice-over and a desire to make it work. His new book, So You Want To Be A Voice-Over Star, details the things Sandy learned along the way and provides a path for those that wish to do the same. This month’s interview gets a sneak peak at the book and some very frank feedback from a very successful voice talent that came up from the realm of radio production.

JV: When we last interviewed you in 1989, you had only been in radio a few years and had just started your free-lance business in Miami. Did you stay in radio for a while before going out on your own?

Sandy: I did. I was in radio down there from ’86 all the way through ’93. At the time we did the interview, I was at an AC station that was an aggressively imaged radio station and then moved on in that market to Zeta 4 and then to an AC, Love 94, which really enabled me to focus on which direction I wanted to go in. I was offered a unique opportunity there. They had a big 8-track facility in their radio station, and I was offered the chance to run that studio. Basically, my only responsibilities were to image the radio station and run this studio to create some kind of profit center. They were just hoping to break even on my salary. I prospered in this studio, built a free-lance career, and worked out of the studio from ’88 to ’93.

JV: How did you set up this business inside a business?

Sandy: I would bill hourly for the studio. Anything I did in that studio for myself—for instance if it was for a local car dealer, an outside account, and they wanted to come in and do a spot there and have me engineer it and perhaps voice it—I would charge them a certain hourly rate. At the time it was sixty dollars an hour for the studio, and that would be billed from the studio. It was just like a full-service audio studio within the radio station environment. It was called Studio 94, and I was the general manager of that. I had no commercial production responsibilities, no dubbing and no trafficking responsibilities at all. The only commercial work I would do would be if an account executive needed my help with voicing and writing. And only if I had the time would I lend my talents to their sales department. Other than that, my only production responsibility was imaging one of the stations—at the time they owned three. So it was great, and it enabled me to pretty much just pound away at the voice work and learn the managerial end of running your own production company and pursuing a free-lance voice career. It was a great opportunity for me, and it was very difficult to leave, too, because when I left, I was doing really well.

JV: Why did you leave this comfy situation?

Sandy: I always wanted to do national commercials and always aspired to be a national voice talent, doing national commercials, movie trailers, and whatever else you would consider in a national arena, working with national agencies and so on. Well, working in a small market, being outside the major markets like New York, LA and Chicago, doesn’t really give you the access you need to be able to build a career. Not to say that it can’t be done because there are guys outside those markets who do get the national business, but I just felt that if I ever really wanted to do this full-time and make a go of it nationally, I would have to relocate to a market that had a lot of those national agencies located there, a market where most of that work goes on. And most of it goes on in New York, LA and Chicago, with some of it going on in other markets like Dallas and Minneapolis and San Francisco, cities like that.

So in the winter of ’92 I sent a tape to an agent in New York. I didn’t send it to Chicago or LA because I’m from New York. I was raised in New York, and this was where I wanted to be if I was going to do it. Sending the tape was really inspired by somebody else who came into my studio and said, “Hey, I’m going to New York. Do you have any addresses of agents?” After giving them to her, I said, “You know, let me send a tape up to a couple and see if I get any response.” So this is for all the guys and women out there who think that you have to know somebody to get an agent. I just sent a tape. I didn’t know anybody, didn’t make any phone calls, and got a call back from Cunningham Escott Dipene in New York. Cunningham Escott Dipene is probably, I would say, one of the top three voice-over agents in the world. They just have an awesome amount of talent, both male and female. If I gave you the names and played their commercials for you, you would say in a second, “Oh man, that’s that guy” and “I’ve heard that guy.” So they asked me to fly up there, and I did.

JV: And getting an agent was that simple?

Sandy: They don’t automatically sign you. They’ll just tell you they like your tape and will ask when you’re coming to New York. I flew up and had a nice interview. There’s usually three or four agents within an agency who handle the voice-over department. The way the New York agents are made up—or LA and Chicago—they have different divisions. There’s modeling, acting, legit, and there’s voice-overs. It’s a separate division, and usually there are from three to five agents within a voice-over department. So I went through the interview process. They liked my sound, and they had a need in their roster of talent for my type of voice. I signed with them, but I did not go up to New York until that following spring. They asked when I was coming, but at the time, I had no plans to move to New York. I was going to try to make a go at it from Florida because I had such a great job down there. I was pretty much coming and going as I pleased, had my own studio, and wasn’t paying any rent. It was a great situation.

JV: Was eventually moving to New York part of the deal if they signed you?

Sandy: No. I really think they had a need for my type of voice because they were very aggressive in wanting to sign me. I don’t think they had that type of voice at that time or maybe not enough of them, and they wanted me to be in New York because you really need to be there to really get it going. But I told them my situation, about this studio, how I had access to equipment, how I could send auditions overnight, and they said fine. If you feel that strongly about staying in the state of Florida, we’ll work with you from there.

About six month’s later I said, “What the hell; let’s give it a shot,” and pretty much gave everything up to do this. I had family in New York, so I wasn’t taking a risk in the sense that I had nobody to lean on. At that time, I was 29. I had some money saved, but I had to give. I had to quit my radio job obviously, and I pretty much had to lose all my accounts. I only had six or seven radio stations that I was doing some imaging work for at that time, so I didn’t even have a roster of radio clients to give me what you could consider a salary you could survive on. I brought some of that work to New York, but for the most part, I had to give up everything I was doing in Miami to take a chance and, hopefully, have this thing work in New York. I rented a house with a couple of friends, and set up my studio in the house. That was the first studio that was my own.

JV: Quit the radio station, dump most of your accounts, move to New York, build a studio, and move in with some friends. That sounds like college stuff there!

Sandy: It was, fighting through the beer bottles and hollering, “Hey guys, keep it down; we’re recording up here!” It was great actually. We had a nice house in Bellmore on the water. There were three guys, so we were able to afford it. They would work in the daytime, which left me alone to do all of my recording in the daytime. By the time they got home, I was done.

JV: How did you equip the studio?

Sandy: It’s just an 8-track digital studio. I started with a Korg SoundLink, which I still have, and I’m still using. It’s fine. At the time, my priority was to be a voice talent. That’s what I am. I do production, and that’s what I came from. But I figured, at a certain point, you have to decide what you want to do, and for me, to try to do it all just breeds mediocrity. Maybe other guys can do it, but in my case, I put all my efforts into my voice, building my national career and solidifying myself in New York. I pretty much suspended any real thoughts of trying to be a guy like Jeff Thomas or Eric Chase. I knew at that point I could do production. I knew I had the instincts to do it. I knew that if I wanted to really go there, I could do it, but I decided voice work is what I wanted to do. I’ll do production for a couple of stations here and there, just to keep at it a little bit, but I’m going to be a voice talent. That’s what I do. You could do production in my studio, and I do; but for me, it’s just a tool to record my voice.

I’ve got some outboard EQs, which I really don’t use because every guy wants it flat with no compression and no EQ. I’ll use a little of it when I do stuff with Jeff [Thomas] and these guys who want a little compression. I’ll tweak it a little bit here and there, but for the most part, I send it down to the kitchen and let the chefs mix it up. For the mic, I’ve got an old Neumann 1000. I use a Bryston pre-amp with the Summit SL100C console, which was cutting edge back in ’93.

JV: So you moved to New York and got an agent. How did it all start happening for you?

Sandy: I started going out and auditioning daily. The process in New York is everybody wants to hear what you sound like, and what you sound like doing their stuff. Even the guys who have been here for years still have to go out and read. So I just began to go out and audition and experienced a lot of success my first year here. I got very lucky and signed some big accounts—some double-scale. One of the first accounts I got was for Stouffer Hotels. They were doing a big national casting, looking for the national voice of Stouffer Hotels. At the time, they were spending lots of money in advertising. I actually haven’t heard them on the air for a while. I got this account, and it was paying double-scale on network TV. That is like the equivalent of playing in the World Series, bottom of the ninth down by one, and hitting the home run to win the game. In scale voice-overs, you can’t really get any higher than double-scale. To get something booked at double scale on network TV, that’s it. Now if you’re a celebrity, you’re in a different category. Now they’re paying you for your celebrity status.

JV: Do you mind telling us what that account paid you?

Sandy: That probably paid me $60,000-$70,000 a year.

JV: Wow! And this was your first major account?

Sandy: That was my first major account, but I haven’t struck one of those double-scales again. I’ve got some nice accounts though, and I’ve been very lucky. I don’t know what it is. I don’t think I’ve got a great voice. I’m just a guy who was raised in New York, who overcame a lot of regionalisms in his voice. But I don’t have a voice like James Earl Jones where he walks in a room and everybody stops. The guy is unbelievable. I think the gift I have is just a realness, which I think is what a lot of guys are doing today.

I’m a scale voice guy, which means I get scale, whatever the union scale is. Your agent can then negotiate above that point, whatever she wants, but you have to at least make the scale because that’s what the union dictates. You do maybe one or two spots at scale on network TV, and you can make twenty, thirty, forty thousand dollars, and it will take you half an hour. You go in there and do that spot, and it runs for a year, maybe two. You’ll make thirty or forty grand in residuals a year. And if they use it again, for the second year, they’ve got to pay you. And you don’t even have to go in to re-record it because they have it from the last time.

JV: What came next? Did you start doing a lot of commercial voice-over and imaging a lot of radio stations again?

Sandy: Actually, that first year, a lot of the business was commercials. But I also did the launch of ESPN2, and I launched MSNBC, which I am still the national voice of. And that first year of ’93, I did a lot of commercials, too. I would say that sixty to seventy percent was commercials. But as soon as I got MSNBC, which was the summer of ’96, and became the voice of that network, that put me in a situation where I ended up being in my studio a lot. I did two sessions a day, one at eleven and one at four-thirty for an hour. Getting that account, once again, was like the equivalent of that home run, a once in a career kind of thing. You know, any guy dreams of getting an account like that, which pays you all that money for two hours a day. But you’re not counting the years it took you to get to the point where you’re able to do that. That’s not seen. “Man, you make that much money and spend only two hours a day doing it, and you don’t even have to leave home. You do it out of your home studio!” People constantly say that to me, people I work with or interact with. “How do I get a job like that?” But they don’t see that seven or eight years you labored back then, where you weren’t making that money and you were in studios every day, not getting paid, trying to develop your voice and the dynamics of your voice, practicing and not getting paid—unless you’re lucky enough to just fall right into it, have some kind of gift and not have to really prepare or do anything.

But getting back to your question, at this point, I would say I’m probably doing about eighty percent promo work, network promos and radio stations. I voice about forty-two stations, MSNBC, and about four local TV affiliates. I voice WXIA in Atlanta. I voice a lot of stuff for HBO. I’m doing a session tomorrow for ESPN. And what happens when you get into that promo world, you end up getting all your time dominated, and the problem is, that hurts your commercial side because you’re not able to get out and audition. It’s like a double-edged sword. You’ve got to get out and audition to get the work, but when you get the work, you can’t get out and get any more work.

My time is so dominated now that I can’t get out and get any new work, and they will not let you audition by sending your voice on tape. It’s very rare that they do. You’ve got to be there. The problem with me is that it’s an hour and a half commute into Manhattan driving, or forty-five minutes if I take the train. But I’m booked every day, so I don’t have a block of time to get in there.

JV: Well you’re pretty established there; can’t you just record the material for the audition at your home studio and FedEx or ISDN it to the people?

Sandy: When they can fax me something, I can audition. But this is rare. Here’s the way it works. A casting agent calls your agent and says, “I’m looking for a voice for Miller beer. This is the description of the voice.” Now my agent says, “Sandy would be great for that, but he can’t ever get out. Can he send you his voice?” They won’t do it because they will not give up their script. They will not send their scripts to talent. So you have to almost go to where the source is, whether it be the casting agent or an advertising agency, or sometimes they will send the script to your agent. In those cases, you can work out situations where you can do it from your studio. My problem is that I’m working, and nobody feels sorry for you when you’re working. You might say, “Hey, I want to build my commercial side because I haven’t been doing any commercials.” Well, you’ve got to give up something else. “Well, I don’t want to give anything up. I’m making money, and I’m doing well.” It’s not natural to erode your business. It’s not a healthy thing unless you feel that you want to take that risk and give it up. For me, as long as I’m working and I enjoy it, then that’s fine. So for right now, my career has kind of shifted more to promos.

JV: When did the idea for the book come around, and what made you decide to write a book in the first place?

JV: When did the idea for the book come around, and what made you decide to write a book in the first place?

Sandy: The idea has actually been around for the last few years. The information has been in a word processor for two years, and I’ve just worked at it when I had the time. I finally decided I just wanted to close it out and finish it. I felt I had a decent amount of information at this point to share.

There were a lot of unexpected situations that came up along the way in my career that I felt I could pass along to other people who want to do this, things they could probably avoid if they knew about it beforehand. They should give some kind of orientation to people who get into voice-overs, something to let them know what they’re going to confront, what they’re going to deal with, how to handle different situations, how you pull along thinking you’re going to get something then have it taken away from you. Opportunities that you think you’re going to get can be taken away so quickly, and that’s the nature of the business. Along with the success stories I mentioned, there is another side. I won’t call it the evil side, but it really requires a certain state of mind to be able to survive in this type of business.

I think one of the healthy mindsets is to always be in a forward motion—always, all the time. Always looking forward because there are so many rejections. There are so many disappointments. There are so many “what ifs.” There are so many “what could have beens.” It can actually contribute to so much negativity that it can dismantle you. So the way to really approach this business is going forward. Do an audition. Forget about it. It’s over. Don’t even think about it or ponder it. Don’t even wonder if you’re going to get it.

Let me give you an example. I did a session for ESPN. The audition came in from my agent and I was like, “Oh, wow, ESPN! I did a bunch of stuff when I first got here for ESPN!” For a while after that there was no activity because I wasn’t able to get out and audition. Then this audition comes up, and I said to myself, “There’s no way. I won’t get this.” In my mind, just for a second, it crept in. I read the audition and sent it out. I didn’t even think about it after that. I booked the account.

So just when you think you know something, you don’t know it. You’re so far from it that it’s really not even worth thinking about it. It’s almost like you should just be performance driven, and that’s it, almost emotionless because this is really fictional. It’s just a business. It’s just your voice sitting on a commercial, sitting on a promo that’s going to be replaced someday. It might be ongoing, but that’s depending on so many things that are out of your control that it’s not even worth worrying about it. You just need to worry about the next audition and performing, and that’s it. You can’t think about “am I going to get this account? When am I going to lose this account? When is this station going to drop me? When is MSNBC going to drop me?” I make so much money from MSNBC, almost two hundred thousand dollars. Am I going to lose this account in two years? How will I support my family? I can’t go there. But each year, I make more money than the last.

You’ve got to look at things as a career and not in the short term. The short term is, “Will KIIS-FM in LA sign me next year?” That’s the short term way to look at it. My contract with KIIS actually comes up this December. I don’t even think about whether or not they’re going to sign me. I don’t even care. I mean, it would be nice, and I hope they do, but if Jeff calls me and tells me they’re going to go another direction, “No problem, guys. Here’s the termination agreement. You need to sign it and get it back to me.” Because you know what I’m thinking? That I’ll get on another station in LA. Now, I won’t be on KIIS any more, and I’m not going to have that prestige. But you know what I’m thinking? “I’ll see you guys across the street somewhere else.” It’s so pro-active to be that way than to be worried. And if you can do that, then you’re bulletproof. Then you go into sessions with confidence. You go in reading with more confidence because you don’t care. You don’t even care if you get it. It’s like you’re just going in to perform. You care about that. You love it so much because you’re performing. Obviously, you want to get paid, but the priority is—the priority needs to be—that you love it and you want to perform. And if you get it, then great. And if not, then you can’t control it anyway.

JV: What else can the reader look to get out of the book?

Sandy: How to get an agent, how to deal with getting an agent, the preparation that it takes to take your career to the next level. You know, being in radio and reading commercials on a radio station is a totally different world than reading in a free-lance, voice-over environment. Even doing local agency work is totally different than doing radio voice-overs. In fact, if you’re doing work for agencies, commercial voice-overs, and you’ve got some kind of connection with radio, it’s like a negative stigma attached to you. You don’t even want to tell people you’re from radio at all because guys who are in radio collectively are looked upon as guys who don’t really know how to read.

This book, for most practical purposes, gives you insight into reading copy and into getting a mindset to be able to interpret copy to make you marketable, to make people want to hire you. It gives you techniques on what to do to get yourself to that level where you are desirable and marketable. It’s also a great information source. It lists a lot of places to get information on what agents to send your tapes to. It gives you a lot of information on where to go on the web for information on getting work, where to send your stuff, how to get training, where to get training, how to get a teacher. It talks about the process of getting some training because it’s just like playing golf. If you go out on the golf course and you have some athletic ability, chances are you might make contact with the ball once in a while. If you don’t have any athletic ability, you’re not going to make any contact. But to have consistency, you’re going to have to take lessons. Right? If you want to be a doctor, you have to go to medical school. Voice-over is no different. If you think that just because you have a good voice you can read, that you’re going to be able to get into a voice-over session and be successful, you’re dreaming. You can’t. You have to have some concrete training because there will be some situations that you don’t even know about.

As an example, let’s just say you could read. Let’s just say you were a guy who could interpret copy. Are you able to get into an environment where you’re not going to be nervous? And you’re going to get into that environment. There are going to be people in a control room. There’s going to be an engineer. There’s going to be a studio producer. Possibly the client is going to be there. You’re going to be all by yourself in a room in complete silence. And in voice-overs, when you get into the free-lance environment, they don’t use music to kind of drown out the little nervousness you might have in your voice. It’s just you reading. And most times, when you’re doing sessions in New York on a national level, or even locally like in small or medium markets, you read with no music. They want your voice. Then they want to post your voice. So the book teaches you about training, where to go and how to scrutinize the people you are possibly going to get training from, what to look for in that person whether it be a woman or a man.

The book is like a story of a guy who has a mediocre voice, who actually could not even get hired by his college radio station—which is true—a guy who took what little talent he had and harnessed it, and step by step, built a very successful career. This is how he did it; you can do it to! This is an example of how a guy who had no experience, didn’t know anybody, and didn’t have any connections, built a successful voice-over career.

JV: Is the book targeted just to people in radio?

Sandy: No. It also gives the person not from radio direction on what they need to do, whether they are a plumber who wants another career or a person contemplating a career in voice-overs, a young kid who is eighteen and says, “Maybe I want to do that.” Well, this is what you need to do. These are the different steps you need to take. And then it gives you resource information to go ahead and do that.

There is also practice copy in this book. I’ve formulated a chapter on it that gives you national copy to work with, not just copy from a local car dealership, but different samples of national copy that you can actually take and record and play back and listen to what you sound like and how far away you are from getting to that point where someone will pay you, although that wasn’t the goal for me. And I hope it isn’t your goal either. I hope you do something because you love to do it, because in this business you need to love to do it. You should not get into this business for any other reason because I don’t think you’ll be successful at it unless you really enjoy it because it will emanate from your voice. If you hate what you do, it will sound like you hate what you do, and you won’t be marketable unless you’re hired to be an angry asshole. But hopefully you’ll get into it because you want to do something you enjoy, and you’ll take the right steps to get the training to make yourself marketable. Then you’ll be able to either supplement your income or make a good living doing it.

JV: What are some other topics covered in the book?

Sandy: It covers a ton of stuff: Do I Need To Have A Naturally Deep Voice? How Do I Get Started? Do I Need An Agent? Should I Make A Demo? Broadcasting School, Training, Interpreting Copy, Being Natural Sounding On Mike, Romancing Copy, Terminology, Rejection. It talks about the emotion of rejection, which really is an important thing. What Are My Chances? The Sweeper Business—it goes into imaging. Obviously, that’s where I come from, so I’m comfortable there. Being a union voice talent as opposed to being a non-union voice talent. Finding My Money Read, Making A Demo, Getting Work, Auditioning, Negotiating A Big-Time Contract, Keeping The Humor—that gets back to the psychology of this business, which is so important. I can’t stress that enough. It’s almost like the stock market. You’re up. You’re down. You’re up. You’re down. You got it. You lost it. You got a nice account. You lost the account. You’re up for an account. They decide to go for another voice. You’re constantly on this barometer, and you’ve got to really look at it in terms of twenty years instead of six months or a month or a week. Forget about the week. Look back on the last ten years. Then go, “Hey, pretty decent career,” if that’s your thing. Other topics include: The Script, My Attitude, It’s a Small Business, My Agent, Marketing Myself.

JV: Is the book focused mainly on getting voice-over work in New York, or can people in other markets and smaller markets benefit from reading it as well?

Sandy: It talks about voice-over in other markets, what you need to do to make some extra bucks working right in your market, what you should charge for a spot. In a small market, you have to look at your voice career as your ability to be like a one-man advertising agency. In a smaller market, I would set myself up as a one-man ad agency. I can come to you, the client, and I can take what you’re doing right now and show you how I can do it better for you. I can maximize your results. “Here, Mr. Advertiser, look what you’re running right now.” Boom, press the tape. “Now let me show you how my emotions will make you really listen to the message, and you will relate more to my message or be more inclined to be motivated by what I can do in the way I read. See this guy over here, he’s just reading because he’s at this radio station all day. He’s getting ten scripts. You’re number nine, and he’s at the end of his day.” “Why you, Sandy?” “Because I know how to read better. I know how to read copy. These guys are announcers. They’re at a radio station. They’re not taught. They’re not specialists. If you have coronary disease, do you go to a doctor or do you go to a cardiologist? When you want a voice-over, when you want a commercial, you go to a free-lance voice guy and you have your message done by someone who specializes just in that.”

That’s how I was successful in South Florida, because I was a specialist. Everybody else sounded like a guy from radio. Then I came along, and I knew I had that sound because I was able to read. And what that sound is really is just emotion. It’s almost like when you meet somebody and have a conversation and you get a closeness; you’ve really talked about something. Then you talk to another guy, and it’s just small talk bullshit. There’s no connection there. Voice-over is no different. When I’m reading a promo or a commercial, I’m always trying to make a connection with whoever is listening. I’m not talking romantically, but some kind of connection where you hear it and it grabs you. I don’t think many guys think like that when they read a commercial. In fact, I don’t think ninety percent of guys in radio even think like that. I think they see the copy and read, you know, “Come into Don’s Florist for $4.95 specials.”

JV: You mentioned, “what you should charge for a spot.” If you’re union, working for scale, that’s pretty much decided. You must be referring to non-union talent.

Sandy: Right. In a lot of training, they won’t tell you what you should charge. That won’t be part of the curriculum. If I were teaching a class, it would be. When I took my training in Florida, they didn’t give us that information. My book gives a framework for non-union guys, what they should charge. It acquaints him with usage. A lot of guys might charge $150 for a voice-over that’s going to run on a network and think that’s fine. They might charge $500 for a national spot. If you’re running that commercial on a national network, you’d get screwed if you charged around the union scale for a local spot.

I just told you what I’d get for a network commercial, like thirty grand. I did a commercial that’s running right now for Payday. I’m only telling you this to make a point. Believe me, money don’t make the man. It’s going on two years now. All I did was, “The new Payday. Twenty percent more caramel,” or chewy peanuts, or something like that. I have made thirty thousand dollars from that commercial already this year. That commercial took me five minutes. Five minutes. Now, I come to you—five hundred bucks, thirteen weeks. Think how much I’m taking advantage of you to run that on network TV, and I didn’t have to pay your pension and health. I don’t have to pay anything beyond that, no residual payments, no reuse fees, nothing. That is worse than what Kathy Lee Gifford supposedly did to the sweatshop workers in a third world country.

So, my book goes into a chapter for non-union guys and gives them a framework to set up their rates and acquaint them with that. Now, granted, if you’re not a union talent, you don’t deserve to get that wage, but you should get somewhere in the ballpark. If it’s going to be running on national network, you should be charging two thousand dollars, or at least a grand, maybe three grand. The book gets into this. What should you charge for a local spot in radio? $150. I think that’s a little less than scale. I think scale is $167. It talks about what you should charge for a TV spot. $300. Is the client going to run the spot on a network? If he is, then you should charge him this. So the book gives guys that opportunity to get acquainted with a national voice talent who’s successful, who’s done it all pretty much. Maybe they think, “I have no relation to this book because I’m not going to New York. I’d like to just start a local free-lance voice career. I’d be happy making an extra five or ten grand a year.” It gets into stuff for that guy.

JV: Aside from reading your book, what other advice would you give someone wanting to get started in the voice-over business?

Sandy: Go get a great teacher to align yourself with. Expect to invest about two thousand dollars for a good teacher and get involved in good course work because you need to get yourself into a situation where you are tested. And the only way you’re going to be battle tested is to be in a classroom environment because they will take you into a studio and test you. If you’re in a class curriculum, probably about sixteen hours, you will get yourself into a recording environment and will be battle tested. After that curriculum is over, the teacher should tell you you’re ready. If you’re not assessed in that way, and you get yourself out into a situation where you’re not ready, you will only get one chance to make an impression. The word will travel very fast. That’s why it is so important that you are ready to go out in that creative environment when you’re ready and not any time sooner. Because if you get out in a studio in an agency, and say you’ve got a good voice and for whatever reason you were able to put together a great tape, let’s just say you’re lucky enough, what will happen when you get into the studio? Say you freak out. You get the headphones on and you just freak out. You get nervous, and you know how it is when you get nervous. The air starts pumping, and you can’t read. You don’t have the oxygen, and you can’t breathe right. So you fold, and you can’t do it. What’s going to happen? That agency’s going to say, “Remember this guy? Man, he had a good tape, but we had him in a session and he trembled.” “Really?” “Yeah, he was awful. Forget that guy.”

So you’ve got my book. You’ve got a lot of great information. Now you’re going to get yourself a teacher. You’re going to spend a little money and get yourself a great teacher and get that training. Then at that point, you’re going to know. Then at that point you’ll either be able to go and market yourself and get work, or that teacher’s going to tell you it’s not the right thing for you or you don’t have the talent to do it. But I think everybody who has a voice can do voice-overs…everybody.