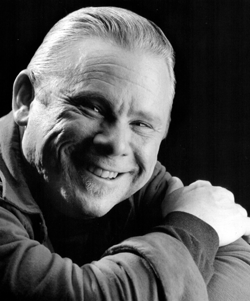

Tom Richards, B101.1/WBEB-FM, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

by Jerry Vigil

by Jerry Vigil

There’s no denying that some of the most stimulating production comes from today’s somewhat “unrestrained” formats like Rock, CHR, and even News/Talk, but if any format is going to win, top-notch production has got to be part of the formula. For Philadelphia’s A/C giant, B101.1/WBEB-FM, the importance of production was never a question—not when it came to equipment, and not when it came to personnel. With over 20 years in radio, WBEB Production Director Tom Richards has been keeping the station on top of its production game for the past seven years. He has been the voice for hundreds of radio commercials, narrations, and industrial presentations with clients such as Chancellor Marketing Group, Panasonic, Honeywell, Ensoniq, Smith-Kline Beecham, and Seiko. He also narrates “First Flights with Neil Armstrong” on cable’s History Channel. Like the station itself, Tom has won numerous awards including AIR Awards from the March of Dimes and “Best Major Market Radio Commercial” from the Pennsylvania Association of Broadcasters for three of the last five years. Sit back for an informative chat with Tom, and be sure to check out Tom’s demo on The Cassette for a taste of A/C production at its best.

JV: Tell us about your background in radio.

Tom: I went to Syracuse University in 1969 as a freshman, and I intended to be an English major. While I was there, I realized that the guys I hung out with were studying to be radio guys, and this was a totally new idea to me. I never realized that maybe I could have a career in radio. So I tried out for the radio station on campus, WAER, 88.3, and I got a job as a student DJ which, of course, didn’t pay any money, but it gave us free rein at the radio station. And we had a blast. We would sit around the dorm after hours, when we should have been doing school work, listening to records and comparing this guitar player with that guitar player, and this group with that group, and figuring out the perfect segue from one song to another. This was in the sixties, the height of underground radio, progressive radio, and I was just loving it. That’s where I got bitten.

JV: You spent most of your time in Philadelphia, is that correct?

Tom: The last twenty years. In 1979 I came to Magic 103, WMGK as the evening jock from WMGX in Portland, Maine. I stayed at Magic for eight years then was let go. That was the first time I’d been blown out. They had fallen on rough times. I was the assistant PD at the time, and they were looking to bring in a high-priced morning talent. Myself and three other guys were cut from the payroll to pay for this guy. So there I was, kind of out there thinking that I could slide into a PD job somewhere, but that didn’t happen. So I did an Oldies show on KISS 100 in Philly for a while—now it’s Y100. I also did some archive work for WPEN, the Big Band station in town. I carted up their entire library, which was a real musical education for me. I kicked around some things—tried radio sales for a little while and that didn’t work. Then I worked at Donnelley Directory’s Talking Yellow Pages for a while. When the production job opened up at Easy 101 here in Philadelphia, I got an interview and nailed the job. That was seven years ago.

JV: What shifts did you work during your on-air years?

Tom: I worked the evening shift at Magic, and I worked an Oldies show on Saturday and Sunday nights on KISS 100 in Philadelphia. I did mornings on WMGX in Portland—signed that station on, actually. I was the guy who threw the switch twenty-two years ago. That was a real unique experience. I never did middays or afternoons though.

At that point, the radio business was really starting to change as far as what you could do with the music. What you could do with music to me was the whole reason for getting into radio, and that was quickly being taken over by Program Directors. No longer could you walk in and program your own show, even according to someone else’s format. Now you had to play records from a sheet. At that time, the whole idea of getting into radio was to program music. It was a fun time.

JV: How did you end up making the transition into production?

Tom: I was asked to do it at Magic back in 1981. I thought it was great because I thought that was the door into management. My whole idea about getting into radio was, “Hey, look, this jocking is fun, but whoever heard of a fifty-year-old DJ?” I figured I had better do something to get off the air. So when Bob Craig at Magic offered me the Production Director job, I thought it was a great opportunity and I jumped on it.

JV: Tell us a little about WBEB and the station's success.

JV: Tell us a little about WBEB and the station's success.

Tom: Their success started long before I got there, of course, but it is really a unique radio station. We figured out that it’s the largest independent radio station in the country. Markets larger than Philadelphia include San Francisco, Chicago, Los Angeles and New York. Of the major radio stations in those markets, I think they’re all owned by groups. B101 is owned by two guys in Philadelphia, and the guy who runs it is Jerry Lee. Jerry has had the station for thirty-five years. I knew of Jerry Lee when I was working in Amsterdam, New York in 1976. Jerry was active in the NAB, active on a national level, and there isn’t an FCC commissioner that he doesn’t know. And he still has that sole property.

JV: What has the format history of the station been all these years?

Tom: It started in the early sixties as WDVR, which meant Delaware Valley Radio, and it was beautiful music—Bonneville. It was the first FM station to bill a million dollars. It was the first radio station, AM or FM, to have a TV commercial, and it’s been successful ever since that time.

JV: To what do you contribute this long term success to? They must put an emphasis on people.

Tom: Yes, it’s a people-oriented company, but as far as the success of the station on the dial, it takes outstanding programming. Jerry, even though he’s an owner, even though he came up through sales, is the single most savvy programming mind that I’m aware of, at least as far as an owner goes. Jerry has branded the radio station through help from Bill Moyes, the consultant, to simply be one of the dominant radio stations in Philadelphia. So I get an opportunity to see a lot of this stuff that maybe some other guys wouldn’t, and it’s a unique place to be.

JV: How do Jerry’s programming mind and the production department come together? What’s his philosophy there?

Tom: Jerry doesn’t get into nuts and bolts like I do, but the idea with production is basically make the production sound like the station. Give it entertainment value and high production values, but have it be consistent with an AC radio station. Now, over the years, that’s changed a lot. Twenty years ago when we were doing Magic, we’d be happy if we had a pretty decent music bed that matched a script we had written for a promo—you know, a single voice thing with absolutely no effects. That was our idea of a promo back then. I laugh to think of it because there’s not one guy whose work shows up on the RAP Cassette every month who couldn’t have destroyed us back then. The bar has raised so much since that time. So it’s my job to keep up with that and, hopefully, in some ways try to push it up a little bit.

JV: What kind of challenges are there to image a station that has such a large audience but in the typically tame AC environment? You probably can’t use all those bells and whistles that one might find with “in your face” type production. But at the same time, you’re trying to have entertainment and high production values, as you mentioned. What’s that dance like?

Tom: It’s a fun dance because nobody else does it. The way I like to see it is that we have brilliant, creative minds at my competition in Philadelphia. Christopher O’Brien at WYSP is an absolute monster and he’s not even old enough to drink. And these guys fully exploit the advantages of digital audio production in the late nineties, and they use all the plug ins. They use all the bells and whistles. They’ve got one station voice deeper than next. So where they zig, we zag.

And the way I like to express our ideas is with clean, well-executed production that’s consistent with the woman who’s listening to our radio station. But she is a woman, and we know that she doesn’t like to get banged over the head by aggressive sounds on the radio. We don’t play those records. We don’t play those commercials. And that’s not the way we do our imaging. We image the radio station in the way that’s consistent with that soccer mom who’s listening.

JV: Copy must play an especially important role.

Tom: And being an English major, I like to think in terms of using words to paint pictures rather than sounds. I like to use words with some help from the audio. I think words are really powerful if you choose the right ones and put them in the right order, and that’s what we rely on. There’s a lot of left brain, right brain stuff going on, and we support all of the ideas that we express through words with audio and pretty much whatever it takes to get the point across. But we stop short of sounding harsh and aggressive.

JV: How many people are handling the production there, imaging and commercials?

Tom: Chris Conley is the Program Director and handles the imaging. I’m taking on the higher end imaging and higher end commercial production. I also write spots from the ground up and create marketing plans for our retail customers who don’t have agencies to do that for them.

In the way of help, we’ve got Juan Varleta, who is a long-time Philadelphia on-air guy and a terrific asset to us. He does part-time on the air and helps out in production during the week. He handles most of the commercial production. Then we have a newcomer named Jason Collado. We’re training Jason as an assistant to Juan in commercial production, and Jason is really loving the idea of digital audio editing. You show him a loop and he’s excited. We’re creating a monster in Jason. He’s a work in progress.

JV: Who’s the voice for the station imaging?

Tom: The voice is John Pleisse. John is one of the sweetest guys you’d ever want to work with. He’s one of the chosen few right now, and with good reason. His voice is just like butter, and it’s just perfect for our demographic.

JV: So Chris pretty much lays out the copy for John, then you and Chris get the pieces and put them together?

Tom: Yes, and Chris has been doing increasingly more imaging lately. What we’ve done is—well, let me back up a step and go back to Jerry Lee. Jerry, in addition to being a visionary, believes that computers can do just about anything. There is not a gadget on the market that’s out there that Jerry hasn’t played with on a beta basis with somebody, or gotten it free, or taken it for a test drive and gotten back with the developer on how to make it better.

JV: A production guy couldn’t ask for a better owner than that.

Tom: You’re exactly right. And he’s done some great things with the help of our chief engineer Russ Mundschenk. Russ is the perfect engineer for our radio station in that he’s just flat out wide open, and he is probably the single highest authority on radio digital applications in the country. He’s spoken at the NAB several times on digital radio studio design, and he simply knows more than most people about the subject. So you’re working with two guys like that, and it just lays the whole thing wide open. We were one of the first ones to get the Orban DSE 7000 because we quickly saw the value of that. Now, I wasn’t there at the time, but my predecessor, John Beaty, had the pleasure of working with that. With some owners and General Managers at that time in the early nineties, there was no apparent advantage to working with gear like that. A lot of GMs at the time just thought, “Hey, we’ve got a 4-track. What’s the problem? What are you complaining about? We’ve got carts. You can put sound on carts.”

JV: But not Jerry Lee. He said let’s go for it.

Tom: Absolutely. He said, “If we can get a computer to do this, I like it.” I’m paraphrasing, of course. I wasn’t there, but that’s his whole attitude. So, in my time there, I’ve moved away from the Orban, which at the time was not networkable, and got together with the Sonic Foundry people because they were using WAV files, which could easily be networked. Now we have a site license for Sonic Foundry products in our radio station. Chris Conley does imaging for the station at his desktop. He doesn’t even tie up a studio.

JV: He gets the voice tracks from John into his desktop computer in his office and goes to work? Does he actually put sound effects and everything to it from his desk?

Tom: Oh, yeah. He’s doing most of the imaging right now and works from his desktop. He only gives me the stuff he really wants highly greased and highly polished.

JV: Stuff that requires more than a laptop, right?

Tom: More than a PD, okay? (laughs) Again, we don’t get too fancy, but for the basic meat and potatoes stuff, we’re using the desktops. It’s incredibly powerful. I can work on a project in my studio, and if I happen to be in the other studio for some reason, I don’t have to schlep back over to my studio to work on that project. I can just pull it up on the PC in the other room.

JV: Let’s talk about the production studios. I take it there are two?

Tom: Yes. We have an on-air studio and two production studios. Production One is mine. In there we have the 20-channel Zaxcom, which is digital. They had one of the first digital audio mixers to hit the market targeted for radio, and of course, we bought it because Russ was looking for a digital console that ran on AES/EBU, and this was the first one to satisfy that criterion. So we jumped on it, and that was about three years ago. We have them on-air and in both production studios.

JV: What are you using for the multi-track?

Tom: Well, I’m a fan of Sonic Foundry stuff, and I’ve been using Acid as a multi-track. However, it’s no secret that Sonic Foundry is a market leader in digital audio software. And ProTools has been embraced by many, many radio people with good reason. It’s just about the granddaddy of digital audio editors. Well, Sonic Foundry is introducing a product very soon to compete with ProTools and to wrest market share from them. I’ve been playing with a beta version of that product, and I’ve been loving it. It’s called Vegas. It’s a full-blown multi-track, and it’s just real sweet. I don’t want to get into too much detail because I don’t know all the stuff that it does yet, and I don’t want to say anything out of school. Let’s put it this way. I think anybody who does digital audio editing is going to love playing with it.

JV: And prior to this, you were using Acid as a multi-track device and apparently had no problems with that.

Tom: There is a learning curve, and weaning myself from the Orban was not exactly a fun process. The Orban is a terrific hardware tool that for me was just real fast and intuitive and very, very comfortable. But I felt that the precision I was looking for in editing, I couldn’t get with the Orban. And again, at that point, we had networking problems where the Orban was just not networkable at that time. Between our two production studios, that was a real issue for us. So we moved on to WAV files. And another advantage, too, is that we could have long program forms where before, the Orban limited us to sixteen track minutes or whatever amount of memory you had. And we needed a more economical way to handle long audio files. So, Sonic Foundry was out there, and it worked with WAV files very nicely. We do our public affairs show totally on WAV files. Our PA director edits the show at her desktop. It’s great.

JV: That’s like having more than just a couple of studios there.

Tom: Exactly right. Anybody who is involved in audio can edit at their desktop and leave the studios alone.

JV: And with everything networked, if you’re back in the studio and need some audio from one of the desktops, you just grab it from a shared file?

Tom: That’s all.

JV: That’s beautiful. So have both production rooms moved on to Vegas?

Tom: Vegas is only in my studio right now simply because of our agreement. Also, Sonic Foundry requested that we dedicate a machine simply to beta because they didn’t want to have to worry about other software being on the machine. So I’ve got a very modest P200 with 128 megs of RAM and simply nothing else. It’s loaded with Windows 98, Acid, Sound Forge, and now Vegas, and it’s working very nicely.

JV: Is there much outboard gear, or are plug-ins the effects of choice?

Tom: Well, plug-ins I use for sure. And I don’t mean to sound like a broken record, but we do use the Sonic Foundry things, XFX 1, 2 and 3. We use their Acoustic Mirror and their Noise Reduction plug-ins which are outstanding. We also have a Harmonizer that I never touch, and we have a MIDI setup which includes a Roland JV1080 synthesizer, a Roland GP8 guitar processor, a Roland MIDI keyboard, and a Kramer Pacer guitar.

JV: You’re a musician.

Tom: Well, yeah, I plead guilty.

JV: That explains the ability to take to Acid so well (pun intended).

Tom: You know, in New Jersey, Governor Tom Kean ten years or so ago had a slogan: “New Jersey and You, Perfect Together,” and we in this area have mocked that slogan forever. So, yeah, “Acid and Musicians, Perfect Together.”

JV: There are a lot of musicians in radio production rooms, and I can certainly see how Acid would really come in handy. Not only can you use it as you would a typical multi-track software program, but you have the ability to do lots of stuff with the music as well.

Tom: Yep. I make custom loops and stuff and drop them in when I can. It’s great. In fact, I was telling Debra Grobman over at Who Did That Music Library? about the Acid and MIDI stuff, and she just kind of rolled her eyes. Now Who Did That Music is probably the best stock music out there, I think. We use them, and I love them. But every once in a while, when you’re looking for something strange, it’s great to have the MIDI setup to fall back on. I’m not ever going to replace Who Did That Music, but I use the MIDI stuff as a supplement.

JV: Are you using any other libraries for music?

Tom: No.

JV: What about imaging libraries for AC? Are you using any or creating your own stuff?

Tom: Pretty much our own stuff. I get bored very quickly with explosions and zaps and lasers and stuff. And on the other end of the spectrum, when we talk with companies about softer stuff, they ask us what our format is and I tell them it’s AC. So they send me like John Denver sounding stuff. I don’t think they really get it, and I’m not going to argue with them. They make stuff, and they have a market for it. They sell it, and that’s good for them. But honestly, I’ll grab anything. I like to use different sounding music, and I think that raises the entertainment value. I’ll use world music. I’ll use new age. I’ll use Latin rhythms. I’ll use reggae, and not because we’re giving away a trip to Jamaica, but because it’s happy music, and it makes people feel good.

There’s so much great music in the world. That’s why I got into radio, and to only play a sliver of it doesn’t make a lot of sense to me. So, I’ll pull from anything and as long as it works in the spot or the promo. I’ll grab a bunch of CDs that we would never play and nick a little bit here or grab a little bit there. I find that’s a great way to make your promos sound contemporary and yet not have them be familiar. It’s also a time-honored tradition. I worked with Julian Breen when I was with Greater Media. Julian was the corporate PD, and Julian had the honor of working with Rick Sklar as Sklar’s Production Director at WABC. And the whole idea of those promos that Dan Ingram used to do was that there was no template. They were inventing rock and roll radio at that point. They were the leader in the world, so they had nobody to look to. They had no role models. And they found that using big band swing music under their promos gave them the drive, gave them the energy that they were looking for in their promos. So, as I said before, when other people zig, I like to zag. And if other guys are using a lot of drops and processing and a lot of thumpa thumpa, I’ll try to go the other way to sound different, to hopefully engage the listener in a different style.

JV: It’s obvious, just talking with you, that you have a very unique voice and one that probably does well in the VO market. Are you doing any voice work outside of the radio station?

Tom: Yeah. I like to do outside stuff because I like to make money, but also I like to throw myself into somebody else’s production as simply an element. In my studio, I’m the king. I go with my vision. I write my words. I produce my spots. But when I go outside, I squeeze myself into somebody else’s vision, and I like to use my voice in ways that help people out, that maybe somebody else might not be able to give them.

I’ve been told that I’ve got that warm fuzzy thing happening, and for a long time I battled it. For a long time I fought it and said, “Well, I can do more than warm and fuzzy.” Then one day I woke up and said, “Hey, wait a minute. What do you want to do? Do you want to be successful? How are people successful? By having a recognizable sound. What’s your recognizable sound, Tom? Warm and fuzzy.” So, I don’t fight it anymore. I go with it and try to develop it as much as I can rather than just sound like some friendly guy without any brain. I try to put some kind of spin on the words. To me, the way to voice a spot, the way to deliver a script, is the way the writer intended, the way the writer heard it in his head when he wrote the words. Either that or give him just a totally different read that puts a whole other harmonic on it.

JV: Any parting words of advice to those looking for an edge in their game?

Tom: Be fiercely original, and don’t be afraid to go for the sound you hear in your head rather than what you heard on somebody else’s radio station.

♦