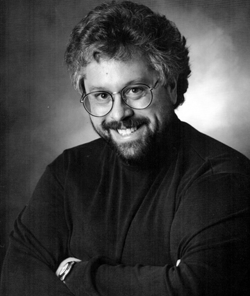

Howard Hoffman, Production Director, Talk Radio 790 – KABC, Los Angeles, California

For many, the name Howard Hoffman will ring bells from as far back as the early ’70s. Howard is one of the fortunate ones who was able to make a long and successful career of being a disk jockey, air personality, morning man, air talent, etc.. A little over three years ago, he did his last air shift and found a home in production at KABC, Los Angeles. Most recently, Howard was a guest speaker at the International Radio Creative and Voice-over Summit held last summer in Los Angeles. Production has always been in Howard’s blood as was evident when he was a 19 year old Production Director in Detroit, and his finely honed skills are sharper than ever today. Join us for a visit with Howard as he looks back on his extensive career, relates stories such as that of the notorious “Nine Tape,” and gives us a glimpse of imaging talk radio in the ’90s in the nation’s second largest market. Can a rock jock/production guy image talk radio? Can Paul Harvey rap to a Notorious B.I.G. beat? Yes and yes..

For many, the name Howard Hoffman will ring bells from as far back as the early ’70s. Howard is one of the fortunate ones who was able to make a long and successful career of being a disk jockey, air personality, morning man, air talent, etc.. A little over three years ago, he did his last air shift and found a home in production at KABC, Los Angeles. Most recently, Howard was a guest speaker at the International Radio Creative and Voice-over Summit held last summer in Los Angeles. Production has always been in Howard’s blood as was evident when he was a 19 year old Production Director in Detroit, and his finely honed skills are sharper than ever today. Join us for a visit with Howard as he looks back on his extensive career, relates stories such as that of the notorious “Nine Tape,” and gives us a glimpse of imaging talk radio in the ’90s in the nation’s second largest market. Can a rock jock/production guy image talk radio? Can Paul Harvey rap to a Notorious B.I.G. beat? Yes and yes..

RAP: Tell us about your start in this business.

Howard: Well, I was lucky enough to have a high school radio station where I went to school in Suffern, New York, and the faculty advisor for that station, Hank Gross, also held a weekend job at WTBQ, a radio station about fifty miles away in Warwick, New York. He got me my first job on the air, and the first thing I ever did on the air was a newscast. Somewhere in my collection I have a tape of that first newscast. It was just pathetic. I had a lisp, and everything that you could possibly do wrong, I was doing wrong. Somehow, I was able to parlay that into an eighty-nine dollar a week Program Director/afternoon drive job at that radio station. This was back in 1971.

RAP: Was this right out of high school?

Howard: I was still in high school. Some kids had a paper route. Some kids worked at the book store. I worked at a radio station fifty miles away. Now, I was the Program Director, but I didn’t know it at the time. The owner of the station would say, “Put together the records. Put this and that together every week, and it will be a lot of fun.” He was taking me for a ride, but that was the first radio station I ever worked for.

After that I worked closer to home in Spring Valley, New York. But the first job that really made a dent in my brain and my career was at WALL in Middletown, New York. That station was a high-energy, rocking, high profile, high personality Top 40 radio station. In the Orange County Pulse, it would consistently beat WABC in the ratings, which was a pretty good feat. This was in 1972 or 1973. It was an enormous amount of fun, and that’s where I first started doing stuff like putting phone callers on the air, clowning around with them, having a good time, hanging up on them and stuff like that. And they loved it. It was something that they had never heard anybody do before. It was at that station that I really made my first mark in the business, I would say.

We aimed high, and the station had a lot of production value. As a result, I really learned ninety percent of my production skills at that station. Of course, it was all analog, all reel-to-reel, all carts, but the station was just a production powerhouse.

RAP: Any mentors there at the time?

Howard: A fellow by the name of Jim Brownold, and he’s currently a voice actor in New York City. He was the Production Director of WALL at the time. He and I made some of the funniest stuff you’ll ever want to hear. We made some promos that were just dynamite. We did thematic promos in the style of game shows. We did some real Stan Freberg stuff. Our mutual heroes were Stan Freberg and Firesign Theater and the like. We always wanted to make our production values similar, at least on a par with those guys.

From there, at the tender age of nineteen, I became Production Director at WDRQ in Detroit. That was my first major market job. And to go from Middletown, New York to Detroit, Michigan was doubly frightening because it was the first time I was ever really far away from home. That was the summer of 1974 or the “Super Summer of ’74.” Sundown by Gordon Lightfoot and Midnight at the Oasis--I heard those songs until I was blue in the face. That’s my reference point for Detroit. After three months, a new Program Director came in, and I was gone. That was my first experience of being fired, and I really had a hard time handling that. It was like, “Hey, I’m supposed to be on my way up. I’m not supposed to be getting fired!” But I got over it and went back to Middletown, back to being Production Director at WALL, and I also did weekends.

RAP: I get the feeling you’re one of those guys with a long list of stations on your resume.

Howard: It’s just ridiculous. While I was working at WALL, I was also asked to do weekends at WPIX. Dr. Jerry was the guy who brought me in there and brought me to the attention of Neil McIntyre. Dr. Jerry, of course, is famous for the Crazy Eddie spots that used to be so prevalent in New York City. I think I met him at some audio show in New York, and he took a liking to me because I looked like Buana Johnny at the time. I didn’t know I looked like Buana Johnny, but Buana Johnny was one of his favorite jocks. So I sent a tape to him, and he played it for the Program Director, Neil McIntyre. They decided to put me on weekends at ‘PIX which grew into full-time work doing nights. That was during the disco era. So I made the big leap, and from that point forward, I did nothing but radio shows.

RAP: Hit some highlights. What markets did you visit along the road to L.A.?

Howard: Do you have a map of the United States? Let’s see, Pro-FM in Providence. Then ABC hired me at KAUM in Houston and then transferred me to WABC. I was at WABC from ’79 until ’82, which was probably the absolute highlight of my career. I hit every emotion during that time, as far as my personal life and as far as my professional life. I saw good things happen, and I saw bad things happen.

I was doing evenings, and just before my last year I got replaced by the New York Yankees. So they moved me to overnights. I told my mom, “Hey, it took nine guys to take my place!” Meanwhile, deep down I knew, “Last exit before toll, Howard. You’d better start finding something soon.” When that was over in ’82, I went to Phoenix. I did morning drive for the first time at KOPA. From KOPA I went to KMEL in San Francisco when they went Top 40 in ’84 and did afternoon drive there.

RAP: Were you doing production during this time?

Howard: I kept my production skills going through all that time. It amazes me that most of the people who are on the air today don’t know a thing about doing their own production. It was almost a requisite as I was coming up, as most of us were coming up through the seventies and eighties. You had to do production because you were always given a load of production to do after you got off the air. It just amazes me the number of people who are on the air who just don’t have production skills. They are missing so much by not being able to do that. It supplements your show. You understand the technical aspects of the business itself. You’re able to produce things for your own show, and you’re not so dependent on everyone else doing it for you. It just amazes me that nobody bothers to learn these things. It’s kind of sad, actually. I’m starting to sound like an old fart here, but people coming up right now just don’t know the joy of radio production. They just want to go right on the air, and they don’t want to do any of the other stuff. That’s really sad because a lot of people really are missing a lot by not doing radio production.

RAP: Why do you think it’s that way now? Why are these people not being given the production to do?

Howard: I don’t think they have the desire. If you start telling them about mixing and producing and editing, they just kind of turn their heads and start wandering off and wonder about what they’re going to do on their show. That’s not everybody. But a lot of people have avoided it over the last ten years or so. It’s like, “Well you’re the guy who is good at it, so you do it.” And I think, “Well, don’t you want to learn? It’s so cool!”

RAP: But back in those days, you learned because you had to. Why is talent not forced to do production today?

Howard: That is a good question. I wish I had an answer. I guess it’s because every radio station nowadays has somebody who can do all that stuff.

RAP: Which is a good thing, I suppose.

Howard: I guess. It makes our job a little more indispensable. It’s fine by me, but I still say a lot of people are missing out on a lot.

RAP: So where did we leave off? Were you in San Francisco?

Howard: In ’84 I went to KMEL in San Francisco and did afternoon drive. That was only going to be experimental, and as it turned out, it ended up being permanent and was just a wild success. Again, I brought everything that I was doing in the nighttime show into afternoon drive, mixing in a lot of stuff. I had a full team. I had a news person, a sports guy, and all these elements that you just don’t see anymore in afternoon drive radio. I was able to play off of these people and was able to have a lot of fun doing phone-oriented stuff and a lot of production intensive stuff.

I started getting into music mixing at that time because that was the first opportunity I had to work with an 8-track. I started making special mixes of these songs we were playing, and it just set us apart from everybody else. We had a drum machine and a synthesizer, and we were able to mix the “blaster mixes” of these songs with the regular vocal versions to make our own version. That was enormous fun.

Here’s something else I started doing at KMEL. All these groups that were really hot at the time, they’d come to the radio station for interviews. Then we’d get them in the production studio where we had the music bed of one of our jingles on hand, and we would have these artists sing our jingle. We ended up with a nice collection of maybe thirty of these after a while. They would just introduce themselves, and then you’d hear them singing the jingle. I produced these things, and it was a real kick because you’re essentially producing these giants of rock and roll singing the KMEL jingle. That was a lot of fun, and I got a lot of music mixing experience as a result.

After that, Gannett waved a lot of money in my face to move to Seattle to work for KHIT. Well, ‘HIT wasn’t the powerhouse that we hoped it would be, but we tried. That lasted nine months. Then for reasons unknown to me, I went back to Phoenix doing morning drive at KKFR. That was another very short run.

From there I began wondering what I wanted to do with my career because I was starting to face that old bugaboo of being forty years old and still doing Top-40 radio. So I decided to try Chicago. I stayed in Chicago about a year and worked at B96 doing the nighttime show, and I decided to try and do voice-over work. I did a couple of things while in Chicago, but I wasn’t there long enough. It usually takes at least two years before you can establish yourself as a voice-over person in any market, but I was able to get some inroads made.

Then Hot 97 in New York found out I was available, and they made me the producer for their morning show. They decided they wanted to match up Stephanie Miller with someone and do a male/female show. They were trying to find the right co-host for her, and the Program Director, Joel Salkowitz, finally said, “What about Howard? He’s done morning drive radio. He’s been doing Top-40 radio for a long time.” And so they put me together with Stephanie, on a trial basis, and the trial basis ended up lasting about three and a half years from 1989 until 1993.

Now, while I was at Hot 97, I had the pleasure of working with Rick Allen who was the Production Director there. And that was a very gratifying experience, really. That was my first experience with digital editing, and we just had an absolute ball putting stuff together. Rick is just incredible. He’s a good guy, a professional, and not only that, he’s so knowledgeable, it’s frightening. We had a very good time there.

The station started to go more in a hip hop direction, so Stephie and I were let go. She went her way, and I went my way. I moved back into my house in San Francisco for about a year and a half. I was renting it out, and my tenants were moving out just at the time I was getting fired from New York. So I moved back into my house in San Francisco, and for about a year and a half I genuinely contemplated what I really wanted to do in this business.

It really came to a head, I’d have to say, at the station that I worked at in San Francisco. You do reach a crossroads in your life, and this was it for me. They hired me on a part-time basis to do nights at KFRC where I did what ended up being my last on-air job. A lot of people remembered me from KMEL, and the radio station got a letter from a listener thanking them profusely for putting me on the air. The letter said things like, “He’s funny. He’s an exceptional talent. I’d never miss his show. I’m glad you put him on,” and so on and so forth. Well, the General Manager made an editorial about this letter. Now I know the letter was written about me because everybody at the radio station got a photocopy of this letter. It was such a well-written, nice, happy letter that everybody in the station got a copy of this, including me. Well, the General Manager made an editorial, and he read this letter on the air, but he credited the morning show instead of me. I found it to be extraordinarily curious.

I was doing nights. So imagine my surprise when I tune in one day and hear this editorial being played reading this letter verbatim except every place where it said Howard Hoffman, he’s saying the name of the morning show guy. You can imagine how I felt. And at that point, I just said to myself, “What am I doing?” I go on the air that night, and I look at the program log. They scheduled the editorial on my show, which is like the ultimate chutzpah. So I just go, “All right, Howard. You’re standing at this intersection. Which way are you going to go?” I think I took the low road.

Before I played the editorial, I went on the air and said, “I know the guy who wrote this letter is listening right now. If you could call me, I’d like to discuss this with you, this thing I’m about to play. So let me play it, and if you’re listening, the fellow who wrote this letter, please call in. I would like to ask you something.” I played the editorial, and sure enough, there he is calling in. I check out his name and address. Everything jibes up with the letter, so I go “Hold on.” The editorial ends, and I put the guy on the air live. I say hi to him, how you doing, and you’re name is such and such and, “...you’re the fellow who wrote that letter. Now what was strange about what you just heard?” And he says, “Well, I didn’t write that letter about your morning show.” And I said, “Who did you write it about?” And he says, “Well, I wrote it about you.” I go, “Aha, now that’s interesting. Our General Manager read it about the morning show. What do you think about our morning show?” And he goes, “They suck. I hate them.” And I said, “Well, why do you suppose the General Manager did that?” He goes, “Well, maybe because they do suck.” And I go, “Oh, okay. Well, I’m just curious, and I just wanted to clear that up. And, hey, I’m glad you listen. I’m especially glad you’re listening tonight because this is probably going to be your last opportunity to hear this show in its present form.” He and I both cracked up. We both knew that this was probably going to be my last show.

I called a meeting with the General Manager to clear the air on the thing. I walked into this meeting and, of course, the General Manager isn’t there, just the Program Director, handing me a check and a pink slip.

So I decided to pursue something else, and this opportunity to be a Production Director at KABC presented itself. I thought, “Great. I don’t have to be on the air. I don’t have to listen to any more editorials. I don’t have to take any more abuse.” And this is essentially the moment I’ve been waiting for because now I can safely say that I’m not forty years old and a Top-40 disk jockey, not that there’s anything evil about that, but you just can’t keep doing that for the rest of your life. I just didn’t want to end up being one of those rock and roll dinosaurs that I absolutely feared being.

The fellow who hired me, Al Brady Law, was also my Program Director at WABC. He hired me, but he did it with some fear and trepidation because he felt for sure I was going to do this for three months and then go somewhere for an on-air shift. Boy, was he wrong. I started at KABC in June of 1994, and in spite of what many people thought, I ended up staying there. I’m still there, and I’m absolutely loving it.

RAP: That’s quite a history, and it sounds like you had an amazing run on the air.

Howard: Oh man, I’m telling you, it was a great run. It was a wonderful run being on the air, but I’m so happy doing what I’m doing now. I never thought I could find happiness in this business again, and I have.

RAP: That was a great look at some days gone by. Let’s talk about today. What are your responsibilities at the station?

RAP: That was a great look at some days gone by. Let’s talk about today. What are your responsibilities at the station?

Howard: The promos, and to a pretty large extent, the commercials. I’m probably one of the few Production Directors in a major market who still actually deals with commercials. Most Production Directors deal only with promos, and they have an assistant who takes care of the spots. My assistant, Jeff Shade, formerly the Production Director at WFAN, and I both take a very active roll in the commercials. The reason for that is because I do commercial voice-over work on the side. Doing the commercials for the radio station kind of allows me to keep myself in practice.

Jeff is terrific. I don’t know if you’ve ever heard any of his stuff when he was on WFAN. As a Production Director of an Emmis station, you have to be pretty top-notch, and Jeff is.

RAP: Are there other stations at the facility?

Howard: Well, it was KMPC. Then it was KTZN, The Zone. I had the dubious distinction of being the person who came up with their slogan, “Talk radio is not just a guy thing anymore.” After about six months, they found out it probably was. The station didn’t do too well. It never got higher than a point five, and Disney came in and made it Radio Disney about two months ago. Radio Disney sounds pretty good. It’s probably one of the better computerized radio services I’ve ever heard. It’s almost seamless the way they present it with the local cutaways and everything.

So, there are two stations here, but we don’t deal very much with Radio Disney anymore simply because they do their own promos. If we do anything with it, it’s mostly commercials.

RAP: Describe a typical day for you?

Howard: I start at seven in the morning. I remain on standby in case Minyard and Tilden, the morning show on KABC, need any comedy elements or production elements. So far I’ve done close to a hundred bits for them, and that responsibility started only in May or June. But it’s fun, and they’re an appreciative audience. And it helps the station sound topical and helps the morning show sound a little more in touch and a little more hip.

I bring all the Top-40 sensibilities that I’ve had throughout my career and transfer them into this talk radio station which a lot of people had written off as being a dinosaur. Hopefully, with what I’ve been doing with the promos and the little elements in the morning show, we’ve become, at least sound-wise, a very contemporary radio station.

Anyway, I get in there at seven o’clock and put in about three or four hours of work. Then I’ll hit the streets for about an hour doing auditions or sessions for commercials and cartoons. Then I get back around noon and spend the rest of the day putting together the promos and elements for the next day. Then at three o’clock, Jeff will take over and finish up what has to be finished or take care of whatever comes in at the last minute.

RAP: How many spots would you say you guys are producing each day?

Howard: In the course of the day, we probably do anywhere between eight and twelve. Granted, some of it is just straight voice-over work, but a lot of it is specialty voice work. A lot of it is dialogue work, and a lot of it is effects work.

RAP: What equipment are you doing this work on?

Howard: We have both an ADX and the DSE-7000, and they’re constantly in use when we’re there.

RAP: Are there two studios?

Howard: Technically, yeah, but we both work out of the same studio.

RAP: Are the ADX and the DSE-7000 in the same studio?

Howard: At one time they were. The DSE was moved into Studio K which used to be The Zone air studio, and now they’re using it to edit things on the Stephanie Miller Show which is on every night between seven and nine. It’s ironic that Stephanie and I are working at the same station again.

RAP: What do you think of those two machines, the ADX and the DSE-7000?

Howard: The DSE is always going to be the hands-down favorite as far as just being a virtual 8-track tape deck. I like the fact that it’s so fast. You can whip out something on that thing in no time. On the other hand, even though the ADX is a little more cumbersome to use, it’s much more flexible. And the DSE only has one undo step. A Production Director’s best friend is that undo button, and whoever invented the undo button is my friend for life. As far as doing intricate productions, as far as production with a lot of little elements that have to be shifted around, that have to be grouped together and moved from one place to another, the ADX is just about heaven-sent. It took me a while to master, and it was very intimidating when I first saw it. As a matter of fact, KFRC had one, and I tried using it and just got scared to death. But now that I was forced into the situation of having to learn it, I love it. You can’t take it out of my hands now.

RAP: What are the pros and cons of imaging a news/talk station versus a contemporary music station?

Howard: A contemporary music station is less of a challenge, of course. You know what your format is. You know what kind of music you should have in the promos. You should know what kind of underlying theme you should have in everything that you do. With news/talk, it’s a little bit trickier because you have to know who the target audience is. You’ve got to figure out what kind of music they’ll get off on because the people listening to talk radio aren’t listening to music stations for whatever reason. You have to pick out stuff that you think they’ll enjoy without really offending their sensibilities. That’s not to say that everybody who listens to talk radio is a senior citizen, but people who are listening to talk radio just aren’t listening to music. So you really can’t be too intrusive, but at the same time, you really want to get their attention.

So you’re trying to strike a balance there, and it’s that balance which is a real challenge. I really like it. And as time has gone on, we’ve gone from being kind of mainstream Top 40-ish to being a lot more edgy in our presentation on the air. We’ve really gotten to a point where we almost sound, at some points, downright alternative. We’ve started to use a lot of different influences in what we do. How can I not invoke the name of John Frost? He has essentially set the tone for production in Los Angeles. I’ll hear things that he does...we’ll all hear things from each other and adapt them to our own situations.

But we’re trying to carve out our own image. KFI, our main competition, has been using the same imaging for the last ten years, which much to their credit is working for them. They’ve been consistent. People know what they’re getting when they listen to that radio station. KABC is still trying to find that one image, that one magic thing that we can actually hang our hat on and say, “This is what we are. This is what we do.” We’re zeroing in on that, and in the course of that, I’m doing a lot of really fun experimenting. It’s an enormous amount of fun throwing stuff against the wall, seeing what sticks, and I think our sticking ratio has been very good. Much credit to KABC because a lot of the ideas I come up with, they take my word on. Then, when I execute them, they say, “great” and put them on the air. They basically give me free rein.

RAP: What’s the lineup on the air? Are there some syndicated shows originating from the station?

Howard: Well, the only well-known syndicated show we have right now is Art Bell. That’s on between midnight and four. We do have a show between nine and noon, Ron Owens, who simulcasts his show on our station and on KGO. But aside from that, the rest is local programming.

RAP: Is the lineup the usual sports shows and psychologists?

Howard: Not any more. We got rid of the Dodgers. As soon as the season ended, all the sports programming went bye bye. Now everything is very issue oriented. There is some lifestyle material, but it’s mostly issues. While the other talk stations in town are essentially all attitude, we’re the station you can come to when you want to talk about issues and the news.

RAP: You did a workshop at the Dan O’Day Creative and Voiceover Summit last summer where you talked about this type of imaging that you’re doing. Tell us a little about your workshop.

Howard: Dan made no bones about it; I was there to show that you can do the same kind of imaging you do on rock and roll radio stations on a talk radio station. I had examples of things and we played tapes. Perhaps one of the more notorious things I did--you should pardon the pun--is this piece I did using a Notorious B.I.G. track. Boy, I wish I could remember the name of it. It was the first track off the last Notorious B.I.G. album. It was the one that sampled Rise by Herb Alpert. I took that and made a Paul Harvey rap out of it.

The idea started as I was walking past Studio C, which is our other production studio where they do a lot of the dubbing and pre-record a lot of show segments. Some guys were in there goofing around, and they had Paul Harvey in cue. They were recording The Rest of the Story for playback later on, and another guy in there was listening to the Notorious B.I.G. track. We were all listening to this and going, “My God. It almost matches up!” You’d swear Paul Harvey is listening to this Notorious B.I.G. track on headphones as he’s doing The Rest of the Story. I said, “Okay, give me everything.” I accept the challenge. I go into the digital studio and make this Paul Harvey rap. It was an entire The Rest of the Story done to this beat. The original ended up being about three and a half minutes long, and we knocked it down to a thirty-second promo and started running it like crazy on the air. It’s probably the high point and the low point of my tenure here. We did it, and people just absolutely loved it. Then we pulled it because the publishing company for Notorious B.I.G. called and hit us with a cease and desist order. That was fine because the promo ran its course. We had already played it to death by that time, so we got the mileage out of it that we wanted. I don’t know of any other station, ABC or otherwise, that set Paul Harvey to a rap beat. We did it, and these are the kind of things that they not only let us do, but encourage us to do.

Getting back to the workshop, I think people were really genuinely surprised that you can do this kind of stuff on a talk station. I guess everybody thinks that news/talk stations are supposed to have this responsibility toward the community, and you’re supposed to have the voice of authority and pooh pooh all that childish stuff. Not all of us have grown up. In fact, I dare say that most of us haven’t grown up. If you listen to the phone calls on talk radio, you’d see that almost nobody has grown up. So it’s not like we’re pandering or anything like that. I just think that not everybody has lost their sense of fun, and in talk radio, that’s especially true right now. A lot of people are going for a more human approach, a more, “we’re not taking ourselves so seriously anymore” approach. I think that’s basically what we’re trying to convey at KABC because KABC was always like the old gentlemen’s radio station for the longest time. We’ve been trying to break that mold, and hopefully people will know that’s exactly what we are trying to get away from.

The promos we run for the individual shows have a real high-paced, attention getting, filtered, sampled, layered sound. We do promos on an every other day basis, and each one of these promos is so highly produced that it’s amazing we can turn them out so quickly. But we’ve gotten to the point that we know how to do this so well that we can churn out one of these promos in anywhere from twenty minutes to an hour. We try to keep them topical and current. And thank goodness, a lot of the news stories that come out have a shelf life of more than one day, so we are able to let them run for two days before we update them again.

RAP: That sounds like an incredible turnover rate for promos.

Howard: It really is. We could farm out the promos to each individual producer of each individual show, but in order to get a proper campaign going, you really have to be consistent. I think that’s what KABC has really had a problem with over the previous God knows how many years. They’ve been trying so many things and so many approaches on the air that they really need something that will bind that radio station together. Hopefully, that’s what we’re doing with our presentation.

RAP: I would imagine you probably get a lot of your ideas just from the news of the day.

Howard: Oh, absolutely, the people talking about it, the host talking about it. I mean, you can put together a real good high-energy presentation out of that. We essentially have a promo bed with a beginning and an end, and we just have to come up with the middle. The middle is always the callers and the host discussing, laughing, yelling, joking, screaming about the hot topic of the day.

RAP: It seems the news/talk format might be the perfect format for the “veteran” CHR producer looking for a place to land, that person who can’t quite feel at home with an alternative rock format or something like that.

Howard: Well, it works out nicely for me. I can’t kid myself. I can’t say, “Hey, I can go on the air and do that.” I’ve done that. I hate to use an overworked phrase like, “been there, done that,” but where I’ve been and what I’ve done, I’m very proud of. And at this point, I see no reason to try and top that. I’m glad there are other people who can step into that place and carry on the mantle of good personality radio. They’re out there, and they’re doing it.

As for me, I want to embark on a career doing voice-over work, most notably cartoon voice-over work, something I’ve been wanting to do since I was a kid. I owe that to my father because he was the first person who ever taught me that adults can sit down and watch cartoons and enjoy them. He used to sit down and watch them and enjoy them with me and just laugh his head off. And I’d think, “There’s something pretty noble about this. I’m not quite sure what it is, but there’s something really noble about this.” As time has gone on, I realize it’s not really noble, it’s just a lot of fun to do.

When you work on a cartoon, you’re dealing in a real group performance. It’s an enormous amount of fun, and the people at KABC allow me to go out and pursue that while I’m doing the work here. The Program Director, Dave Cook, said to me once, “If you’re not good enough to go out and do outside work, why would you be good enough to be the Production Director of this radio station?” That was like the greatest thing I heard. So KABC allows me to go out and pursue this because they know it benefits them. And doing what I do on KABC allows me to be a lot more sharp when it comes to doing the voice-over work for the outside stuff. It works to everybody’s benefit, and it’s just great that they recognize that.

RAP: Are you using the Internet in any way?

Howard: Yes. I have a Web site. Everybody’s got a Web site. For about a year and a half now I’ve been maintaining my own Web site, and I’m kind of proud of the fact that I maintain the site myself. You can reach it at www.toonvoices.com. All my commercial demos, my promo demos, and my cartoon demos are all on there in RealAudio. I put that on my business card so that if people don’t have time for a demo, they can just click on the Web site and hear it. I’ve had a total of over three thousand hits since April on the site. A lot of those are people who are curious about voice-over work. People write to me asking me about voice-over work, and I have a pre-written thing about doing outside voice work that I’m more than happy to send out to people if they’ll just ask for it. If they just send me an e-mail, I’ll send them a copy of it. The e-mail address is hhoffman@ toonvoices.com.

RAP: Are you doing anything else to market your voice-over business other than the Web site?

Howard: I have an agent who does a lot of the footwork for me, and they’ve been very good to me. I’ve been with them for close to three years now. The work is coming in, especially the commercial work. The commercial work all summer has just been outstanding.

RAP: Are you doing any cartoon voice work?

Howard: I soloed for a cartoon that ended up being Hanna Barbera’s first Academy Award nomination. It was called Chicken from Outer Space. I played like six or seven roles on this cartoon, most of which was barking, grunting, screaming, yelling, cackling, and laughing. The only line of dialogue comes at the end of the cartoon where the dog says, “This shouldn’t happen to a dog” in a Jackie Mason voice. But the rest of it was just all these animal sound effects, old lady screaming, old man laughing, chicken cackling, dog barking, dog squealing. The really cool thing was that in the closing credits, I got credit for all of the voices. It was really cool to see my name go by in the credits. And when we found out that it got an Academy Award nomination, we were absolutely thrilled because it was Hanna Barbera’s first. It was for a cartoon series they have on the Cartoon Network, and the director/producer, John Dilworth, showed it at this little film festival which made it eligible for an Academy Award nomination. Just for the heck of it, he sent it to the Academy, and it got nominated. It was one of the five finalists. Hanna Barbera called him that morning and said, “How did that happen?” And he thought, “Oh my God, I’m in big trouble. I showed it at a film festival, and now they hate my guts.” And they go, “This is great.” They took it the right way, and they promoted it as being the first Academy Award nominated Cartoon Network cartoon. Since Hanna Barbera had done nothing but TV work all these years, this was the first time they had received an Academy Award nomination. So it was a real big thrill for everyone.

We didn’t win because Nick Park, the guy who did Wallace and Grommit, did a feature that year. So as soon as we saw that on the list, we said, “Oh, no. Why this year?” And, of course, he won. But at least we lost to a more than worthy competitor.

That was the only one cartoon I was really featured in. I’ve done background stuff, two or three lines here or there, and right now they have me auditioning for a lot of new series that are coming up. So I’m keeping my fingers crossed. There’s an enormous amount of talent out here.

RAP: You probably have a ton of interesting stories from your lengthy career. How about a story from the archives?

Howard: Well, while I was in Middletown, New York, we came up with something which is still notorious to this day, and that would be a little thing called The Nine Tape. It was done around Christmas-time, 1974. A bunch of us got together, two of us who worked at the station, and two of us who didn’t. It was me, Randy West, Pete Salant, and Amos B. Moses. The four of us got together in the production studio at WALL. We had been heavily under the influence of various ingestibles, and we put together this imaginary radio format which was based on a radio station in Hackensack, New Jersey, WWDJ, which, when it first went on the air, called itself 97 WWDJ. Then they shortened it to 97-DJ. And for whatever reason, for about a week they started calling it 9-J. Randy and I were driving around listening to this, and we look at each other and go, “What’s next? Are they just going to open the microphone and yell Nine?”

Well, when you have a conversation like that in the car, you say, “We gotta go to a studio. We’ve got to get to a studio and do this.” So we wrote this thing, made up this consulting firm, and decided to show the evolution of a radio station. I don’t know why we chose Pound Ridge, New York. It was an exit off the Sawmill Freeway in Westchester County, New York. You get off it and drive, and you’re back on the Sawmill Freeway. So we figured that Pound Ridge didn’t really exist. And we tried to think of the most difficult set of call letters you could think of, WVWA. If we had been less under the influence, we probably would have come up with WUWA, but what’s done is done.

We did mostly the narrative, the vocal part that first night. Later on we added the music, the songs. Then we made the jingles. Before we could finish it, the aforementioned Jim Brownold, who was at the time the Production Director of WPLJ in New York, got hold of the tape and made a copy of it. Of course, at WPLJ, you can’t do anything without an engineer. Well, the engineer made a copy of it, and he made dozens of copies for his friends. Before we knew it, this tape had gone from coast to coast in a matter of two and a half to three weeks. I mean, everybody was getting their hands on this tape. To this day, I still get phone calls and e-mails from people saying, “I have an eightieth generation copy of this thing. Can you send me a new copy?” I seriously cannot keep up with the demand. Twenty-five years later, I’m still getting requests for a fresher copy of this thing.

RAP: Well, I can’t think of a better way to help you out than by putting The Nine Tape on the Radio And Production Cassette!

Howard: Sure thing. No problem. It’s about time, after twenty-five years, that everybody deserves a fresher copy of this. I think you’ll like it. It’s been my calling card for twenty-five years. And for everybody who worked on it, it’s been their calling card for twenty-five years, too. “Are you the guy who yelled nine?” “Yes.” “Are you the guy who narrated it?” “No, that’s Pete.” Everybody has been able to parlay it into a verbal calling card. That’s probably the most notorious thing I’ve ever done. And I’m very proud of it, too, because it really sent out a message to all the tightly formatted radio stations of the day saying, “You can’t get away with this without us lampooning it.”

RAP: To programmers of talk radio stations, what advice would you give about imaging their station?

Howard: It’s such an easy word to say, and it’s such a hard word to define. Actually, it’s a hard word to find, and that is creativity. Whatever your competition isn’t doing or whatever holes your competition isn’t filling, as far as the creative process goes, you have to jump in there and say, “Okay, we can own this franchise.” You’ve got to find something, and you’ve got to own it, something that your competition either isn’t capable of doing or doesn’t want to do for whatever reason. Just do whatever you can to make your station stand out.

RAP: Any tips for your fellow Production Directors?

Howard: I try to make the production department of the radio station the lowest maintenance department there. You’ve got sales. You’ve got marketing. You’ve got programming. You’ve got continuity. You’ve got traffic. You’ve got all these people, and everybody wants attention. I try to do everything I can to make everybody else’s job easier so that when management takes inventory of all the different departments, they can point to the production department and say, “You know, they’re not giving us any problems.” I like hearing that because it means that I’m doing my job and taking a lot of the burden off of their shoulders. It’s a good feeling.

If you’re a Production Director, try to make your department the lowest maintenance department you can. That means being cooperative. That means pitching in and doing what you can to make everybody else’s job easier. And if you’re stuck in the bugaboo of doing commercials, see it as an opportunity. Don’t see it as a chore. See it as an opportunity to try doing character voices, to try doing different production techniques. Just see it as more practice to go on to bigger and better things. Don’t see anything as insignificant because you never know who is listening, and you never know who might want to use that special way you did that spot in something bigger. You never know.