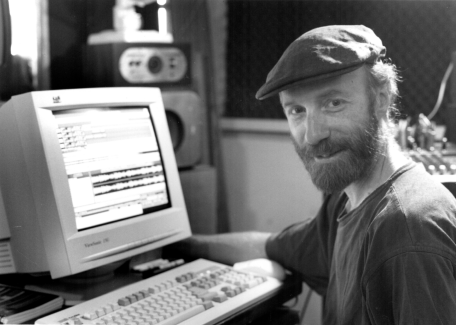

Peter Cutler, The Demodoctor, Los Angeles, California

Some of you may remember an amazing interview several years ago with Marice Tobias, the Voice-over Coach of the Pros [December 1991 RAP]. While Marice gets the most out of a talent's voice, Peter Cutler is the man who puts the demos together. Recently, his work with Marice has enabled Peter to leave a studio gig of many years to start a business of his own as The Demodoctor, and today, top voice-over talent are lined up to have "the doctor" write a prescription for the perfect demo. If it's time to update your voice-over demo, read this month's interview first. You'll find a wealth of information about demos, as well as some production tips you can use in your studio today. Be sure to check out the Demodoctor's demo on The Cassette! And if your demo needs a doctor, give Peter a call. His numbers are at the end of the interview.

RAP: What's your background in radio?

Peter: I started when I was fourteen at a noncommercial station here in Los Angeles that's still in existence, and that's KPFK. KPFK is one of only five stations around the country that's associated with Pacifica. Pacifica is a foundation that was founded in 1949 by a guy named Lewis Hill. It started when FM was brand new and grew and grew. It's just a very unusual kind of a station because they get almost all their money from listeners. NPR stations get grants and corporate underwritings and things like that, but KPFK gets almost nothing in terms of that. We get on and do fund drives two to three times a year. With this kind of station, in 1971 or 1972 when I started, I could just go down to the FCC, get my license, and be on the air the next week running the board and even announcing and producing programs and whatever they needed me to do. So I started with that.

About a year later, I met a couple of people named Howard and Roz Larman, and they do this radio show called Folkscene. They are icons in the folk acoustic music world. They started their show in 1970 and they're still on the air. I started with them in 1973, at first just running the board for them, playing records and whatnot. But after a while, I graduated to doing all the live mixing on the show. We do live music almost every week. I've been doing that for many, many years now, and I guess that's where you could say I sort of developed my ear. And I love music. I had been a guitar player, singer and song writer, too, so it all sort of connected together.

RAP: Are you still doing this show?

Peter: Yeah, I'm still doing the show every Sunday night from eight to ten. It's twenty-three years of my life at the same station doing the same show. We're live on Sundays, then they do a rerun on Tuesdays.

RAP: Is this on a network of any kind?

Peter: No, it's only on KPFK here locally. But what happens is a lot of listeners make tapes at home, and we know that these tapes fly all over the country because we get letters and faxes and e-mail from people who are way out of our signal range who have heard the show.

There's been talk about putting the show on a network. For a while they were on KCRW here, which is a flagship NPR station. My feeling is that if they were on KCRW now, given that KCRW is one of the flagship NPR stations, there would be a very good chance that they would be on satellite. But Pacifica doesn't really work that way. It's not a true network in the normal sense of the word. It's the kind of network where if there's big news somewhere, it will be on the Pacifica bird and the other stations can pick it up, but otherwise, all the individual stations do their own programming.

RAP: Do you do anything else for the station?

Peter: Yes, I do. Occasionally, they'll call me up with a live event they want to do usually involving live music, and I volunteer my time. I'm not paid for any of this. This is just something I love to do. I was on the payroll with them once many years ago, in 1979, I think. I was on staff for maybe six to eight months and had a board shift and a production shift. That went fine for a while, but they ran out of money to pay me during that time, so I just went on from there as a volunteer.

RAP: What did you do to pay the bills?

Peter: When they laid me off in '79 and I needed a real job, I found a studio. It no longer exists under the name it had in those days. At that time, it was called New Jack, and it was owned by Alan Barzman who is pretty well known in the comedic, commercial voice-over field for writing and producing spots. I'd heard his voice for years and years as a kid. When I finally met my boss, I couldn't believe I was meeting this guy because I'd heard his voice on lots of commercials. At that time, I thought I wanted to just work in a recording studio somewhere and record rock and roll music, and I really didn't know the kind of studio I was employed at for a while. I was so green that I saw multitrack tape machines and boards and just loved it. But it really took me a while to figure out that this wasn't exactly the music industry. At first they had me making tape copies of a musical group, but after a few weeks I realized what was going on. Shortly after I started there, somebody quit, and I was thrust in the position of being an engineer, creating commercials, and I liked it.

So I stayed there for a couple of years and really learned a lot. I worked with some amazing people. It was during that time that I met and worked with the legendary Stan Freberg and a lot of voices from the great days of radio who were still alive at that time, guys like Frank Nelson and Vic Perrin and people at that level. Vic Perrin was the voice of The Outer Limits. So, to me, he was a real icon. Guys like that had been in live radio in the late forties into the fifties. Anyway, Barzman would write these really funny spots, and then he would hire these people who were legends in the industry.

RAP: Where did you go next?

Peter: In 1981, a friend of mine had been working at a studio down the street which also no longer exists today. It was called Sun West, and they did mostly television work. They did scoring for shows and post-production sweetening of shows. At the time, they were one of THE places to go for that. The money was good, and I thought this was an upward move, so I went over there. Unfortunately, even though I did learn a lot while I was there and I don't regret it now, at the time the studio was on its way down. I ended up not being real happy after a while. About another year or so later, I left there and actually went to work for a guy I had worked with at the first place. When I worked at New Jack, my boss was a guy named Fred Jones, and we got along pretty well. He started his own studio right about that time in 1982, and he said, "Do you want to come work for me?" Since the other place was going down the tubes, and because I wasn't really thrilled with television work anyway, I said, "Sure, if I can do comedic radio, if I can do creative radio type stuff again." So he hired me. That was Fred Jones Recording Services as it was known from then until about 1991, and I worked there basically from late 1982 until 1991. That's the longest time I've been anywhere.

From 1991 on I've been on my own, doing a lot of work with Marice Tobias [RAP Interview, December 1991]. More recently, I've started The Demodoctor, which is just kind of an outgrowth of having worked with Marice the last few years.

RAP: How did you hook up with Marice?

Peter: She had been doing demos with another guy in town for a long time. He got real busy, maybe burned out. I'm not really sure what happened, but he couldn't do them any more. She was producing a demo with somebody and had used another engineer somewhere. Her client was not pleased with it and neither was she. Somehow she heard of me and came to me kind of as an experiment. We got along really well right from the beginning, and the client was real pleased. So she said, "Gee, do you want to do a few more of these?" and I said "Yeah." That was in mid-1990. So I was doing that and my regular job for a while. There was probably a six or eight month period where I did both. I just loved the work right away because I had the freedom to do the kind of production I'd always wanted to do without the time constraints of regular sessions and all the other pressures that go along with that. It was a dream come true in a way.

After that six or eight month period when I was doing both jobs, I made a very conscious decision that I was going to take a pay cut to do this and build it up because I'd pretty much had it with being a staff engineer. I learned loads and loads of stuff and will always appreciate everything I learned, but I think eventually you get to a certain point with a gig like that where it just takes its toll on you. I think it's a young person's vocation. That's my personal opinion. As I got into my thirties, I think I tired of it and wanted to find an escape from the daily grind of it. I'm really pleased with the growth and the fact that I'm working with some of the top people in the industry now.

RAP: How did The Demodoctor come about?

Peter: It just came to me one evening about two years ago. Marice and I do demos totally from scratch, and it's a big job as you might imagine. But there's also that group of people who are well established, who have a lot of material already on tape. They say, "I need to make a new demo. Here's my stuff. Make something creative." I would always have people calling me, even when I was a staff engineer, saying, "Make me a demo from this." So it occurred to me one night as I was doing that. I felt kind of like a surgeon sitting there. It was still in the analog days, and I was still cutting tape with a razor blade. I felt like a surgeon cutting away at their stuff, and this image of The Demodoctor came to me. I found out a little later that there is somebody else with that name. However, that person does pop and rock music demos, and our clientele seem to be very, very different. If anyone ever hears of another Demodoctor, I guess it's this other fellow.

Anyway, the difference between what I do with Marice and The Demodoctor is that with Marice we do demos from the ground up. With The Demodoctor, clients come to me with a pile of tapes and say, "I need to create something." My strength is really editing production, creative work like that, and Marice's strength is obviously directing and working with talent. I've learned a great deal about working with talent from her, but I think the reason we make such a great partnership is that we're so strong in our individual areas.

RAP: Who are some of the major talents you've done demos for?

Peter: Here in L.A., we're working with Neil Ross. I'm also working with Gregg Berger. These people are heavyweights in the voice-over industry. We're also working with Christina Belford. She is the voice of the Southern California and Northern California Honda Dealers' Association. Those spots are running all over the place over here. We work with clients all over the country. In your area, there in Dallas, I did demos for Bob Magruder and Jerry Houston.

RAP: What are some of the things you've learned from Marice about working with talent?

Peter: I actually started learning things about working with voice talent when I worked with Alan Barzman because he was a fine director, too. After I left there and was working at the other studio, I was more of a just an engineer and had to pull back on my directing and just kind of let the clients do that. I saw that there were a few people who were agency producers, who really did know a lot and were wonderfully creative. But there also was a certain group of them that, shall we say, had a few things they could learn. I would see the talent, the actors that I knew so well, receiving direction from these people and kind of looking at me wincing. "Does this person know what they want? Why do they keep directing me this way?" It occurred to me that directing is, first of all, a very daunting task, and a lot of these agency people, I think, were intimidated by the actors and didn't know what to say to them. They kind of kept telling them to do it again and try it this way and go up on this word, that sort of thing, a kind of mechanical direction. The actors really got lost. So many takes later, we finally got it just by accident.

I learned that you have to learn how to relate to the actor in terms that they can understand and not over direct them. Just give them an attitude, give them a point of view, a place to come from, who they are in the spot, and let them do what they do. If you've hired good actors, they can handle it. A lot of times, these directors would just direct it into the ground, and the actor would just get confused. I guess you could boil that down and say less is more in terms of direction.

RAP: Do you do demo tapes for inexperienced voice-over talents as well?

Peter: Well, I have, but I tend to shy away from it these days, partly because a lot of those people can't really afford me at this point. I put a lot of time and effort into these demos, and that costs money. I mean, it's a lot of my time. Plus, we have a pretty good clientele of fairly experienced people now. So I tend to tell the inexperienced people, "Get yourself into a workshop and work on your career for a while."

RAP: How much do you charge for a demo?

Peter: It would depend on how we're going about doing it. Marice and I charge $3,000 to do a demo from scratch. That covers everything including the copy search. She coaches them and gets them ready for the session. Then we do a recording session of three hours or so. Then we do the production and create a full-length version as well as a minute version for the house CD. And we allow a little bit of revision time in there for any changes that might need to be made.

Then I also work on an individual basis with performers and work on an hourly rate most of the time. Right now I'm charging $65 an hour to have people come in and edit or mix with me, or just hand me the stuff and leave me alone. I've been known to make package deals. We work it out on a kind of case by case basis. For example, I'm working with some fairly well-known talent locally where we're creating CDs for them instead of a cassette. Cassettes are basically going away in terms of demos. They are going to create CDs of their own in addition to being on an agency CD. On that disk might be four, five, ten, whatever number of categories they want to break their career out into. So, depending on how much work it's going to be and how many sections, etc., I might just say to them that it will cost X amount for the whole deal. That way you'll know what you're getting into from the beginning.

RAP: You said a demo for the "house CD" should be a minute long. How long should the full-length demo be?

Peter: They're getting shorter all the time. When I got into the industry, demos commonly were three minutes and even more. Now they're about two minutes. When Marice and I started out together five or six years ago, our demos were about two and a half, and that felt about right at the time. But shortly after that, within the last three years, we were getting comments that two and a half minutes seems a little long, so we just started cutting back. Now the de facto time seems to be about two minutes.

RAP: Is it better to present demos on CDs these days?

Peter: I think so. First of all, it should have happened years ago. The reason it didn't, obviously, was manufacturing cost. The manufacturing costs now are down at the level of cassettes. The obvious improvement in sound is there, but so is the flexibility. With cassettes being a linear format, you play them, then you have to rewind them. And if you want to look for a particular section, you have to wind around until you find it. On a CD, you can go immediately to a cut called "Character" or "Dialogue" and hear what you want to hear. It can be indexed any way you want. Also, the problem with cassettes has always been that they never sound the same from machine to machine. You make a bunch of copies for somebody that sound great on your deck. Then they'd send it off to somebody else, and it would sound real muddy because the Dolby didn't work right or whatever.

RAP: What are the main objectives of a voice-over demo? Obviously, one objective is to get business, but when you make a demo, what do you want it to do?

Peter: That's a really good question, and I've only in the last few years of working with Marice begun to realize what the answer is. I think one of the most important things to get across to a particular performer is their point of view. A listener should take away from the demo, obviously, that the actor is skilled and talented and can do a variety of things, or maybe that they only do a few things. But I think one of the most important things is that they get a feeling coming away from the demo that this person has a very particular way of looking at life. If it's humorous, hopefully, then there's the feeling of, gee, not only is the production slick or the acting good, but there's a feeling that this person is a fun person to work with, or that they have a real strong sense of themselves and a strong sense of humor.

I think years ago the objective was to show versatility because there were fewer people in the industry, so each person had to do a lot of stuff. Now you have a lot of people in the voice-over industry, more every day, and I don't think it's nearly as necessary for each person to do so many things. But it depends on the market. There are some markets where versatility makes more sense because you have fewer performers in the market, so each person gets called upon to do many things. Versatility is never going to hold you back. Obviously, it's a plus, and if you do some things radically different from your normal sound, I say put it on the demo. But at the same time, I think the demos that really communicate more clearly and are better sales tools are the demos that bring across this point of view where after two minutes you go, "I think I know where that guy's coming from."

And something else I want to touch on is the word "demo." Really, there's no such thing as a demo when you think about it. Yes, you get this tape or this disk, and it's either stuff that's been on the air or has never been on the air or whatever, and it's supposed to demonstrate the person's abilities. So in a sense it's a demo, but in a sense it's not because these are full on performances. The production is full on, the way it would be on the air, or even better. You will never hear me use the phrase, "It's only a demo." It's much more because as far as that listener is concerned, when he or she hears an audition, even a raw audition out of a booth somewhere where there's no production at all, that performance really had better be all the way.

RAP: Is it okay to put a spot on a demo for a well known national client even though you didn't really voice that national spot?

Peter: I have no problem with that, and I'm going to credit Marice here because I think this is really her feeling and her idea, but I certainly agree with it. A demo is not a history of what you've done. It's not a documentary. A demo is about what you can do versus what you have done. We got a response once from a writer somewhere who got a demo on somebody we had done. He heard his own work and, of course, knew it wasn't a real spot because he knew who did the real spot. He heard the material, and the only comment was, "Gee, I never thought of producing it that way."

RAP: Let's say I bring you several spots I've done already, and I ask you to make me a real nice, creative demo. What kind of creative things do you put into a demo to make it more than just a series of fade ins and fade outs from one spot to the next?

Peter: That can go anywhere from adding music and sound effects that it doesn't currently have, filling it out so that it sounds more competitive and more professional, to just choosing where to cut. Marice and I both tend to like a demo that has a beginning, a middle, and an end. So many demos I've heard seem to start somewhere out of nowhere, go somewhere within that, and then they end sort of abruptly. There's just something about that which sounds very hacked together. I like a demo to have a life of it's own, a beginning, a middle, and an end that tells a little story. I also like to do a lot of little word jokes where a piece responds to copy from a previous piece. Maybe it's a humorous takeoff on the previous piece. I try to give the demo continuity.

RAP: What about intros and outros? At the beginning, would you say, "Here's the voice-over talent of blank blank?"

Peter: No. In fact I would never do that. I believe you just start right in with the piece you want the listener to be hit with immediately. Marice would call it, and this is her word, a "voice print" piece. Often, you'll start with that because, let's face it, that person is who is really going to show up for the session. You might start off with something very strong like that where you get a really good, clear feeling of who this person is, and then go to an extreme from there. Go into a comedy thing that's very, very different, then maybe a dialogue. There's no set formula. Each person is different, and we've produced demos that are radically different from the formula.

Another thing I think a demo needs to do is have a pretty quick rhythm, not so fast that it confuses the listener, but pretty quick. So you don't want to have too many gratuitous bites. Now if it's a promo demo, yeah, of course, because you might have dialogue bites of television shows or movies in there, and there's a reason why they are there. It's context. But in terms of a commercial demo, a classic voice-over demo, if you have a Taco Bell jingle, I don't really feel it's all that necessary to let that jingle sing for five seconds. I think that's a waste of five seconds.

RAP: You must hear a lot of demos people bring that they did themselves or had someone else do. What kinds of mistakes do you hear most often on these demos?

Peter: One big mistake, of course, is saying, "Hi, my name is Bob Smith and here's my demo," and at the end saying "Thank you for listening to my demo." You don't hear it much any more, but I think that's a big mistake. Another mistake might be too much repetition--doing the same type of piece too many times within a demo. Another mistake is making each piece too long. In other words, maybe a person only has half a dozen pieces he thinks worthy of a demo. If I were to cut those half a dozen pieces, I might end up with a minute or a minute and ten seconds out of those six, but he may get two minutes out of it thinking, "Well, a demo is supposed to be two minutes, so I'm going to make this work somehow." I give the audience a lot of credit, and I think they know after fifteen or twenty seconds at the most what the spot is about, what the performance is about, and now they're ready to move on to something else.

RAP: Do you get involved in the packaging of the demo?

Peter: No. Marice occasionally will suggest...actually, pretty often she'll suggest an idea for packaging or a concept, and those are usually brilliant, by the way. Then they go to an artist, or she'll recommend an artist, and they'll go from there. Neither one of us is an artist in that sense.

The packaging is extremely important. In fact, Marice likes to tell a story about a question she asked somebody at an agency once. They had all these tapes up against the wall, and she said, "Gosh, how do you deal with all these tapes? Which ones are you going to listen to? Which ones are you going to take seriously?" And, essentially, the answer was the ones that have four colors and look like they belong to people who are players. The ones with a little typed label on a white background, they may be the next Orson Welles, but it would be hard to tell from the packaging. And let's face it, it all works together. When you see a professional package and put the disk on and listen to it and say, "Yeah, this really lives up to the packaging," that's really a double punch.

RAP: Tell us about the studio you're working out of?

Peter: Let me go back for just a moment and give you a bit of technological history first. I was one of the very last analog holdouts. I am working digitally, now. I do have a workstation, but I was very late to come to it for a number of reasons. I really loved the sound I was getting with analog. I was used to it, and I stayed with it for a long time. And I will never put that down. Obviously, times have changed and technology has moved along, and I found a program I'm using that I absolutely love. It's SAWplus by Innovative Quality Software. This thing is terrific. First of all, it's extremely inexpensive considering how powerful it is. It's very, very well thought out. The man who wrote this, Bob Lentini, has been an engineer for many, many years himself, and what intrigued me about it was that for a guy like me who was thinking in terms of analog and splices and reels going around, it was not a big leap into this digital world as it is with some other programs.

I have my little setup here at home, and all the editing and mixing is all done within SAWplus. I have some outboard gear that I use for things like reverb and digital delays and things like that. I also have a few auxiliary programs that I use mainly as processing devices. I'll build everything in SAWplus, but then I'll take a mix that I've created in SAWplus, for instance, and bring it into another program called SoundForge, which is pretty well known. I'll use SoundForge basically as a processor because it does some things that SAWplus doesn't do, or it does them differently.

But I'm fully digital now, and I do hear a difference in sound quality. I mean, 16-bit digital audio is not what analog is in terms or resolution. And the other thing about analog that digital just doesn't have is the ability to use the medium as part of the sound, as part of the palette. All of us engineers who grew up with analog tape know this, that as you hit a piece of tape with any sound, it never comes back the same way it went in. Most of the time it comes back fatter and rounder and a little more pleasing to the ear, and there's something about that which is very nice. It's a form of distortion, but it's a pleasing form of distortion. So when you start working fully digital, you start to miss that, and you start to find ways that you can fake that. I don't actually fake it. What I do in many cases is transfer stuff to analog somewhere in the process and get some of that analog grunge, as it were, into the equation because it's a familiar sound.

RAP: My ears are probably not as good as yours, perhaps mainly because they've been trained on radio with all it's limitations and processing. The difference I hear between analog and digital is that there's no tape hiss on this digital recording and it sounds crystal clear. I like that, and that's pleasing to MY ear. But I don't call what I hear in the analog world, "warmth," and I haven't found it to be more pleasing than a clean digital sound. I wonder if people who like that "warm" analog sound are simply used to listening to distortion and tape hiss as opposed to a pure replication, so when they hear the pure digital recording they go, "No, this isn't right."

Peter: Well, the answer lies somewhere in between the extremes. Digital is not perfect, and it has it's own forms of distortion, especially the lower end of digital. All digital is not created equal. If you go out to Circuit City and buy a $99 CD player and you compare it to a $900 CD player, you probably will hear a difference. The quality of the digital conversion in there is really different, and cheap digital usually has kind of an edgy, metallic sort of quality to it.

You're right. A lot of people probably can't hear the difference just like maybe I wouldn't be able to see the difference between a Mitsubishi TV and an RCA. I don't know. Maybe I could. But in terms of audio, my ears are very, very sensitive. I don't think that it's just that they're not used to listening to perfect reproduction or whatever you want to call it. Actually, I think that there are a lot of folks who hear the fact that there are big holes, literally holes, in digital reproduction because there are only so many samples that go by in a given period of time in digital. It's an on/off phenomenon. There's a sample. There's no sample.

RAP: Even at 44,000 times a second you think they perceive the holes?

Peter: That sounds like a lot, but it's not. We haven't even begun to understand what we can perceive. They say most human beings hear only to a certain frequency. Well, they did some tests where they played music for people and had super tweeters on that reproduced frequencies thought to be out of our range. They attached electrodes to these people and looked at the brain wave activity. They found that as they turned the super tweeters on and off, the brain wave activity changed. So we are perceiving things they say we can't perceive.

Basically, I straddle the fence. I know that analog has a great sound and a lot of resolution, and when it's properly used, it can sound absolutely marvelous. So can digital if it's properly dealt with, as well. And having done live music for over twenty years, I can tell you that the difference for me is that when you go to analog tape, the tape is part of the sound. And you know that when you record a certain instrument or a certain vocal to that tape, when it comes back, it's going to have a different sound than when it went in, and you must plan for that. When disk mastering engineers made vinyl records, they really had to work with that because as soon as you put something into a groove on a record, it changes quite a bit. Now, in the digital domain, since things are much more accurate to the way they sound when you put them in, if you want a warm sound for instance, you've got to engineer that in because the tape isn't going to give it back to you.

Now, it's pretty well known, and I've experienced this: if you increase the sampling rate, and if you increase the bit rate from sixteen bits to twenty or twenty-four bits on a digital recording, you get a greater resolution and it sounds more like analog. More like analog in the sense that there's more depth and greater detail.

RAP: That would explain a couple of new DAT machines out there that are sampling at 96kHz.

Peter: Yes. I haven't heard them, but that's what they're trying to achieve. I've got a friend with a Nagra D, and that's probably one of the best digital recorders in the world right now. Nagra is very well known for making tape recorders for the film industry, and they are very, very expensive precision made machines made in Switzerland. They make a digital machine now that is a reel-to-reel, but it's digital. It will record four tracks of digital audio, and I think it's a twenty-bit format. All I know is that it sounds marvelous.

I'm working with workstation that is 16-bit with a 44.1 or 48 kHz sampling rate. So it sounds basically like a CD, but I'm very pleased with it. I bought a very good sound card for it, but I hear the limitations. But, and a big but, I think if you know what you're doing and you know the limitations of your gear, you can get a good sound out of almost anything--almost. So I've managed to work my SAWplus into giving me as close to my old analog sound as I think I can get with it. In some ways it's better because, as you say, there's no hiss and wow and flutter and stuff like that.

RAP: Especially with your twenty-plus years doing this live show at the station, you must have miked a bunch of voices for singing as well as voice-over, not to mention a variety of instruments. What kinds of mikes do you like to use for voice work?

Peter: Well, there's no clear-cut answer. In fact, when I do record people, I'll usually bring a whole arsenal of mikes, and I'll try different mikes for different spots depending on context. For instance, if it's supposed to be a television kind of thing, maybe even an on-camera kind of a sound, I might use a Sennheiser 416 shotgun mike pulled back a little bit to hear just a little bit of the room and get kind of a boom mike sound. On the other hand, if I have a cosmetic piece or a car piece where I want a lot of intimacy and I want the voice to be big and resonant, then I'll go the other end of the spectrum and use a large capsule condenser mike like a Neumann U87 or a TLM 170 or an AKG 414, something like that. Sometimes I'll put up a dynamic mike, a much less expensive dynamic mike that will give me a harder, less professional sound, but it may actually work better for what I'm doing. Part of it is that I'm trying to bring out different aspects of the voice, and I'm also trying to fool the ear a little bit. If every piece on the demo sounds exactly alike, it's kind of a giveaway that this demo was created in somebody's garage. So part of what I'm doing is creating the illusion that these pieces were recorded over a period of time in different locations.

RAP: What about processing on the mikes?

Peter: First of all, you start with a good mike, of course, and you put it in the right place, hopefully. Then the next very, very important thing that a lot of folks overlook is the microphone preamp. What is the mike looking into? My experience has been that you can take a really wonderful microphone and plug it into a really average sounding mixer or tape recorder and wonder, "Gee, how come this sounds so grungy?" It's because the mike preamp itself is really not up to the task. They can generate a lot of distortion, and once you've generated that distortion, that's it. It's on your tape, analog or digital, and you're stuck with it. By the same token, you can take a $50 microphone from Radio Shack and plug it into a really wonderful mike preamp, and you'll hear stuff coming out of that mike that you didn't think the mike was capable of, but it is. I mean, it may not be a great mike, but it's a decent enough one that the mike preamp is able to bring out detail that you didn't think was there. So the mike preamp is very, very important, and when I record folks for demos, I will bring in either a very fine outboard solid state pre or vacuum tube pre. I've got a friend named Steve Barker who has designed a series of professional units--preamps, limiters and equalizers--that are all vacuum tube based. It's called the VacRac Line, the Inward Connections VacRac Line, and it's all vacuum tube from beginning to end. This is some of the finest stuff I've ever used.

RAP: So, start with the right mike and use a good preamp. What's next in the chain?

Peter: Once you're actually producing the material and you're able to process or not process, then it's kind of a matter of choice. I'm not of the school that says you always want something that sounds accurate. I think accuracy is not always appropriate, especially in voice-over. First of all, all microphones lie. None of them tell the absolute truth. Some are more accurate than others, but none of them are completely honest. So I choose a mike and a processing chain that flatters the voice rather than producing it accurately because sometimes you'll get an artist who has a little edge in his or her voice, a little something that is a little rough on the ear, and I don't want to necessarily reproduce that completely. Maybe I want to minimize that. Maybe I want to give a little more body to the voice and a little less edge on the top. So I'll choose the right microphone and use the processing to push forward the part of the voice that I want to push forward. We're always trying to flatter the voice. We're trying to show it in the best light.

RAP: Are you talking about EQ here?

Peter: Well, sometimes. A little EQ goes a long way. If you're trying to do an extreme effect like a phone filter effect, yeah, you need a lot of EQ. But in terms of just doing a full-range "here's the voice" kind of thing, I don't use a huge amount of EQ. I do like to mess around with different kinds of limiting and compression because changing the dynamics of any sound, voice or other sound, does change its character a lot, and I can do a great deal with compression and limiting. I will use reverb in very subtle ways sometimes, ways where if you listen to it mixed with the music you might not even be able to tell there's any reverb there. But if you remove it, you will hear a difference. There will be a sudden lack of depth to it or a sudden deadness to it if you don't have it there. And I like things like Aphex Aural Exciters which add upper harmonics to things. I also tend to de-ess tracks quite a bit because in the commercial world, there's really no such thing as too bright, and the problem with that is that if you keep brightening a voice, eventually those sibilant sounds are going to come out and bite you. So if I have somebody who's even mildly sibilant, I will de-ess the voice before I brighten it up.

RAP: It sounds like you record the voice flat and save any dynamics processing and EQ for later.

Peter: Well, I wouldn't go quite that severe with it. What I do is record with a great mike and a great preamp, and I have a limiter in the line at all times. I may or may not be using it depending on the talent or the spot. More often than not, I am using it but in a very lightweight sort of way because I don't want to paint myself into a corner later when I might hear a track that's overly compressed and then I'm stuck with that. I'd rather do it post where I have control. I'll use the limiter when I record as a safety net because sometimes a performer will get kind of excited and suddenly deliver a phrase or a word a little louder than you expect it. The limiter is there just to give you a little bit of protection in case the performer runs into the red because on a digital recorder, as you probably know, as soon as you go into that red zone, you've had it. It's not like analog where it distorts gradually. But I do save ninety-five percent of my processing for the post session.

RAP: There's a sound I hear on demos from the big boys from time to time. It's a processing that has the bottom rolled off, and the voice will just cut through anything. It's like the guy is right on top of a cheap mike, though it's not muffled at all. It's almost always on a huge national spot, maybe a movie spot. What are they doing?

Peter: I know what you're talking about. There's a couple of things going on there. First of all, it's about intelligibility. If you've got a busy mix going on, from a busy music track with horns and strings to a music track with lots of sound effects and the whole nine yards, that voice has to cut through a lot of stuff. There are really only a couple of ways to make that happen. One of them is to compress the voice so that its dynamic range is very small. Therefore, it will sort of sit on top of all this stuff going on around it. The quieter words will not be quieter anymore, so they won't get lost in the mud of everything that's going on.

Another thing that goes on is if you take out the bottom end and accentuate the upper mid-range of a voice, it may sound sort of sharp and shrill to you, but at the same time it increases the intelligibility factor, and after all, that's what it's all about. They want to get that message out there. So usually it's a combination of compressing all the dynamics out of the voice and brightening it up almost to the point of pain, and that will give you the ability to mix music and sound effects up fairly loud and create a very in your face sort of sound. And for a lot of advertising, that's just the way things are supposed to sound. I'm not saying I agree with it necessarily, but that's the sound. That's what radio stations seem to be vying for all the time. They want to sound louder than the competition. They want to sound brighter and more in your face than the competition so that when you stop on that station in your car, you don't necessarily know what's different about it but you know that somehow you hear the lyrics a little better and everything seems to sparkle a little more or whatever. You'll tend to stay on that station because it sounds better in a noisy environment like a car going down a freeway. It's about intelligibility.

I think what happens is that engineers and producers sit in a room for too long. I know I did. After a twelve-hour day as you're mixing the last spot, your ears are gone. Your judgment is gone, and what you heard six hours ago is not what you hear now. So suddenly the producer is turning to you saying, "Can you understand when he says 'Chevy' there?" And you say, "Oh, I don't know." And he says, "Can you brighten that up a little bit?" And before you know it, suddenly it's popping out beyond belief. But again, it's because your judgment is now gone. I've made mixes and come back the next day, and I'd be aghast at what I did because I couldn't hear any more. That's true in any field. There are only so many useful hours in a day. I know that when I'm producing demos, I can work for three or four hours straight. After that, I've gotta get up and move around and get away from the computer and take a walk or do something, preferably something quiet. Otherwise, I have no idea what I'm doing, no idea whether this is the tape I want to use or that's the music I want to use. My brain is gone.

RAP: How about a couple of production tips before you go?

Peter: Having all the bells and whistles is great, but what's important is the idea and the creativity. Know the limitations of your gear, and be true to the idea. Don't spend so much time doing gimmicky things with the equipment. Also, the real star of any demo, no matter how much I want to produce a piece, is still that performer, and sometimes I have to pull back from a lot of processing and a lot of bells and whistles in a production because I'm getting to the point where the production is becoming the star and not the performer. It's very important to know where the line is.

Something I do when I'm producing a piece is listen very, very carefully to the rhythm of the piece. Everybody reads with a certain rhythm, not just the rhythm between lines, the pauses they take, but the intrinsic, internal rhythm, as it were, of the read. When I find a piece of music for a spot, I'm really scoring that spot. I'm really creating a very tight relationship between music and voice. And I tend to build my spots in such a way that I have a piece of music driving it, and then I lay the voice-over in line by line and get a rhythm going, a relationship going. That, to me, is a big part of my sound. I think a lot of radio people certainly already know this, because after all, their business is music. But that really drives a lot of my production, rhythms of all kinds.

RAP: What's down the road for you? Any plans?

Peter: At this point I'm trying to keep up with the demand. Marice and I have a waiting list now. I don't aspire to go back and do what I've done, to be an engineer in a facility somewhere. I've tried television and that didn't really thrill me. I don't really have a great interest in working in commercial radio having been brought up in noncommercial radio, a little bit spoiled as to what the possibilities of radio really are. I think I would feel kind of limited in commercial radio. So I don't know. I guess I'll just look for ways I can exercise the most creativity and have a great deal of independence. Of course, that's a tall order.

RAP: It sounds like making The Demodoctor a huge success would be a great future for you.

Peter: I would love it. I get a great deal of satisfaction out of supporting artists both in the voice-over area and in music when I do my radio show. I'm not being paid for the show, but what I'm doing is live mixing. I'm creating a live radio show and a tape that really flatters their music, and that is just very, very satisfying to me. Having been a performer myself--I used to sing and write and play gigs when I was in my early twenties--I relate to artists of all kinds. I feel like I know what the process is that they go through internally, so I feel like I have a handle on how to present them.

♦