by Jay Rose

I’ve always loved radio. Since I’m not great air talent, I found my niche producing radio spots for ad agencies. Computer editing let me do sound for their TV spots as well, which was fun… and led to longer sales films, training videos, and some simple TV shows.

Then an agency producer asked me to supervise the track for a film he’d written—an actual movie, starring Sally Field and distributed by MGM. Talk about a learning experience! A 100-minute film is way bigger than a hundred radio spots, and not just because it has pictures. Expectations are higher, everything is more exacting, but there’s a chance to really move people. And there’s more money.

What’s also different is the audio tricks and techniques used in the feature film world… many of which translate nicely to smaller projects. For a radio producer, this can be a major win: you can use some of these techniques in your radio assignments, do a better job with the station’s promo videos, and—if you’ve got the time and inclination—start doing freelance work for local filmmakers.

But bear in mind, this article has room for only a few of these techniques. And I’ve limited it to post-production, audio work after the video is shot and edited, because it’s similar to radio production. Location recording is a separate specialty.

First, some of the technical stuff

So: pictures have been shot and edited. On-camera dialog from individual camera angles has been assembled simultaneously with the picture. That dialog track might sound like an audio ransom note, since each angle or location probably had a different mic position and background noise; even two close-ups in the same scene might have been shot hours apart.

You’ll want audio software with some way to display picture, rather than doing sound in the video editing program, because most video software forces you to edit on frame boundaries. Those are just too far apart—1/30th second—for tight dialog or music cutting. Good audio programs also let you organize lots of tracks, as many as a dozen just for on-camera voices, plus dozens more for sound effects or music, and route them through different submasters and processing chains. They let you lock the timing of some sound clips while moving others, so you can edit freely any time you don’t see characters’ lips. And they accept specialized OMF or AAF files from the video editor, which not only keep track of sync but also let you refine the existing edits. Those formats let you sort a single track from the editor into separate tracks for each character, a very powerful technique.

ProTools|HD and Nuendo are the gold standards for audio post software, with power and efficiency that justifies their high prices. But you can probably get started with any multitrack software you’re using now, if it supports pictures. Or investigate Reaper (www.reaper.fm), which—if you’re technically minded and have some extra time—does almost everything you’ll need for as little as $60. If your software doesn’t speak OMF or AAF, check AATranslator (aatranslator.com.au), a $200 Rosetta Stone for sound files.

Splitsville!

The main technique that separates film or video dialog from other voice production is the track splitting referred to above. It lets you hide the inevitable jumps in timbre and background sound, when a morning’s worth of out-of-sequence shots is combined into a single scene. It also simplifies and speeds up the mix, because you can preset faders and plug-ins for each character or setup, giving each the processing needed to make a consistent whole. It lets you mix while listening to a scene the way an audience would, instead of trying to catch each picture edit while riding a single fader.

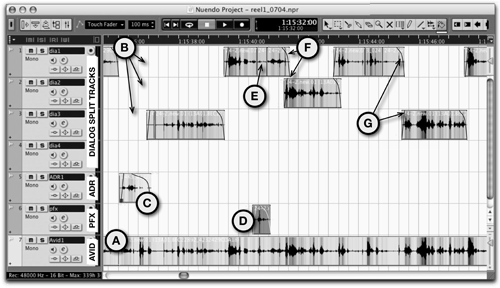

The screenshot shows track splitting in a fairly simple scene, with three characters and a couple of close-ups. The bottom track (letter A) is how the video editor cut the scene and passed it to me via OMF. Letter B shows where individual lines have been copied and pasted among the top three tracks. One line has to be replaced with a studio recording—it’ll need a lot of processing to match the location recording—so it’s separated at C. An actor slams a door in the scene; that sound is moved to an effects track (letter D) so we can lower its volume as needed. We added room ambience on the dialog track (E) where that slam used to be: that continues without being lowered, so the background remains steady.

Note how most clips overlap slightly (such as at F), even though these were hard cuts on the original. One of OMF’s and AAF’s tricks is letting you extend a clip longer than picture editor had it, without having to go back to source material. The curved lines over the ends of most clips (G) are fades, using those extensions. When we play the scene, the fades combine into smooth transitions between clips. Many good audio programs can add these fades automatically.

Track splitting is a killer technique, and I use it almost any time I’m working against picture. It’s much faster than applying a corrective process to each clip separately, it’s easier to change the processing when needed, and it usually leads to a smoother mix. Also, you can do the splitting almost anywhere. All it needs is a laptop with compatible software, and a pair of headphones. You’re not making processing decisions, so you don’t have to tie up a production studio’s monitors for this operation.

Sound effects can be easier in the video world

Ever get stuck trying to create an obscure radio sound effect that’s instantly recognizable, and doesn’t need to be identified by the talent? In video, the viewer can see what’s supposed to have caused the noise. That sells the sound effect, making it easier to accept as real. For example, I needed expressive rodent squeaks for comic close-ups of the animal star, in a promo for the movie Mouse Hunt. Nothing in my library worked with its head movements. So I rubbed a balloon in front of the mic. A few tiny moves in my DAW, and mousie learned to talk!

The same principle can hold for rustling clothing, most footsteps, small machines, and—as we’ve all seen in the ‘making of’ documentaries—using antenna guywires for light sabers.

How to mix a video

Make all the edits first. Editing is done in bits and pieces. Then mix, which is always best if you’re listening to the emotion or a scene’s message in a continuous flow. Once you’ve done that, feel free to tweak little pieces of the mix by manipulating its automation. The overall sweep will still be there.

When you’re ready to start mixing, turn off the music and effects! Mix the dialog by itself, first. Make sure the voices sound natural, and all the separate track processing combines to a believable whole. This is so important that Hollywood calls this first step the dialog pre-dub, and most films mixes spend at least half their studio time getting it right.

Then add the effects and music. If they start fighting dialog, process them or lower their volume. Or try sliding them a fraction of a frame or two… sometimes a tiny sync adjustment can make everything play together nicely. But whatever you do, don’t equalize or compress dialog to ride over the music or effects. That can make it unnatural, destroying the viewer’s emotional experience.

The last step? When you think you’re finished, take a long break. Then gather all the stakeholders (director, producer, whoever), darken the room, and play the whole show without interruptions. Watch it the way an audience will. Put up a timecode window, and tell everybody that if they see something they’re not sure of, they should write down when it happens. Afterward, you can go directly to those sections and make the changes that make your client happy.

How to get and keep the work

I’ll repeat that last line: make the changes that make your client happy. This has to be your attitude throughout the entire process. If the director wants to do something you think is wrong, say so. Present your argument. But argue it just once, and wait for their decision. A movie can have only one director, and this isn’t your movie.

Do your job right, present good solutions in a way that clients can see improves their project, and they’ll call you for the next one. You’ll have the thrill of seeing your work on a screen. At the end of the film, you’ll even see your name on the screen… with a bunch of others, since movies are a collaborative effort. Come to think of it, that’s more credit (and likely more cash) than you get with a radio spot.

Fadeout

There’s a lot more to film and video sound than I can fit in a couple of RAP pages. So I wrote Producing Great Sound for Film and Video, which covers the whole process. The fourth edition was just published by Focal Press and is available at Amazon and other booksellers. More info, downloadable samples, links to discount sales, and other nice stuff is at GreatSound.info.

♦

Jay Rose (