We anticipated that few of our readers have time to “dabble” in sound design, and if they do, they probably don’t have much time to write about it. But we did get a few commendable responses from some noteworthy gentlemen, some of whom are quite familiar with the subject. Thanks guys!

We anticipated that few of our readers have time to “dabble” in sound design, and if they do, they probably don’t have much time to write about it. But we did get a few commendable responses from some noteworthy gentlemen, some of whom are quite familiar with the subject. Thanks guys!

Q It Up: Do you dabble in sound design, or are you pretty much the type that just grabs the sound effect from the imaging effects or sound effects library and lay it in? If you do sound design, what are some of your favorite tools for creating sounds? Do you like to take existing sounds and alter them? What techniques do you find yourself using most often?

Jim Kipping <jim[at]jimkipping.com>: When digital technology now fits in your hand, why not Foley your own stuff?!? I needed a “rooting around in the fridge sound” for a specific spot. So I loaded up my gear in hand and went down and… wait for it… ROOTED AROUND IN THE FRIDGE DOWN THE HALL! Took less time than weeding though thousands of sfx and trying to find the right one (much to the chagrin of Sound Ideas in Canada).

Blaine Parker <bp[at]slowburnmarketing.com>: “Dabble” would be the operative word. I’d hardly call myself a sound designer. But sometimes, you have to go there.

There are plenty of times when I want a sound effect that either doesn’t exist under the name of the effect I’m looking for, or else if it does, it doesn’t sound nearly as impressive as it ought to. For instance, we once needed the sound of a cell door sliding shut for a county sheriff’s political spot. The actual “cell door” in the SFX library sounded more like the click of the latch on a kid’s playpen door. We ended up assembling an effect from various metallic sounds (like “banging on metal pipe” “rolling metal cart”) that had nothing to do with “cell door.” You just ask yourself, okay, forget the name of the effect, what are the actual physical components that would create a sound that makes sense? Once, when I needed various absurd sounds representing grinding and failing transmissions, it became a search for an array of over-the-top, crashing metal debris sounds and layering them together.

I’ve also always loved Foley, and will play with objects to create sounds that don’t exist in the library. My first experience with this was when Jay Rose was creating a radio promo for a PBS show, and he needed the sound of paleoanthropologists sliding aside a slab of stone. I bumped into Jay as he was rushing into his studio with two stoneware coffee mugs that he was about to grind together in front of a microphone. The resulting sound had all the weight and gravity and abrasion that it needed. Between that and having been on the Foley stage at Skywalker Ranch (which is filled with more kinds of miscellany for making sound effects than you can possibly imagine), I realized early on that if I ever needed a sound effect, the radio station kitchen was often a good place to go looking for it. Pots and pans have found their way into the studio. Mixing spoons and spatulas. Coffee mugs and salad bowls. Celery stalks and carrots. Cracker boxes and candy wrappers. I’ve bought bags of chips from the vending machine to get crunching and pouring effects. I also used to keep all kinds of crap in my desk, and you never knew when something from there might end up behind a microphone.

And in a pinch, when there’s no alternative, vocalized effects can do the trick. Just the other day, I needed a cartoony “thwip!” for a client’s video. The cartoon SFX library didn’t have it. So I went into the booth and made a variety of percussive articulator noises, played with the pitch and time compression until it sounded right and voila — custom sound design. Cha-ching!

John Pellegrini <pellegrinijohn[at]gmail.com>: When I was in radio day to day I had many opportunities to create sounds for specific instances. One example has always stood out for reasons that will immediately become apparent. A station I worked for had a client who was advertising a special product he’d invented - a special cover that you place on your car during hail storms to prevent damage. I’ll let the reader ponder the completely ridiculous premise of that product (and yes he didn’t sell a single one of them). Beside the point of the stupidity of the product, he ABSOLUTELY INSISTED (the caps were written that way on the prod order from the sales rep) that the commercial had to have the “sound of a hail storm hitting the surface of a car”.

The fact that none of the sound effect libraries we had in the station contained such a sound was no excuse as far as the client was concerned. He was paying big bucks for the advertising campaign and the spot had to be done as demanded or he would not buy.

Fortunately I must have been in a particularly inspired mood that day because I instantly decided that glass marbles being dropped on an empty metal tape reel canister cover laid on the carpeted floor of the prod room would make a close enough resemblance to the sound. So I walked down the block to the local drug store, bought a bag of marbles for a buck and recorded. Spot was approved, on to the next mess.

Though to be perfectly frank, the one sound I wished I could have recorded many times over would have been the sound of me applying a baseball bat to the side of certain client’s heads. But I have always refrained owing to a high sense of professionalism.

Michael Pedersen <michael[at]redfm.ca>: I am a formally trained audio engineer and had always “followed the rules” of production. Certain things go certain ways; it’s just the way it is. That is until I decided to take a short course on “noise music” at a local art school. I joined the course because I thought it might be fun to see just what “noise music” was. Ended up that I was the only person who had actual audio engineering training, the rest were in fact “artists” who believed that what they were doing was making music. I watch classmates plug all the wrong things into all the wrong inputs of various devices, which then made all the wrong noises. To my amazement, my classmates thought that what they were doing was awesome, even musical. I soon realized that all of my training was in fact very limiting, as I had never stepped into this world of sound experimentation.

Taking their lead, I begin to play around with feedback loops, distortion, and sometimes, quite painful sounds. I began to sample all of the random signals that I was getting out of the gear and making music out of my rapidly growing database. Unlike my fellow students, I could actually go quite further with this noise and control it in different software environments. The problem I soon found was that acquiring crappy old gear to sample became time consuming and made a mess of my studio. I was still inspired however so that’s when I decided to apply the same experimental technics in the software world using Propellerhead’s Reason.

Going one step beyond simple audio routings, I could control and manipulate a vast number of parameters using control voltages. I could make the synths and effects devices in the Reason rack go absolutely crazy, then sample the results and further expand my sound effects database. The advantage of sound design in the digital domain is that you have no noise floor. You can compress or normalize the crap out of things, and you are not bringing up unwanted noise. Sometimes, I’ll set up a basic synth patch in Reason to modulate, record the output, then normalize the sections of the audio that were “flat line waveforms” or what you would have previously thought was nothing but silence. In fact, at a very, very low level, the synths are outputting crazy sounds and you can use extreme normalization on those sections because there is no unwanted noise in the signal. When you bring it up by 100dB, you often get crazy sounds that you can then edit into imaging sounds. In a nutshell, that is my technique.

In Reason, some of the best Rack Extensions (Reasons version of plugins) for sound design are Echobode, BV512 Digital Vocoder, Polar Dual Pitch Shifter, Neptune Pitch Adjuster, and the list goes on! Malstrom is my favorite Reason synth for sound design and manipulation but they are all very good. I highly recommend Reason for sound design -- it’s affordable and if you understand signal flow, it’s easy to use and manipulate while sounding fantastic!

You can check out my imaging libraries at www.distinctbroadcasting.com.

Jay Rose, CAS < jay[at]dplay.com> Clio- & Emmy-winning Sound Design, www.dplay.com: Tony Schwartz, who pretty much invented the field of advertising sound design, rarely used sound effects. He said “People ask me about ‘sound effects’. I tell them I prefer ‘effective sounds’.”

For him the design of a spot was primarily the words and how they’re said... including how the rhythms of the spot reinforced or minimized concepts, and ultimately how the message could be designed to work with thoughts that were already in the listener’s brain.

Tony wrote and designed the famous “Daisy Spot” for the 1964 presidential election [http://youtu.be/dDTBnsqxZ3k]. It used sound effects of birds and an explosion to set scenes, but the key emotional message - and the sound design - was a simple set of spoken numbers... counting up to ten and back down again. The spot aired just once, and is still cited as one of the best negative ads ever created. Schwartz pointed out there wasn’t a single negative word in it.

He also created what’s generally thought of as the first spot where an announcer says multiple words simultaneously, for the movie “Woodstock”. It’s a common multitrack technique now, but for him it required multiple rolls of 1/4” tape, with each overlap carefully timed and blade-edited. More importantly, he devised a way of analyzing which words could overlap, and which didn’t need to be heard much at all because they’d be completed by the listener’s brain.

That’s sound design.

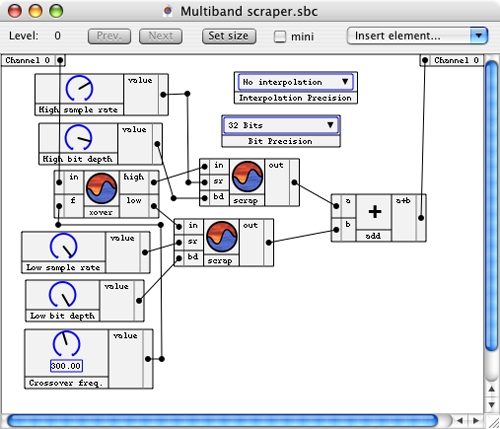

For the record, I usually use Sonic Birth for designing unusual sounds or processors. It’s a freeform (and free!) DSP tool that lets you string modules together, fine tune them in real-time, and then generate a VST or AU plugin that loads into your workstation. Sci-fi generators, unusual harmonic shifters, frequency-dependent delays, or practical devices like 16mm projectors and bad cell connections... it’s like a virtual Eventide H8000 Orville, without the hassles of patching in extra hardware. (Anybody want to buy a slightly used Orville?)

Joey DiFazio <Joey.DiFazio[at]siriusxm.com>, Sirius/XM, New York: I view every session as a work in progress. My better pieces are usually done with effects & mixes that I’ve used many times before. I just keep tweaking them to perfection and spinning off new variations. I stick with the proven winners - that is, the newer effects and transitions that I create almost always need to catch up to the quality of the proven ones. Very few times does a project built from scratch come out as beautifully as a project created with finely tuned, premixed transitions and effects. Also, I never use effects just for the sake of using effects. I only use what I need to highlight copy and transition to ideas. My feeling is, there should always be a reason why effects are in the mix.

Dave Spiker <davespiker[at]aol.com>: Sound design is definitely on my plate. I have recorded my own SFX, and used SFX libraries. I like SoundDogs online library. Use it a lot currently. But I make use of whatever is at my disposal so I can reproduce the sounds I’m hearing in my head. Just like with movie sound design, I break things into dialogue, music and SFX. Everything must coordinate to complement the other elements.

We interviewed a former Navy Seal who authored a book about his experience. He told of one night his team was ambushed. He gave great descriptions of bullets flying, bad guys on roof tops, good guys pinned down, pulling the Humvee up as a block for the rescue. So I went crazy with the audio atmosphere to undergird his story. He later told me, when he heard the final audio, he felt like he was right back in Iraq. The nicest compliment he could have paid.

I’m attaching and MP3 of that mix, just in case you’re curious [featured on this month’s R.A.P. CD].

David Boothe <DBoothe[at]hopefortheheart.org> Hope for the Heart, Inc.: I don’t do much sound design any more, although I used to do quite a bit 10-15 years ago.

My primary tool was Csound (http://www.csounds.com/about), a free but extensive software synthesizer. The learning curve can be quite steep. But if you’ve ever worked with modular analog synthesizers, you’ll have no problem with Csound, conceptually. You’ll just need to learn the language.

More often than not, I started with real sounds, either from a SFX library or ones I recorded myself. I would then use Csound to modify, twist, bend, shape, and mangle them.

With the increasing horsepower of modern computers, Csound can often produce real-time output. However, it still has the basic operational concept of rendering sound to disc based on instructions from two text files that you, as he sound designer, write. One file is the “orchestra” file where “instruments” are designed and created using various Csound generators, modifiers and other opcodes. The second file you write is the “score” file that tells the instruments in the orchestra file what to do. The beauty of that is you can save individual instruments or even entire orchestras for use later with a different score.

Of course, this means you cannot hear what you are doing while you are doing it. You must write (and debug!) the files, render them, and then hear what you’ve created. To me this has a real advantage: it forces me to think carefully about the end result I want, how I can get it, and then go about doing that, rather than wasting time turning knobs and pressing switches, hoping to get lucky. I can think of a lot more fun ways to waste time than that.

♦