By John Pellegrini

“Los Angeles. He walks again by night. Out of the fog, into the smog…” Thus began my very first encounter with a group of gentlemen who called themselves the Firesign Theater. It was 1972 and my friend, who was playing the record on his home stereo, had told me that this group was “really funny”.

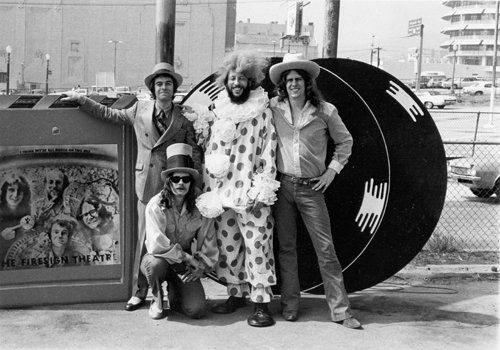

Those two words, “really funny”, hardly did justice to what I heard. The Further Adventures of Nick Danger, Third Eye wasn’t just a parody of radio detective shows, it was a mind-opening revelation about the power of imagination and a perfect illustration of how radio was so much better suited than either television or cinema to probe into universes beyond our own. From the crazed mystery in the plot that’s so impossible to figure out it that it takes an interruption by FDR to bring the story to a close, to the ridiculous parody of a 1940’s era radio commercial (“Loosner’s Castor Oil Flakes, with Real Glycerin Vibrafoam!”) to the perfect inclusion of cheap Hammond organ thriller music, you realize that this sketch was even BETTER than anything produced from radio’s golden era. These four guys (“and a couple a gurlz” as it stated in one of the album liner notes), Philip Austin, Peter Bergman, Phil Proctor, and David Ossman had created something that truly amazed me, and from that instant I knew what I wanted to do when I got into radio.

You see, I had always wanted to go into radio because I liked the idea of being able to be well known without the majority of people knowing what I looked like. The mystery of those voices I heard on the radio was part of the appeal. My dad was a big Stan Freberg fan and we would laugh at his recordings. I knew about Orson Welles and the War of the Worlds, and a lot of other radio comedies from the so-called “Golden Era”. There were other radio comedians that had record albums out as well, like Bob & Ray and Hudson & Landry. But there was one common thread through all those entertainers, as well as all the radio shows: they all had humor based in solid reality. Not that there was anything wrong with that, it’s all very funny. Another common thread with the comedy records back then: they were all either performed live with an audience, or had laugh tracks inserted like most television shows today.

But when I heard Nick Danger I heard something that was not of this earth. I heard alternative universes where anything was possible, and not just because someone said it was possible, but also because it was so well performed that you actually believed it to be true. And just as importantly, no laugh track; no audience to tell you something was funny, and thereby interrupt the reality. You instead discovered on your own that something was hilarious, as if it was a shared private joke between you and the performers. Yes I know FST was not alone in this; Stan Freberg and Bob & Ray’s recordings were also free of laugh tracks. But they did shorter sketches with sound effects and musical stings to let you know you heard something funny. Punching the punch line so to speak, the standard humor format. Not that there’s anything wrong with that, I am a huge fan of Freberg, and Bob & Ray. I’m just demonstrating the difference between the way things were done and how FST broke beyond that capsule of expectation.

Right after listening to Nick Danger I went to the local record store and bought the first four albums in the Firesign Theater’s collection. The titles alone told me that something new and special was contained on those records: “Waiting For The Electrician Or Someone Like Him”; “How Can You Be In Two Places At Once When You’re Not Anywhere At All”; “Don’t Crush That Dwarf, Hand Me The Pliers”; and “I Think We’re All Bozos On This Bus”. The album covers had interesting artwork with them… perhaps the best known of them all is “How Can You Be…” which has become better known by the second title “All Hail Marx And Lennon”, with the pictures of Groucho Marx and John Lennon, and the members of FST in typical Soviet military and politburo style garb saluting underneath. Revolutionary at the time it was made, and still a provocative pun today.

The first album contains three short sketches, including Temporarily Humboldt County, which is one of my favorite takes on the plight of the American Indians and which I always made a point of playing on Thanksgiving when I was an on-air disc jockey. The flip side of the album begins the start of a long form stream-of-consciousness sketch of a single man and the strange things that happen to him, which is then continued on the next three albums with each member of FST taking the role of the protagonist whose name and story changes each time as well.

Large amounts of study have been written about the group’s first four albums and their subsequent works as well, and I don’t need to get into much of the meanings of any of the work here. Rather, what I want to do is talk about something more personal. When I think about the people who inspired me, the Firesign Theater is at the very top of the list. It was through them that I learned about Spike Milligan, who was their inspiration, along with Peter Sellers, Harry Secombe, and the Goon Show. After the Firesign Theater I found out about Monty Python, who seemed to me at the time to be an English version of FST (I didn’t learn about the direct connection between Python and The Goons through Beyond the Fringe until later).

Large amounts of study have been written about the group’s first four albums and their subsequent works as well, and I don’t need to get into much of the meanings of any of the work here. Rather, what I want to do is talk about something more personal. When I think about the people who inspired me, the Firesign Theater is at the very top of the list. It was through them that I learned about Spike Milligan, who was their inspiration, along with Peter Sellers, Harry Secombe, and the Goon Show. After the Firesign Theater I found out about Monty Python, who seemed to me at the time to be an English version of FST (I didn’t learn about the direct connection between Python and The Goons through Beyond the Fringe until later).

What struck me most about the Firesign Theater however, and what made them so different from anything else as far as recorded comedy or conventional radio programs was their absolute disregard for a narrator. In their first four albums only one sketch has an official narrator, or announcer: Nick Danger, and that’s because it’s a direct parody of old time radio shows. But even then, they really didn’t place much emphasis on the narrator’s importance because both Peter Bergman and David Ossman acted as the announcer at certain points. The rest of the sketches on those first four albums only use an announcer if it’s part of the scene, such as when one of the protagonists is spending time watching TV shows. I had never heard any audio production before, record or radio show, that didn’t have some kind of an announcer or narrator… even the Goon Show. For me, the Firesign Theater was the first time I understood that narrators are not necessary; that if a scene is set correctly and the characters are strong and real, then no introductions or explanations are needed.

These albums cohesively demonstrated to me the absolute power of audio production and the true meaning of the theater of the mind. These were the first albums that I wanted to listen to with headphones, because it made the story so much more intimate, and it really drove the entire experience of how the voices of the characters blended with the sound effects to create an entire universe.

My favorite of all has always been Dwarf, the most complex and yet the simplest of all their work. Simple because it’s a very simple plot line: an elderly man, a former B-list Hollywood star, spends a night alone watching his entire life flash before his eyes on television because a number of local television stations (this was way before cable TV) are playing various movies and shows that he had been a part of in his lifetime.

Okay, that’s the simple part. The complexity lies in everything about the album, from the way it starts, with sounds of chairs scraping as people enter a room (a nursing home perhaps?) and then a janitor coming in to turn on the TV set, to a poorly done evangelical television show, to our protagonist’s entrance when he wakes up in the middle of the show and starts flipping the channels on the TV. He switches to a news program with the news announcer reading headlines that sound like they could have come from Fox News: “Big light in sky out east. Sonic boom scares minority groups in sector E. And there’s hamburger all over the highway in Mystic, Connecticut. Good morning, those are the headlines, now for the rumors behind the news.” Eventually, while ordering a pizza (with a strange flashback to Nick Danger) we learn the protagonist’s name is George Leroy Tirebiter. After he gets something to eat he continues channel surfing (this was before that term was coined as well) and comes across a game show where he is the contestant, watches a political ad that he’d made at some point years earlier, and then starts watching a movie he made as a teenager called “High School Madness”. Eventually he starts channel switching again and finds another movie, a war picture, from later in his life called “Parallel Hell”. He switches back and forth between the two movies until the characters blend together and get mixed up into the endings, along with more channel switching and craziness. Finally he is interrupted with a wakeup call from his answering service (this was before answering machines too), and he tells the woman “I’ve been up all night watching myself on the television.” Her reaction is dubious at best.

All of this is done without any announcer or narrator to give you a clue as to the nature of the journey, or pauses to allow for laughter so you can catch up. And it was a journey, which was obviously only suited for audio – no way in hell could you pull off something like this as a television show or in movies. That’s why I listened to it with headphones… so that I could fully concentrate on the amazing adventure being played out in my mind. This is an album that doesn’t give away its secrets easily. You need to listen to it multiple times to get everything, and not just because you’re laughing so hard at some of the lines that you miss out on the next developments. Even Stan Freberg, as much as I enjoyed and loved his work, never went out on an intellectual limb like this; even Spike Milligan never demanded so much from the listener like these guys. Dwarf was and is to comedy records what Sgt. Pepper was and is to music records… beyond revolutionary.

Now for those of you who might be thinking that this sounds like nonsense and it’s impossible to create audio like this and expect anyone to ‘get it’, let me tell you that Dwarf was a platinum album. They sold over a million copies, and that was back when a million was really a million and not just a fake title for a Facebook group. You see the Firesign Theater understood the truth about the audience, which was the same bit of truth that I was taught when I was at the Second City training center back in the mid-1980s: Your audience is always smarter than you are… and the more you insist on spoon feeding them your ideas, the more they will ignore you. If there is one rule I wish could be made into absolute law for radio, and all of the media, it’s that one.

Yes, you should listen to Dwarf, and all of the first four albums, as well as some of their later works. For those dim bulbs who say, “It’s too dated”, so what? Hemmingway is dated too, and yet I don’t see a lack of interest in his works. He’s still required reading in writing classes, and so too should the Firesign Theater be required listening in radio. Much of what constitutes today’s sketch comedy owes something to the Firesign Theater, even Saturday Night Live. The people who created the National Lampoon Radio Hour (from where some of the original SNL cast and writers came together, including Lorne Michaels) were inspired by the Firesign Theater.

Whenever I find myself stuck in a rut for creativity I try to think back to my inspiration and figure out how to stop over explaining, over talking, and over simplifying. From them I learned the genius of editing down to the most imaginative prose without fearing the message becoming lost in a wave of creative intensity. People always respond positively when they are presented with something brilliant instead of another trite piece of mundane mediocrity. You may not always be able to deliver brilliance every time, I certainly don’t, but if you have it as your goal, you at least will be less likely to commit the mortal sin of entertainers: boring your audience.

♦