by Steve Cunningham

It’s been awhile since we discussed backup strategies in this column, and hopefully most readers have adopted a strategy and stuck to it. I say “hopefully” because where mechanical hard drive reliability is concerned, things haven’t changed much in the past 24 months. In fact, there is quantitative evidence that says the situation has worsened, particularly with large hard drives.

Despite their high cost per gigabyte, much hope has been placed on SSD (solid state device) drives as a more reliable -- and faster -- alternative to spinning platters. But the available information shows this hope may be misplaced. A French site recently acquired proprietary data from a large French computer retailer on hard drive and SSD returns. While not a scientific survey, it was interesting in that it showed roughly the same failure rate for SSDs as it did for one-terabyte hard drives. More troubling was the fact that recent two-terabyte hard drives were shown to be still less reliable than either smaller HDs or SSDs, with one Western Digital model registering nearly 10% of units sold returned to the dealer as defective. Two terabytes is a lot of data to lose at one time; who in their right mind would entrust all that to a device with a one-in-ten chance of losing it?

This lack of reliability weighs heavily on RAP’s readership, but is not exclusive to them. Given the enormous amount of digital data that consumers generate today with cameras in their phones, books and magazines in their tablets, and music on their mp3 players, the total amount of at-risk data becomes staggering.

What is clear from all this is that a comprehensive, multi-copy backup strategy remains vital for production types, as well as consumers in general. Many of us have used FTP servers to get deliverables to our clients, but an FTP server still relies on a hard drive, or perhaps a RAID, so the redundancy is not there. Besides, today that server is no longer cost-effective; just try pricing out a commercial FTP service. But if physical storage is not safe enough on its own, then what is?

For many users, the answer has been to store data backups “in the cloud” using dedicated online backup services, backup automation software that writes to the cloud, or online “collaborative” services that allow users to backup and/or share files in the cloud. Please see the sidebar for a description of what it means for data to be “in the cloud.” We’ll wait right here until you come back.

FROM BOOKS TO BYTES

The story of cloud computing, a term borrowed from telephony, starts with the world’s largest purveyor of books. The granddaddy of cloud computing and cloud storage is Amazon.com. After the dot-com bubble, network infrastructure became less expensive, so Amazon modernized its data centers and increased its capacities. Afterward the company discovered it was using as little as 10% of its network capacity at any one time, just to leave room for occasional spikes, so it decided put the excess to use.

In 2006 they launched a service called Amazon S3, or Simple Storage Service, as part of their newly-formed Amazon Web Services division. Amazon reasoned that the vast infrastructure it developed to help it sell books and CDs online could be sold to software developers as cheap disk storage, starting at less than a dime per gigabyte per month, with additional charges for bandwidth used to send and retrieve data. Shortly thereafter other companies sprang up to re-sell Amazon’s storage product. Among these are DropBox, which synchronizes the contents of a single folder on your computer with a copy of that folder on DropBox <www.dropbox.com>, and allows you to share that folder with others. The DIY blogging site tumblr <www.tumblr.com>, popular with music groups, is also powered by Amazon S3. Heck, Netflix distributes their streaming and downloadable media from S3. And now there is a new, S3-powered, backup and collaboration service designed especially for audio production professionals called Media Gobbler <www.gobbler.com>, which is currently in beta (more about Gobbler below).

Amazon’s S3 product is available today to any Amazon customer with an account and a credit card. The interface to S3 is far from pretty, but it works well enough; create a “bucket” (the S3 equivalent of a volume or partition), make some folders, and put your files into those. Given the price for storage, the interface is a minor issue. I pay about $10 a month for about 120 GB of backup files that are available 24/7, and I could reduce that somewhat by moving some files to Reduced Redundancy Storage. RRS is $0.093 per GB/mo., as opposed to regular redundancy at $0.125 per GB/mo. The difference in redundancy is negligible -- losing one file out of 10,000 in 100 years vs. the same in 10,000,000 years. I can live with that.

If you find the S3 interface troubling or hate the manual-upload aspects of it, there are solutions. Bucket Explorer <www.bucketexplorer.com> puts a friendlier face on S3 on Windows, Mac, and Linux computers for USD $79.99; I bought my copy for much less during an online sale. On the other hand, if you only want backup and you want it automated, try Arq for the Mac <www.haystacksoftware.com/arq> for USD $29.00. For the PC try Cloudberry’s S3 Explorer (free) or their S3 Explorer Pro (USD $39.99, includes file compression and encryption on the desktop), both of which are at <www.cloudberrylab.com>. Incidentally, the Cloudberry products also work on Windows Azure cloud, the Rackspace Cloud and others, which is not the case for Arq or Bucket Explorer.

DO IT YOURSELF... NOT...

Other companies take a proprietary approach, building their own data centers and writing their own interface software. Dedicated backup services like Carbonite <www.carbonite.com> and CrashPlan <www.crashplan.com> use their own server farms. They come with software applications which run on a computer in the background, performing anything from a full-drive backup to simply backing up selected folders. Some come with restrictions (e.g., Carbonite won’t back up external drives), some charge a flat fee per month for unlimited data, and some have caps on storage or the number of computers they’ll back up for the monthly fee. But what they will all do is automate the backup process, requiring virtually no thought from you.

The king of collaborative services has to be DropBox <www.dropbox.com>. Founded in 2007, the company spurned a nine-figure buyout offer from Apple in 2009. It is estimated to have 50 million users, 96% of whom are using the free two gigabyte account to backup and share, well, up to 2 GB of their stuff. It’s free (at that level; 50 GB is $100 per year and 100 GB is $200 per year), and it works very well. However, it is not completely secure (see About Security and Privacy below), and it’s pricey for the paid levels. On the other hand, a similar service known a Wuala <www.wuala.com>, a division of hard drive integrator LaCie, is secure, as they don’t have the encryption keys, and is about half the price of DropBox for the same space.

The highly underrated Box service <www.box.com> went directly after businesses that used to use FTP and appears to have won big time. For production houses that want to replace FTP, Box appears to hit the sweet spot: for $15 per user per month, which is a bit pricey, you get 1,000 GB. That’s right, they give you an entire terabyte of storage, more than enough to back up a gaggle of client projects. The one drawback is that there’s a two gigabyte file size limit, which may prove problematic for some who do long-form work. But they have a 14-day trial, of which I intend to take advantage.

Then there is Microsoft’s SkyDrive <skydrive.live.com/>, which is part of the company’s Windows Live service. It is somewhere between a backup service (albeit a manual one) and a collaborative, file sharing system ala DropBox. The most interesting thing about SkyDrive is that it promises to be an integral part of the upcoming Windows 8 release.

Oh, and just to muddy the waters a bit further, a new offering from Google called Google Drive should show up as part of the Google Docs suite, sometime in the next few months. I’m just sayin’...

COMING SOON: GOBBLER

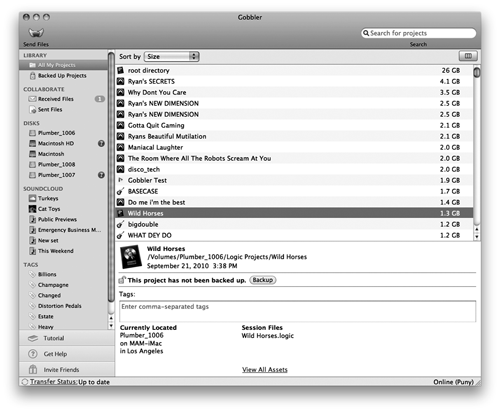

Last but not least, and this one could only be developed in LA: Media Gobbler <www.gobbler.com>, or Gobbler for short, is an S3-powered backup and collaboration tool with a difference. It knows how to backup, store, and retrieve projects created on Pro Tools, Audition, Reaper, GarageBand, and more than a dozen other recording apps, and dozens of other apps as well. Most audio project folders contain audio files, a session or project file, plus settings for fades, plug-ins, and who knows what else; all these items must be stored together and retrieved together, or the audio project won’t play let alone open.

So the folks at Gobbler built a database into the Gobbler application, which runs on your computer and presents the interface to all your projects, online, offline or on external drives. This database keeps track of all the files and folders that together make up the audio project, and makes sure they’re organized correctly for cloud storage and retrieval. Moreover, the database allows Gobbler to actually track different versions of the same project, which appears to mean that one could roll back to a previous version by retrieving it from the cloud.

Pricing plans begin at USD $8 per month for 25 GB and extend to USD $60 per month for 500 GB. There’s also a one terabyte and up plan whose price is shown as “let’s talk.” Gobbler is currently in beta for the Macintosh, but is “coming along nicely” on the Windows platform. It bears serious watching.

A WORD ABOUT SECURITY AND PRIVACY

Most of these backup scenarios, whether they’re proprietary or S3-powered, advertise that they store your data in an encrypted format for safety; however, there are a couple of small caveats. First, if some branch of law enforcement wants to see what’s on your DropBox or S3 volumes, a subpoena will open the castle doors with or without encryption. Even if they do store your data in an encrypted form, chances are some high-up employee or the company’s CEO has access and will comply with a properly-written search warrant or legal demand and will give up your stuff (and likely, you).

So if there’s some file or folder you aren’t comfortable enough to share with your Mom, then you might want to invest in some standalone encryption software. Encrypt the data before you upload it, so a hacker (or gendarme) cannot get into your data on the cloud.

This is particularly true with DropBox, who last year had to change their Terms and Conditions document. It used to say that no one at the company could get into your encrypted files, when it turns out that they do the encryption after the file arrives on their server, and do in fact have all the encryption keys. ‘Nuff said.

SIDEBAR: WHAT IS CLOUD STORAGE?

No, your data is not floating up in the sky, somewhere between the troposphere and the stratosphere. In reality, it refers to storing data on an off-site computer storage system, which is usually owned by a third party. In simple terms, you store your data on a remote server via the Internet instead of storing it on your hard drive or CD. Cloud storage offers some advantages over conventional data storage. For example, storing data on a cloud storage system gives you access to it from any location via a web browser and the Internet. So not only can you get at it from any computer with an Internet connection, but others to whom you've granted access can also retrieve your files. This arrangement allows you to not only back up your data, but also to share it with friends, colleagues, and collaborators.

In the most basic set up, a cloud storage system can consist of only a single data server linked to the Internet. In this case, a client (that would be you and your computer), who has subscribed to this cloud storage service, transmits file copies to the data server for storing. To retrieve those stored file copies, the client computer again connects to the data server via a Web-based interface. When requested, the server sends the files back to the client, or enables the client to work with the files online. The entities that provide the cloud storage systems are referred to as data centers.

In the real world, cloud storage services rely on many data servers in multiple data centers located around the world. Since computers can break down at any time, it is vital to replicate the information by storing it on different machines. This technique is referred to as redundancy, and it at the core of a cloud storage system. Without redun-dancy the cloud storage provider cannot guarantee 24/7 access to the stored information, much less a high rate of data retention (as in "don't lose my stuff!"). Furthermore, most cloud storage services store the same data on servers with features like redundant power supplies and redundant hard drives (RAIDs), and cluster these servers in multiple geographic locations to guard against power or network outages. In other words, your stuff is safer because multiple copies are stored on multiple servers that are scattered all over the place.

Cloud storage services are usually a part of a provider's overall cloud computing services. Cloud computing takes the concept of the cloud one step further by encompassing data processing as well as storage. The most obvi-ous example of cloud computing is Google Docs, which essentially gives you all the features of Microsoft Office via the Internet, including the ability to store and retrieve the documents you create with Google's word processor and spreadsheet software, running on their servers.

So your data is not "up there" somewhere. It could very well be in Brazil, Ireland, and New Jersey all at the same time.

♦