By Dave Foxx

By Dave Foxx

Starting with this issue of Radio And Production, I’d like to take a slightly different approach to this column, one that I think will be a lot more helpful, especially to up-and-coming young producers. All along, since I started writing a few years ago, I’ve gotten emails with specific questions that I’ve answered in this space from time to time. The rest of these columns dealt with issues I perceived as important to the business of radio production. I’m thinking that perhaps it’s time to let you ask me the burning questions and let me give the burning answers all the time. Frankly, what I think is important is likely not quite as important to you as what you really need to know, and I really want to make this column as pertinent to your everyday life as possible. And hey, if the quality of the questions does deteriorate, we can always switch back. So…if you’re just not sure how to do something, or just want a better explanation of some aspect of production, please send me an email. I will make it a point to answer your email directly, and then pick one or two questions for the next column. If you’re feeling shy because you think yours might be a dumb question, I’ll even keep your name and station out of the column.

I’m going to kick things off with a “How To” question from a producer from South America named Gillmor, who had heard or read something about what I call “permanent flange.” It’s a tool that I use to make the main voice in any promo sound truly PHAT. I’ve described it before in this column, but this time, I’ll break it completely down so you know how it works and why. That way, you’ll be able to experiment a bit to find a sound that really works well with the voice you’re producing, whether it’s yours or somebody else’s voice. What, Dave? You mean it doesn’t work the same on every voice? Nope. I think you’ll understand why when you understand how it works.

Let me begin with a short story from back in my “production only” days, before I was using my own voice. At the time, Z100 was looking for a new “signature” voice as our previous guy had always seemed really dark in his read, and management wanted to lighten the mood. We tried a guy named Charles Lamb for a while at about the same time as I was starting to play with flange. I loved how it added a new width to the track and made it sound larger than life. I would simply drop a flange plug-in on the track and dial back the “wetness” and voila! It sounded big and fat without really trying. But management didn’t care much for it, complaining that it gave a “swishy” sound to the track and made it seem like something out of a haunted house soundtrack. It’s a really cool effect, but it just wasn’t appropriate for what we were doing.

One day while doing a commercial read in Manhattan for an agency, I got into a conversation with the audio engineer, whom I had known for several years. When I told Doug how much I loved the bigness of flange, but that management didn’t like it swirling around, he said, “Freeze it.” When I looked at him as though he’d said, “Cheese it,” he explained how flange works. I had no idea.

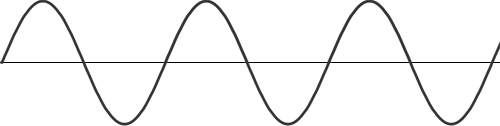

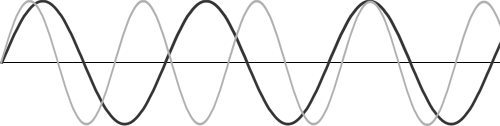

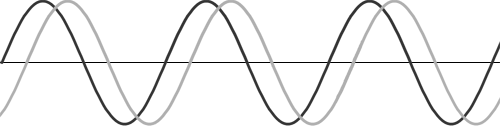

If you take two sine waves and sync them up perfectly, they look and sound like there’s only one. Each peak and trough match exactly. If you adjust the frequency (distance between peaks) just slightly on one of the waves, they are no longer in phase and you start hearing a rhythm as the waves first coincide and then drift apart. (That’s the swirl or swish sound the PD didn’t like.) Over time, the waves will sync up again, only to drift apart again. Each time they do this, the waves cancel each other when the peaks of one match the troughs of the other. So, the sound “narrows” then “widens” back and forth in a rhythm.

So, what happens if you keep the frequency the same on both tracks, BUT delay one just ever so slightly? The tracks are then “out-of-phase,” without the constant relative pitch change. They will sound either narrower or wider, depending on how much the one track is delayed. If the peaks of one match the troughs of the other, it is completely out of phase and the sound will basically cancel out, just as if you swapped the ring and tip of one of the signals. (I wrote a whole column once about how to “cancel” the vocal from a piece of music, using this very principle.) If it’s somewhere in between, you’ll get the fat sound I love so much, without the swishy, swirly sound.

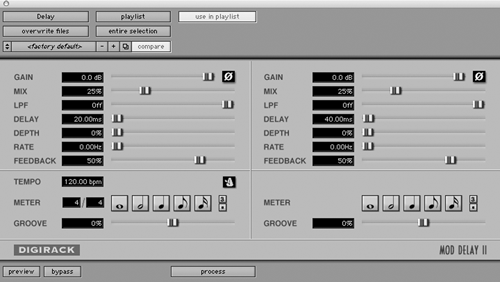

Previously, I explained how to do this manually, in the hope that the principles involved would become self-evident, but that probably just muddied the water enough to confuse everyone. Besides, I now use a much simpler method. Somewhere in your bag of tricks, you should have a plug-in that you might have never used. It’s called delay. You need a pretty short one, so if you have a few to choose from, use the short delay plug-in. Oh, and make sure it’s a mono to stereo plug in.

I prefer to put the VO on a send and add the delay to the return, making it available to multiple tracks, but you can put it directly on the VO track if the plug-in has a Mix or Wetness setting. Start out pretty light, say about 5% because a little goes a LONG way. If you use the bussing method, you should set the return to a low setting. (Don’t do both.) Now, on the left channel, add 20 milliseconds delay. On the right, make it 40 milliseconds. Hit play. Adjust the wetness (or return gain) until it sounds reasonable. Remember, you’re adding spice to the VO, not making an epic Cecil B. DeMille biblical “Voice of God” setting. If you go on the air with a setting that’s too strong, I guarantee your PD will hotline you, asking what the heck you’re smoking. Subtle works really well.

Once you’ve gotten this far, you can then find the ideal setting for the voice you’re using. 20ms and 40ms works really well on my voice, but I have a fairly resonant, low/middle range voice, so it doesn’t need much. If the voice is a little more bass or tenor, try increasing and then decreasing the delays. However, to work properly, one always must be a multiple of the other. I’m not even sure why that’s true – it’s just something I’ve observed. 15ms over 30ms and 25ms over 50ms are good examples.

For my track on this month’s CD, I demonstrate everything I’ve talked about here and follow it with one of our Z100 Jingle Ball promos using my favorite “permanent (not moving) flange” setting. You’ll notice, I do NOT use it on the artists VO tracks and I don’t use it on the hi-pass filter tracks. It’s all the “texture” on the overall track that I keep insisting makes the promo much more interesting to listen to, regardless of the content.

So, do you have a question for me? Ask anything you want. Well… let’s keep it on topic. I’m not sure how I would do answering a question about quantum mechanics, or even about gear you can find at Radio Shack™.

Feel free to email me at

♦