By Dave Foxx

By Dave Foxx

I’m not exactly sure why the timing works out this way, whether it’s an influx of new producers or, more likely, we all develop a forgetfulness in the late summer/early Fall, but I always seem to get a huge stack of requests to talk about EQ and compression in this space, right about this time of year. Considering that these two intertwined topics are so fundamental to what we do, I figure that a quick refresher is always in order. So buckle down troops, it’s primer time. Skip reading this month’s column if you’re a seasoned pro, or not, if you want to really fine-tune your skills.

Too often we tell new young producers to “just fiddle with it until it sounds right.” While this certainly gets them out of your hair for a bit, it hardly addresses the subject. While it is good for them to explore the possibilities, it’s too much like telling a medical intern to go into the operating room and dig around until he or she finds the pancreas. While the intern will learn a lot about anatomy first hand, the patient will likely suffer and possibly expire. The promo or commercial could easily die on the operating table if you’re not sure what you’re doing.

So, let’s give you the building blocks you need to understand EQ first, starting with frequency. A sound wave is a disturbance in the air, introduced by a vibrating object. The vibrating object could be the vocal-chords of a person, the vibrating string of a guitar, or the vibrating diaphragm of a radio speaker. Particles of air vibrate in a back and forth motion at a given frequency. The frequency of a sound wave is how often the particles of air vibrate when it passes. The frequency of sound is measured as the number of complete back-and-forth vibrations, or periods, of a particle of air per second. One complete vibration in one second is one cycle, or as physicists call it, one hertz (Hz), named so after a 19th century German named Heinrich Hertz who was the first to satisfactorily demonstrate the existence of electromagnetic waves.

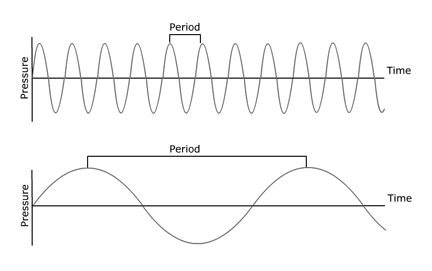

In the illustration below, the period is the distance between peaks or complete vibrations. The horizontal measure is time. For argument’s sake, let’s say the time shown is one second. Given that, the top graphic has a frequency of just a little more than 10Hz. The lower graphic is about 2.5Hz.

Putting this into context, the A above middle C on a piano is nearly always tuned to 440Hz. Check the tuning forks that piano tuners use and you will see the number 440 etched into them. The lowest note on most pianos is a C note, which vibrates at 33Hz, while the highest B note vibrates at 7902Hz. The range of the human singing voice is approximately 82Hz to 2093Hz. The human speaking voice has an even narrower range, which will become important knowledge down the road. Oh, and just for the record, the human ear is generally able to detect the frequencies between 20Hz and 20,000Hz (20kHz.) Anything below 20Hz is called infrasound, only known to be used by elephants over long distances and anything over 20kHz is ultrasound and is pretty much relegated to use by doctors, dogs and bats.

By far, the simplest way to learn how to work with EQ is to use a graphic equalizer. It can be a rack-mounted piece of gear (or plug-in) with a whole row of 10 to 32 little slide pots mounted side-by-side. Beneath each will be a frequency, arranged from lowest to highest, left to right, just like a piano. Each pot is capable of adding or subtracting up to 12db of gain for the frequency it’s assigned to. If you were to push all the pots on the left side down, the bass frequencies would all disappear. Conversely, if you pushed them all up, you’d get MEGA bass. So, basically, EQ is a really fancy Bass/Treble control, one that gives you some incredible control.

I recently produced a Jonas Brothers radio special celebrating the release of their CD A Little Bit Longer that was distributed by Premiere Radio Networks. The Jonas Brothers were in a nightclub venue in mid-town, while I was in my studio in lower Manhattan, getting a feed of their PA mix. Public Address systems are notoriously bad when it comes to frequency response, mainly to protect against feedback, and this one was no exception. Pretty much anything above 4kHz was severely rolled off. The first treatment I put on the track was EQ, with a push of everything above 4kHz. Remember that their voice ranges were well below 4kHz, so why would I need to push the highs? One more little addendum to the EQ formula is the science of harmonics, or reactive sound. When any object is hit with sound, it vibrates, first with the same frequency as the sound, but then it vibrates at higher frequencies as well, although with less volume. When those harmonics are removed from the sound in a room, it starts sounding dull, almost like you’re listening through a wall. By pushing the high end up artificially, I gave it a more “natural” sound.

When the physicists of the Bell labs were designing modern telephones, they determined that to understand spoken words, people only needed the frequencies between 400Hz and 3kHz. Using this knowledge, they designed the system to NOT pass frequencies outside those numbers to help them simplify design and ultimately expense. Having this information comes in very handy when you want to simulate a voice on a phone. Simply drop any frequency below 400Hz and above 3kHz and it will sound JUST like a phone conversation, without the usual attendant noise.

Want to make your VO sound like it’s on AM radio while broadcasting on FM? It’s the rare AM transmitter that can produce frequencies below 80Hz and above 5kHz. Knowing that, you can now emulate the AM broadcast sound.

So, you can use EQ to fix a problem and you can use it to create a “sound.” You can even use it to help your mixing. If you drop out all frequencies below 400Hz on your VO in a music intensive spot or promo, it will allow you to let the music ride much higher. Most music is produced with a heavy emphasis on the lower frequencies. By allowing the voice to “get out of the way” below 400Hz, the music can stay louder without fighting for dominance over the VO. True, the VO will seem a bit shrill to your ears at first, especially when you listen to it solo, but in the mix, it will sound perfectly fine. Presumably, you’re not going to be using a vocal from the music when your VO is talking anyway, so it sounds like your VO actually belongs in the song and, in fact, becomes the lyric track for the song.

I have one caution on EQ. Don’t PUSH any frequency too much. If it’s a fairly narrow frequency you are dealing with, you can push it some, but if it’s even a little wide, try de-emphasizing the other frequencies first. By pushing too wide a band, you run a strong risk of over modulating the signal and that never sounds good. A good rule of thumb is, a little EQ generally goes a long way. When you make it extreme, you’re going to create an effect that’s not always what you want. Yes, happy accidents do happen, but not nearly as often as total train wrecks.

Well… looking over what I’ve written, I’ve realized that the rest of this column is going to have to wait until next time. Unfortunately, or fortunately, depending on your point of view, in the next issue I’ll be writing about the Produce Dave Foxx pieces appearing on this month’s CD, so I’ll have to finish this up in the November issue of RAP Magazine. But this should get your juices flowing on EQ. NOW, go and fiddle with it until it sounds right.

♦