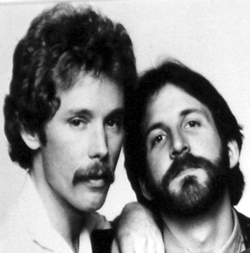

John Silliman Dodge, Bellevue, Washington

John Silliman Dodge is a busy man in radio land. In our last visit with John [February 1996 RAP Interview], we focused on his programming gig at KidStar radio, which blazed the way for Radio Disney. But there’s much more to Mr. Silliman Dodge. His 30-year career spans and integrates music, media, marketing, and management. He’s a graduate of Ohio University’s School of Telecommunications. He’s been a Julliard School of Music student, a recording artist for ATCO Records, and a Creative/Production Manager for KISS-FM in San Antonio as well as WROR and WBOS-FM in Boston. As Program Director, John pioneered the new school of commercial classical programming for WCRB-FM in Boston. He’s been a producer with Microsoft’s Digital TV team and a feature writer for several trade magazines. Today John actively consults the broadcasting industry in areas such as high performance announcer training, Web content, database and e-mail strategies, programming, marketing, high-impact audio production and creative copywriting. He’s also an announcer for Sirius Radio in New York. This month’s RAP Interview gets a much closer look at John as we catch up with his last ten years, which include the making of a CD of his own original songs. We’ve included one of those tracks on this month’s RAP CD.

JV: When we last checked in with you, you were Program Director at KidStar Radio in Seattle. Let’s pick it up from there. Tell us some of the highlights over the last ten years.

JV: When we last checked in with you, you were Program Director at KidStar Radio in Seattle. Let’s pick it up from there. Tell us some of the highlights over the last ten years.

John: I left a pretty secure position as Program Director of WCRB in Boston for the position of National Network PD of the KidStar Interactive Project. I did that because I took a calculated risk. I’ve always felt that if you don’t take big risks from time to time, you’re not going to jump very high. So I considered this carefully, and at that time, I thought they stood a really good chance of becoming akin to the next Nickelodeon, a kind of a multimedia network aimed at children, and so I took that chance. For three years it was a great run, but the company ran out of cash in the end. I don’t care how great your idea is, when you run out of cash, you run out of business. But I’m pretty proud that we were in eight, I think, of the top ten markets by the time we hit that wall, that we blazed the trail for Radio Disney, and so I look back on that time as well-spent and I’m proud of our accomplishments.

I got very interested in technology while I was working with KidStar. The Web, in 1994, was a pretty new frontier, and after the end of the KidStar project in ‘97, I went to work for Microsoft, because I knew how deeply media technology was going to impact the radio business and I knew how relatively unsophisticated we were back then about technology. So I kind of took a little Master’s Degree on the side.

I went to work for Microsoft for a year and several other companies in the dotcom space, and then after about four years I sort of brought that information back into the radio industry. I was able to do a lot of consulting with the Infinity chain, now CBS Radio in San Francisco, with their Web projects there.

Since 2001, I’ve have had my own shop, Silliman Dodge. While I was packing up my desk at the end of another dotcom failure we were involved with, I was thinking “it’s time to start working for myself.” And so I did that. Today, I have radio station clients around the country. I write for magazines, like Friday Morning Quarterback and Radio and Records, and sometimes Radio and Production. I do interactive workshops for announcer performance training and for Program Directors to help them maximize their relationships with announcers. No easy task, you know? I do that around the country at conventions and the like.

I’m also an announcer for Sirius Satellite Radio. I do two of their three classical channels. I’m the afternoon drive announcer, and I do that virtually from my home base in Seattle, while they’re in New York City. They came to me before they actually launched nationally, and I have been with them probably about five years now, since before they went public. And in the age of FTP, I can do that work from anywhere.

Also, since we’re in the 21st century here, I am the virtual Program Director of the Portland, Oregon classical station, KBPS, which is a station that’s doing wonderfully. It’s got a great staff and great management. I really appreciate that opportunity of them allowing me to work in this non-traditional manner.

JV: In our last visit, we never asked you how you got into radio. What’s the story on that?

John: Bob Rivers was the guy who got me into radio. Bob’s a famous morning personality and the author of all the “Twisted” tunes that we hear all the time. Bob was a Program Director in New Hampshire at a small rock station. I was a small rock star in New England, and our band broke up, as bands do. Bob calls me and says, “Hey, my morning guy just quit. If you’re knocking around, trying to figure out what your next move is, would you consider coming up here and doing the morning show?” And on a total whim I said, “Yes.” I took the road less traveled, as Carl Sandberg would say, and that’s made all the difference.

In addition to doing mornings, I became Bob’s Production Director, and then the Production Director at KISS in San Antonio, the legendary hard rocker down there. Then the Production Director for WROR in Boston, and then WBOS in Boston, where we debuted one of the first Triple A stations in the United States back in 1989.

But here’s the wonderful thing as it regards production: If you’d have told me when I started being a Production Director back in 1982 that in 2005 or 2006 we would be walking around with our laptop computers and little digital recording devices and little A-to-D converters and tiny little microphones, and we would be able to have the power of a zillion track multi-track studio in a nine-pound package that we could take with us on airplanes or anywhere, I would’ve said, “No way.” That is like too rosy a future. But it all came to be, and today that’s pretty much the way I travel. I do shows from Starbucks, from hotels, from train stations – you name it. Although sometimes I go through airport security, and they’re a little concerned about what all these electronic gadgets are all about.

JV: You have a good sense of trends and things on the horizon, especially considering how much you’re into the technology and your time at Microsoft and the dotcoms. What’s a little ways down the road that many people may not know is on the way?

John: Well, one of the things that I keep talking about in the Friday Morning Quarterback articles is what I’ll call the ‘democratization’ of music. Music is available from an increasingly wide array of sources. I mean, if you’re watching TV these days, you know that Verizon and all their associates, everybody’s making phones, and they’re going to make all the tunes available on their phones. So it’s one thing to see Apple’s iPod sell 20 million units or however many they sold, but believe you me, there are many more cell phones in the United States, and since we’re on the road toward becoming a one-person, one-cell phone nation, if the banking industry and the record industry and everybody can figure out how to make that one little gadget that everybody’s got in their pocket be the commercial gateway in and out of your life, they will.

And so, they’re going to. And if you have concerns about cell phone quality and cell phone minutes, believe me, all that’s going away. You’ll just plug your little headset into your cell phone, sounds like a million bucks, and they’ll do these macro-minute plans to enable it all to work. It’s the ‘razor and blades’ game — they’ll sell you the razor for nothing, and the blades in terms of music, or videos, or stock tips, or whatever. The blades will just keep on coming for the rest of your life. That’s one thing I see very, very clearly. FM terrestrial signals will become just one among dozens of ways that people have access to music.

I always say, now more than ever, the packaging and the presentation is important since your play list and Joe’s play list and Ralph’s play list is indefensible. I can copy that music and have it on my station in a couple of hours, but what I can’t copy is that unique sound that you have that is the composite of all of your production elements, all of the characteristics, the personalities that you have, your so-called ‘stationality,’ which is the personality of your radio station. That I can’t copy, and that, we now have to work on harder than we ever have before.

JV: You have several workshops that you offer and some are targeted to salespeople. What are some of the key things that you like to get across to the salespeople in your presentations with regards to getting the most from their production departments?

John: Salespeople need to get beyond order taking and into consulting. The majority of clients they deal with don’t know how radio operates. They literally don’t know how the medium works. We’re not great with the detail. That’s print stuff; that’s television stuff. What radio does best is create emotional impact. And so, rather than spend 60 seconds running down a data list — which I guarantee you, after the third point, your listener has gone blank on you — we need to use radio to create the feel of whatever the offer is. We need to do that rather than have a salesperson walk in and just take a selection of copy points out and hand those over to a Production Director who is expected to include the majority, if not all of those copy points, in some kind of list, and then run that list on a less-than-optimal frequency, only to have the salesperson go back to the client and hear him say, “I tried the station. It didn’t work.”

It takes a very smart and empathetic salesperson to be able to teach a client what that client needs, and then ask for his money. Some of our brash, 20-something kids don’t quite know how to manage that yet, and to their credit, maybe they’re not getting sales management teaching them how to be consultant salespeople in the streets today. I don’t know.

JV: Are you going out to radio stations in all market sizes with your workshops?

John: Yes. I work and have worked across all formats and all market sizes. I work in public radio and commercial radio, in community radio. The things I’m doing are kind of one step above those lines of differentiation. I work not only with salespeople, but I work with announcers. I do a half-day interactive announcer skills training program I call, “Inside the Announcer’s Studio.” I teach people how to be better communicators on the radio.

I work with Program Directors in a similar program that is a PD’s guide to getting the maximum performance from announcers. These workshop programs I peddle around the country and routinely get a really good response, although it’s one of those things that people acknowledge that they need but then can’t quite manage to put it into the budget. So if I needed to make a living on just workshops, I’d probably have a thin living but have a great time doing it.

JV: In your travels to markets of varying sizes, do you find differences in the sales departments in smaller markets versus those in larger markets with regards to how they approach advertising? Do smaller markets tend to have more salespeople bringing newspaper ads to their production people rather than acting as advertising consultants?

John: Believe it or not, it is not a matter of market size. It’s a matter of the experience and the perspective of the sales manager. If that person got to where he or she got and didn’t acquire these skills, then they’re just passing on what they know, and if all they know is to put pressure on their team and say, “Here’s your number. Go out there and get it. Don’t come back until you do,” then these people are just sort of hunter-gatherers in the field.

But if the sales manager knows how to maximize a relationship by using the consult and sell, and they teach those skills to their salespeople, then by and large, they’re going to be more effective, and I have noticed no difference in market size, station size, staff size. It all has to do with the expertise of the sales manager.

There’s a myth – the myth of the big time. When you’re starting off in your 20’s, and you’re at a small station in the boondocks, you have a tendency to think, “All of this bullshit, all of this stupid stuff, all of these people who don’t know what they’re doing... When I get to the top, I’m going to be done with all of this.” And then you get into the next size market, and you look around and unfortunately, you still have bullshit and some stupid people to deal with. And then you finally get to the top – you’re in New York City, L.A. – and you look around, and you go, “Uh-oh, there’s stupid people here, too.” So I’m afraid stupid people are going to follow you around for the rest of your career, and the best thing you can do is to sidestep them at every turn.

JV: Your “Managing Creativity” workshop is geared towards the PDs and among other things helps them manage and motivate the creative people in the building. What’s one thing you find that many PDs overlook about their in-house creative person, or one thing that you try to get across about getting the most out of their prod guy?

John: A lot of Program Directors haven’t figured out the mathematics of radio yet. They’ll have all of these promo concepts that they want to get across, and they’ll run to the Production Director and say, “We need a promo for A, B, C, D, and E.” Now, forget the fact that this Production Director in the 21st century probably has more than one station to produce – some of these guys, as many as five – and there’s that much work times five, plus the commercial work, so all of this workload goes up, but hands to do the work don’t go up commensurately.

But the Program Directors who get it understand that in order to create big impact, you run fewer promos more frequently. There’s a system well known in sales called, ‘optimal effective scheduling’ that shows you in a very clear and simple math model the proper number of times to run any message — whether it’s a promo or a commercial or whatever – any message on your radio station in order for three impressions to be reached by the average listener. That turns out to be the magic number: three times and the listener’s got it. And when you run the math on most stations, that equals a pretty high number for any one promo, higher than most PDs are able to stomach because they think, “No way am I running this thing like 45 times a week on my radio station.”

So they’ll ask their producer to make six different promos for six different things, and run each one of them nine times, which sounds like a lot, but when they do the math they find that they’re not even penetrating 15% into their core audience, and they’ve just wasted everybody’s time in the process. So if I were managing up, and that is the art of subtlety managing your own boss, I would make sure that the Production Director, 1) had enough time to do a good job – a really good job, meaning interesting, fresh perspective, not just recycling the same old lasers and blasters that we’ve heard since 1981 – a good job with each message, and then, 2) that the Program Director would schedule that message enough so that everybody in the audience could hear it at least three times.

JV: I’m so glad you bring that up. I’ve often wondered what that formula is and what that number is.

John: You take your cume and you divide it by your average quarter hour. Let’s say your cume is 100,000 and your average quarter hour audience is 10,000. That’s a factor of 10, which is the turnover ratio, or the number of times the station turns over or recycles its audience in a week. You multiply 10 by 3.29, which the cognitive researchers tell us is the number of times people need to hear a message in order for it to register. And that gives you the number of times you need to run a message in a given week.

JV: That’s so important, but how many times have we all heard PDs say, “That promo is old. It’s not fresh anymore. Cut a new one,” and in my mind, I’m thinking, “You know? I bet the audience is just starting to get it.” It’s the same thing with music. Jocks get sick of a song just about the time the audience decides it’s their favorite song.

John: Right. We have our heads so far up in Private Idaho sometimes that we forget how listeners use the radio station. I mean, the average time spent listening is a well-known number. The PD should make that number known to everybody in the radio station so that we understand that we’re inside, drinking this Kool-Aid 24/7, but the average guy on the street, what’s he with us? Two hours a day?

JV: You also have the “High Performance Writing” workshop geared towards writers and producers. Tell us a little about that, and what our readers could expect to gain from this workshop if they were to take it.

John: Well, I have always known that when you strip away all of the sound effects and all of the sonic tricks, you are left with the most fundamental instrument we have, and that’s the single human voice. And as they say in the theatre business, “It ain’t on the page, it ain’t on the stage.” So writing is the single most important skill in radio, and not only is it undervalued, it’s way underdeveloped.

I don’t know any Production Directors off the top of my head who go in with a writing background. It’s something they pick up along the way, and that’s good, but what I try to do with this course is break that down. It’s very much a writing fundamentals workshop. I’ve been a writer all my life, and what I did was go back and digest all of the great works about writing and distill this into one really tight little package.

There’s a handful of books on the subject that I recommend. Rather than give you a bibliography, people who are interested in that short list of great books can drop me a line [at

JV: You mentioned that you’re voice-tracking your Sirius gig from home. What’s in the studio?

John: I use Adobe Audition with a rapid write hard drive in my Dell Inspiron 6100 laptop. For a voice processor, I’ve got my trusty old Symetrix 528E. And my microphone — a good, general, all-purpose mic — is an AKG C4000-B.

JV: Any thoughts on voice tracking versus the live jocks?

John: The trend toward voice tracking will only continue. Stations routinely now are voice tracking after 7 p.m. at night and all of the weekends. A lot of times, even the primary day part, 6 a.m. to 7 p.m. Monday through Friday has been voice tracked, although those announcers are still in the radio station doing other things.

So the shift from being live behind a microphone, knowing that when you open the mic, there’s 6 or 9 or 20 or 50 thousand people listening to you, and going in to a little booth where you crank these breaks out one after another after another, that shift is really radical for a lot of performers. And a lot of them, frankly, don’t quite make the transition from live performer into prerecorded performer.

It’s a difference, in my mind, between an actor on stage who has an auditorium filled with people who he can relate to and react to, and an actor in a movie, where there’s just a couple of people on the set, and the scenes have all been taken out of context and he has to switch it all on for three minutes, and then switch it all off again. So our announcers, and indeed our Production Directors need to become better actors. Actually, I think the producers have something to teach the announcers in this regard, because Production Directors have been going into the room and pulling up the juice and delivering un-live for years.

JV: Are you doing some commercial VO work as well?

John: I get the occasional VO job, but I don’t solicit it, and that’s what you really need to do if you’re going to be big in that arena. I just found that I am active in so many other areas that that’s one thing that I used to do all the time when I was a Production Director, but I just don’t do too much anymore.

JV: How do you manage your time? Are you finding yourself unable to do a lot of things because of the many duties that you have?

John: Well, vacations are one of the things that I’m unable to do. I have to be a very careful time manager. Every day, I have to take a look at the list of priorities of things that have to happen that day, and in the next three days. The trap here is that you get so busy with immediate deadlines that you stop thinking long-range, and it’s critically important to reserve some time to think strategically about what you do, about where your career is headed, what opportunities are ahead that you want to position yourself for, what people you need to meet to build your network.

I can’t tell you at my age now how important making friends in the industry all this time has been, because I’m still tight with people that I’ve been working with now for 25 years. I don’t burn bridges because you never know when you need to cross back over.

JV: You also have a CD of your own music. It’s interesting that you brought up earlier in the interview that you were a musician before you got into radio, and that’s something that you still have managed to keep alive. Even with everything else that you’re doing, you’ve cranked out a CD of original music. Tell us a little bit about this music venture.

JV: You also have a CD of your own music. It’s interesting that you brought up earlier in the interview that you were a musician before you got into radio, and that’s something that you still have managed to keep alive. Even with everything else that you’re doing, you’ve cranked out a CD of original music. Tell us a little bit about this music venture.

John: I’ve been playing guitar since I was about seven years old. I’ve always been a musician. I spent my 20’s writing songs, playing guitar, playing in bands, making records, touring around the country. I played opening acts for so many names that you know from the ‘70s and ‘80s. But then, at age 30, I got into radio and had a wonderful time since then doing that. That’s been almost 25 years, but I have always been a musician, and never stopped doing that.

I had a very unusual year in 2004. My best friend is a fellow who I’ve known the longest in my life. He was the bass player in my band when I was in my 20’s. Richard Gates is his name. He plays bass for Paula Cole, for Patty Larkin, for Suzanne Vega. Well in 2004 Richard was diagnosed with a potentially fatal heart disease, and there was a time that we though he might die. And I thought to myself, “I have never made a CD with just Richard,” acting in the dual roles – he’s a good record producer, as well as a great bass player, kind of like a McCartney-level base player. So I went to him and said, “Do you have enough energy to do this project?” And he said, “I would love to do this project with you.” I said, “I’ll come up with a budget, and you just pick the tunes, you pick the side musicians, you pick the studio, you do everything that a producer normally does, and I’ll bankroll the thing. We’ll use my songs. I’ll sing and play acoustic guitar.”

It’s one of those things, if you knew you were going to be dead in nine months, what would you do different? And so, I just did that thinking that I don’t want Richie to slip away without us having this experience together. We did this record. It’s the first one I’ve made since 1980. I’m really proud of it. Richard, as I said, produced and played bass.

About six weeks after we finished the record, Richard went into the hospital and received a heart transplant, and now, a couple of years later, he’s doing wonderfully. He’s newly married, and the outcome has just filled me with joy.

JV: Great story.

John: I’ve got a second story to tack on to that. What are the chances of a guy’s two best friends both needing organ transplants? I figure next to none. But the other case involved my friend, Paul Yeskel. Paul is the President of AIM Strategies, which is one of the biggest classic rock record promotion companies in the industry. Paul was diagnosed with a potentially fatal kidney disease, and he and I are talking about this at the Conclave Conference, which is held every summer up in Minneapolis. Paul’s starting to freak out about this because his blood chemistry is starting to go south on him, and the doctors are saying, “You either need a transplant, or you need to go into dialysis here very shortly.” I said, “Paul, what’s your blood type?” He said, “A positive.” I said, “That’s my blood type. I should just give you one of my kidneys.”

And to make a very long story very short for your readers, that’s exactly what I did, about 15 months ago now. We went into the Robert Wood Johnson Hospital at Rutgers University in New Jersey, and they took my left kidney out of me and they installed it into him, and so now between us, we’ve got only two. We call his “Billy the Kidney.” Every time we’re out together, people say, “Oh, how are you doing? How do you feel?” He’s doing fine; I have felt fine since a couple of months after the operation. It took me about a couple of months to recuperate. It’s a pretty intensive operation, but after a couple of months, you don’t even know that you’re only working with one kidney, because your body really only needs one. It’s the only place where God over designed the instrument.

All of these things happened all in one year. As I said, a big year – 2004. I came out with a record, my best friend got a heart transplant, I gave my kidney to my other best friend.

JV: Over the past ten years, as you’ve bounced around the country looking at the different radio stations and kind of getting a sense of the production departments, how have you seen radio production evolve, and do you have an idea of where it’s headed?

John: Well, certainly consolidation has meant that more stations are under the control of fewer people, and the reductions in cost meant that now one Production Director has multiple stations to take care of. And so we have to, as a result, learn how to work smarter, because there’s only so much time in the day, and we literally can’t work harder. Figuring out priorities and rearranging priorities on a daily basis is a key skill for a Production Director today.

The other thing I’ve noticed, and maybe this is just my perspective, but I’m getting more and more fond of reality. Every time I hear a promo that’s nothing but bangs and whizzes and funny voices and EQ and stuff like that, I don’t react to it in the same way that I used to. It’s almost like my imagination says, “Been there, done that too many times.” I am much more apt to react to the quality of a human voice and the character of the emotion expressed in that voice, and the words.

Now, I think we’ve come back full circle to the message. So if I had to say what’s the single most important skill a radio Production Director can have today? It isn’t a big sound effect library. It isn’t a great big bass voice. It’s can you write well, and can you emote what you write on the radio?