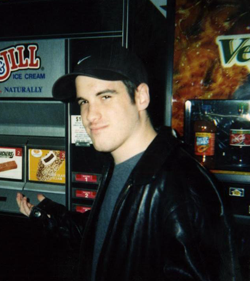

Christopher O'Brien, Creative Services Director, WMWX-FM, Philadelphia, PA

By Tom Richards

By Tom Richards

In a mere four years, Christopher O’Brien has leap-frogged into the elite group of radio’s most talented imaging icons, having plunked himself into the CSD chair at Infinity’s WYSP Philadelphia at the age of 20, segueing to XM Satellite Radio soon after, and presently perching at Greater Media’s AC, WMWX Philadelphia. He’s covered a wide breadth of styles along the way, currently paring down his sound for a less aggressive audience. Chris’ ideas, though, continue to explore new territory. RAP recently caught up with him in his Pro Tools-equipped studio, overlooking suburban Philly.

TR: Is it true that you started on a cassette machine?

Chris: Yes, a Tascam Porta 07. It had four tracks, which I really utilized to their fullest capacity. My grandfather got it for me when I was around 15 or 16 years old. We went to a recording store and I was looking at Harmonizers and stuff I just couldn’t afford. I had been mentored by David Jay who was the Creative Director for WIOQ, and he had done this neat stutter effect with a Harmonizer. I had always loved that effect and wanted a Harmonizer, but I had no idea they were like $3000 bucks. I also wanted a 4-track so I could actually start producing. At that time, I felt that’s what could make me be like a pro. So anyway, I had looked at this 4-track. I only had like about $100 bucks in my bank account, and it was like $350 or $400 bucks. I thought, well maybe in another four months I can have it. Well my grandfather who drove me there managed to buy it and sneak it into the trunk, and when we got back home, there it was. I was like wow! This is so cool. And it was at that point in my life that I became an instant recluse. I was in my bedroom almost all the time. I slept, went to school, then came home and played with my 4-track. That’s all I did.

I was able to do flanges by offsetting the left channel with the right channel with the little pitch control knob. If I was recording something, I would count, one, two, three, and I’d make this slight noise with my chair that was pretty squeaky, and that would be the trigger to hit pause on the 4-track so I would be up there tight with it. And then I would listen in cue along with the other track and adjust the pitch so it would go off just a bit and I would have flange.

But I still didn’t have a Harmonizer, so I had to figure out how to do stutters. I figured out that if you potted the main master track of the Tascam down all the way to the bottom and you hit pause and then unpaused it when I heard the click of the chair, for a second, and each time adjust the pitch up or down, you’d get that b-b-b-b-b-b-b [high pitch to low pitch] noise. And if I was really trying to be cool, I would do it live right in the Tascam. And I was able to use the panning on the mic track to get that left to right bounce. The only problem with that is that you had to be pretty exact.

TR: Sounds like you would do whatever it takes to create an effect.

Chris: Oh yeah. That’s like when I was trying to build a reverb box. I don’t know if your familiar with this, but there was a place down at the Jersey shore on Wildwood Boardwalk where they had these 99-cent echo mics. They were just a spring in these little plastic things, and when you were talking into them, it sounded like reverb. Well I wanted stereo reverb, so I bought two of these things. I had a little wooden box that I had since I was a little kid, and it became the box for the first half of my reverb unit. Then I got another box that wasn’t the same size and I glued them together, one for the left channel and one for the right. I took these two tweeters because I figured that reverb to my ears was a very high frequency thing, and I wanted to highly modulate the microphones with the tweeters. These tweeters would blast through those mics. And then I had telephone receivers that I got from my Grand mom who used to have these old phones you could unscrew, and they were real easy to hook up. And I had that going into a little Radio Shack mixer. I also had my microphone split. I actually cut it. And getting rid of the hum took me three weeks. I didn’t realize about grounding back then.

TR: All the engineers must have been tearing their hair out in their dreams.

Chris: Well it’s funny you should say that. When it was all said and done I had a very crude reverb box that I only used once, but I think it was the dedication of building it that led me to my first reverb box, which I still own today, which is an Alesis Microverb. I won’t say the engineer’s name because it could make him look bad in these corporate days, but I went in and showed him my reverb box, proud as could be, and he goes, “Oh my god, I can’t let you put audio through that.” So he comes back and hands me the Alesis reverb box and says, “Put it in your bag. Just promise you’ll never run audio through that other thing.”

TR: So you made that little Tascam 4-track do what it was not meant to do.

Chris: Yeah. I was bouncing tracks and all that stuff. I didn’t mix the way you were supposed too. I had no formal training in that art so I just assumed that you were supposed to set mix levels as you record it in, which made my mixing a lot easier. Since I was doing a lot of bouncing, it was already at the volume I needed it to be. And that’s actually how I got good at mixing without compression, because I had none. I had no idea what compression was. I knew that stations had that on their processing chain, but that’s about all I knew. I didn’t know what it did.

TR: How did you get your internship at WIOQ with David Jay?

Chris: I met David at a very early age. I forget how old I was at that point, but I called him a couple of years later said, “I want to do what you do.” He goes, “I’m not on the air. I’m not a DJ.” I’m like, “I don’t want to be a DJ. I want to do what you do. I want to produce like Mark Driscoll and create that magic, the colors that come out of your speakers, the anthems of the station.” And he was like, “Well, why don’t you come down and hang out one day.”

He’s at KBIG in LA right now, and I still talk to him twice a day. It’s been a great working relationship. It’s grown to the point now where I’m teaching him about Pro Tools. But I never got to watch him produce analog. I always watched him with the digital editor. I wish I could go back and somehow watch him during his analog days. I’ve heard it was like watching some kind of wizard at work.

TR: And then you got your first break at a small station on the Jersey shore, and then got yourself into WYSP in Philadelphia.

Chris: Well I made a pit stop at SoundByte, this production company. And that was really cool because that was my first Pro Tools experience. I’m not the type of person that reads manuals, and it took me a good three weeks to figure out how to group the tracks. I wouldn’t ask anyone. I had to learn it myself. The company was starting out when I got there, and I was able to grow with the company. It was like the University of Pro Tools in a sense. I got to spend all my free time crafting and learning how to use that workstation, and little did I know just how far that would take me. As you mentioned, my next stop was WYSP and they had Pro Tools, and then I went on to XM, which had Pro Tools, and here at MIX we have Pro Tools. So it’s really taken me through the major professional part of my career.

TR: You also know some Windows stuff as well, right?

Chris: Yes. I can do a killer beat mix on Cool Edit Pro if I need to. And I played around a little bit with Sonic foundry stuff like Vegas. But I guess I’m getting to be an old dog because Pro Tools is just more me, you know. For me, it’s not really a workstation as much as an extension of my will. It’s like a car you don’t want to get rid of. And they keep giving you cool upgrades. So I get a new muffler package and engine every couple of years.

TR: How do you approach Pro Tools that might be different than somebody else?

Chris: Well I think everybody approaches a workstation in his or her own specific way. It’s a very complex question because I approach the workstation for the type of format I’m doing. When I was doing rock production at WYSP, I approached the workstation as this juggernaut, this thing that would follow my will off a cliff, with blind and elicit devotion. Now, when I do Hot AC stuff here, it’s more an orchestra that I’m conducting. I guess it’s a lot like if you’re driving in the morning and you’re in a good mood, the car’s taking you to a place; but if you’re in a more aggressive or intense mood, you’re driving the car. And you know it’s funny, when I do intense stuff, I come off it feeling tired and not sure what I did. I didn’t know what I was producing. It would be four days before I’d say, that was an alright piece. Whereas when I’m doing stuff that’s more orchestrated and more from the heart and soul, I listen to it and instantaneously know that it’s a good piece.

TR: So it sounds like the stuff you’re doing now is less dense.

Chris: Yes. It’s more of “less is best.” I went through many different stages. When Tim Sabean at WYSP hired me, I had no idea what rock music was. My first project was to make a hook promo, and I picked all the wrong hooks. And he said to me, “Wow that’s great. It sounds like new music. You made Hendrix sound like a top 40 hit. I love it. Put it on the air.” I now tell people my start was WYSP because I had no idea what I was doing. I went there and for the first year wasn’t using any compression. You’d have this heavy duty Limp Biscuit song followed by my production that was going through the station’s chain, and it sounded like it had reverb on it just from the compression. And then I had to start competing with the compression on the station, with my own compression within Pro Tools.

TR: Then you had to make a voice cut through all that too.

Chris: Yes. But when you have Howard Parker, that’s not really a difficult task. And what I loved about Howard was he was the knife, the edge of my sword. He was the thing that just drove right through everybody else. It was great having him. From a voice guy perspective, that was probably the highlight of my career and probably will be because working with a guy that went on to his greatness is just amazing. Him and I are still very good friends.

TR: Your next stop was XM Satellite Radio in Washington, DC. Tell us about that.

Chris: I got a call from XM, and they were interested in my stuff. They had gotten an MP3 from one of their guys there whom I maybe did a voice audition for or something. It’s kind of foggy. At any rate I get a call from the guy; “Hey, you want to come down here?” I’m like, “Alright.”

TR: What was it like when you got there?

Chris: Very, very interesting because you had two fronts of people there. You have the people who were, I guess you can say, the seasoned veterans — Lee Abrams and others like that. But then you had another front of people, especially in the production department, because they didn’t hire many guys from major stations. They were apparently looking for people out of the box. But I think, and this is just my opinion, I think that one of the big problems and a lot of my differences of opinion with the XM management were that their idea of amazing radio was small market radio. They would hire people that came from small markets. I mean, hey, I came from a small market. Everybody does. But when you are in a small market, exposed to people who are learning and or people who aren’t happy to be in that market and don’t want to move on, there’s a level of professionalism and experience that is lacking there in a place where the stakes aren’t that high.

TR: What was the idea behind hiring small market people?

Chris: I’m not sure. I think there was a degree of this is the way we were going to do radio: anti-FM, which was the entire approach and was a good idea.

TR: As FM sprang from what was termed commercial AM radio, XM was perhaps trying to evolve out of the now commercial FM band.

Chris: Right. And so they had this very, “can’t sound like normal radio” approach. Which is fine. I love that. I also got very socially active when I got there, which was a new thing for me. Then 911 happened, which was like the day before we were supposed to launch. I would run across the street from the Pentagon and actually witness that whole tragedy. That really affected me personally, and for like three or four months after that, production wasn’t really that important. The air was let out of the sails. It was like, okay, what are we going to do now?

I did get some more Pro Tools experience there. A lot of the people that they hired knew nothing about Pro Tools, so they brought in Pro Tools pros to teach people. I got the benefit of that because I got to find out some stuff about Pro Tools I never knew about before. It’s amazing how many bad habits you form when you don’t read the manual. So yeah, I got to do some pretty out there stuff at XM, unfortunately a lot of it didn’t air.

TR: Why?

Chris: Well it seemed that if it sounded good in the realm of the major market sound, I guess that wasn’t what they were going for. They wanted it to be less polished and more kind of organic. They used voice talent within the building, so that was kind of foreign to me too.

TR: People who weren’t really voice pros.

Chris: No, and it was really hard to create art that way. I went from using a guy who went on to be the hottest movie trailer voice to using Joe Schmoe down the hall to read a promo. And I understood where they were coming from. If we want to sound different than normal radio then hey, let’s do it this way. But it was very hard for me to adjust to that because I was brought up differently, and had been to that point very successful in FM radio.

TR: You were a racehorse and suddenly they were making you trot.

Chris: Exactly. I made a lot of great friends down there, but for both of us, it was time to separate. I don’t regret going there, but I just think that their idea of amazing radio was my idea of small market radio, and that was just a difference of opinion.

TR: So that leads us to Gerry DeFrancesco. He called you up?

Chris: Yes. And he was like, “Hey I heard about you. A couple of people recommended you for this position. Let’s talk.” I listened to him, and at first I thought, Hot AC? I do rock. I was wondering if I was the best man for the job. So we kind of tabled the issue for a while, then he came back to it a couple of weeks later. I came up here and talked to him, and he was very positive and uplifting. I got that from him almost as a human being and not so much as a Program Director. So I talked to my agent, said this is where I want to go, and I started here two months ago.

TR: How it’s different there.

Chris: Oh, gees! Well we’re not a part of Clear Channel or Infinity. We’re Greater Media. I’ve got to tell you, the way this radio station operates is the way I’ve always dreamed a radio job should be. Gerry is taking great care of me. He lets me do my thing, is supportive, down right loving. It’s amazing. I’ve never worked with a Program Director who comes in and has the same energy level I do. We feed off one another, and it’s wonderful. Every now and then I’ll do something and he’ll have me pull it back just a hair, but never in a negative way. He’s always very supportive. And that’s all around the radio station here.

TR: So how is your production sounding now?

Chris: I think I’m doing some of the best stuff in my career right now. The stuff I did when I was at WYSP, which bled through to a lot of the stuff I did at XM, was very intense, balls to the wall. And it really got to the point that if I had done anymore it would have been distortion or static. It was really that intense. I’d be using something like 60 tracks sometimes. It would be crazy. I’d feel like I went through a war at the end of day. And now my stuff is very orchestrated. Like I said earlier, less is best.

I guess you can say I’m at peace with myself. There was a point where I was always trying to outdo the next hotshot imaging guy, and then I realized that if you’re able to do artistic cinematic radio and paint pictures with music, sound effects and voice, you become more of a composer than a producer. I just get so much more out of my job right now than any other radio station or any other place I’ve worked. I was talking to somebody the other day and they said, “This is the job you were meant to do from many years ago. You had to go through all that crap to get to this job.”

TR: So it’s the kinder, gentler Chris O’Brien.

Chris: I guess, yeah. The female friendly Chris O’Brien. And I’m sure people have done this, gone from Rock to Hot AC, but I’m not sure how many were able to do it at my age because most people my age are still wanting to do that aggressive stuff. And once you can do that you can always do that. It took me maybe two hours to do a promo at ‘YSP. I’ll spend six hours on a promo with less elements here. But you’ve got to spend time looking for the right music, looking for the right sound effect, the right voicing, the right script. Script and voice become so important. Coaching is the most fundamental thing right now in my production.

TR: Who are you using for voice and how do you coach him?

Chris: Earl Mann. He does NFL film stuff. And I’m not sure how many radio stations he does but I believe he’s newer at radio, and it’s really neat because he doesn’t suffer from some of the crutches that certain voice guys get into where it’s like, [harshly] “It’s a no nonsense weekend!” He’s more like, [softer] “It’s a no nonsense weekend here.” Much more friendly. I use his growl like I used to use a Harmonizer for effects. When I want to punch the listener just a little bit upside the head, I have him growl.

I also record him doing the same promos at least three times. For example, this past weekend we did this Bunny Bucks weekend and I wanted “bucks” to have more punch than “bunny,” so I had him read the entire promo aggressively, and then I had him read it friendly, and then goofy. And I took the “bucks” from the aggressive read and put it in there with the friendly read. So I was able to mix and match, and he works really well like that. I had that when I was working with Howard. He was very good at that. But he also worked in the next room, which was the coolest thing in the world.

And speaking of the next room, talking about the environment around here, I work right next door to my old competitor, Steve Lushbaugh. He is just so supportive and very cool. And at one time we were archenemies because he’s at ‘MMR and I was at ‘YSP. He’s just a great guy, and when I’m having brain dead days I’ll run into his studio and feed off of him, and he’ll feed of me hopefully. This environment is great. Everybody around me in this building is just awesome. I always loved my job even in the hard days, but I never enjoyed getting up in the morning and going to work more than I do now.

TR: Well with regards to your production style, it sounds like you’re not exactly searching for the next effect anymore but rather maybe using what you already have in better ways.

Chris: Well right now I’m back to not using any kind of compression on my final mixes. And I have the human user interface, which makes that real easy. I mix with the flying faders. As far as effects, I still search for them. When I was at ‘YSP, I only had what came with Pro Tools, no plug-ins, so I had to create a lot of my own effects. I did have two Harmonizers, which made it slightly easier than the old days with my 4-track, and I used a reel-to-reel machine too. That’s how I did things that you would use the Verify plug-in for with Pro Tools, which would slow things down and stuff.

But as far as plug-ins go, I like to know that if I want to do a certain type of effect I can; and I may not use it in every promo, but I want to know I can. We have Pitch Bender here and Focusrite EQ, which is my EQ of choice. I love that thing. It’s so warm and easy to use.

TR: What do you like in the way of a production library?

Chris: I’ve always made my own stuff. I’m in the process of making a library right now. I made one a couple years ago and never really did anything with it but just kind of passed it to my buddies. It was called Amplitude Ejaculations. But I’m working on one right now and it should be done soon, and when it is, people will know about it. But I don’t know want to tip anybody off yet.

TR: Any final thoughts for our readers?

Chris: Radio can be and still is fun. Terrestrial radio, as it’s called in the satellite world, is not all bad. There are guys that are still doing amazing, just incredible work. Consolidation has messed up FM radio a lot. A lot of stations like Q102 here in Philly have a lot of stuff on the air from other markets. And to me that’s just sad. At least the major market stations should have their own Creative or Imaging Director. And it’s sad that there’s nobody in the minors really coming up anymore. There are no new star players growing, at least that I know of, and that’s because they’re not allowed to blossom and take chances and make mistakes and experiment. I have that freedom.

Be yourself. And if you’re working for a station that doesn’t allow you creative freedom, do it their way until 5:00; but then stay until 10:30 at night and do it your way and make yourself a demo tape and send it out and get yourself a major market job because the majors are starting to get to the point where they need fresh blood. It’s a constant re-cycling of the same people, and it’s going to come to a point where those sounds start to dull, and all of a sudden no one's going to be able to cut the meat anymore. So if you’re out there, be you! Have fun! Enjoy radio! You can get paid a lot of money to have fun, and that’s the most beautiful part about this industry. I have a positive outlook on it. I’m in Philadelphia, a major market, doing radio the way I want to do it, having pretty much creative freedom. So it still does exist, and sometimes you have to go through some crap to get to that point. But once you do, it’s worth it. Trust me.

♦