By Dave Foxx

By Dave Foxx

My dear dudes and dudettes, the one question I get more than any other is, “How do you do those beatmix promos?” Well, it’s time to spill. First, you need a time compression/expansion algorhythm plug-in.) Second, you need to know how to count, and you need to know how to find the downbeat. If you don’t know, find out. It’s really not something I can explain on these pages. (I’m assuming you know how to count… it’s the other thing.) Check with a music teacher, or ask Madonna next time she drops in. I’ve taken the liberty of dropping the finished version of this promo, along with a couple of mixouts on the CD, which you are free to steal, use and abuse.

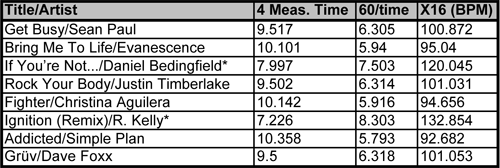

First, getting all the songs to ‘match:’ Using the downbeat as your starting point, count (to the music) to four – four times. The ones will ALWAYS fall on the downbeat for each measure. Mark the time precisely. Using “Get Busy” by Sean Paul, the time for those 4 measures should be 9.517 seconds. (You lost yet?) Do the same for each of the songs you want to use. If you look at the chart, you will see that the times you have are NOT the BPM. The times are used to determine the BPM. Divide 60 by your time and multiply by 16 (the number of beats measured in that time.) THIS is the BPM, which will be used to guide us in making the beat track.

Step two: Once you find ALL of the 4 measure times, find an average. The key here is to adjust the average so that when you’re done, you don’t have a string of hooks that sound like Toon Disney cover versions of the originals. In my sample version, I decided to use 9.500 because two of the songs were already slightly higher than that. Once you have a suitable average number, time compress/expand the songs so that they all are at that speed. (Mark 4 measures, precisely...adjust the target time to your average - then select the entire song and process.) Now, some of these songs will sound slow, some will sound fast, but when you mix, a lot of that won’t matter because you will be using very short hooks and provided you’re using a good beat track, that will help bridge the difference.

Step three is finding/making the right beat track. I use Groovemaker, a nifty little piece of software from Italy (don’t worry, it’s in English) that allows you to create your own tracks at whatever BPM setting you choose. Alternately, you can find a track somewhere else that is close to your average and adjusting it to the chosen speed. In my example, I came up with a track I liked and set the speed to 101.050 BPM or 9.500 seconds for 4 measures. (See, you DO need BPM.)

That’s really all of it. Yeah, some of it gets a bit complicated, higher math don’tcha know, but the rest is really simple. Just make sure that when you lay the tracks out, the downbeats of your songs match the downbeats of your beat track. Then the real artistry in you gets to shine and your boss won’t be able to resist giving you a raise... or something like that.

OK, check out the chart.

* Some songs are counted in “double” time to get them in the ballpark. All times are rounded to the nearest millisecond.

A couple of notes: 1. You can avoid the higher math (which you swore in high school that you’d never need) by purchasing Acid, another music software package that allows you to match speeds within the application. 2. When you time compress/expand your songs, you should really do the entire song because you might discover another part of the song will work better in your final mix. 3. If a song just sounds awful in the mix, try shredding it. (Don’t know about shredding? Watch this space.)

This is a skill you will need to practice! Don’t expect it to turn out exactly right the first time, and plan on putting in some long hours doing one of these bad boys until you get more adept at it.

♦