by Steve Cunningham

What do you have stored on the hard disks of your editing workstation? If you’re like me, you have the last several projects you worked on, and perhaps a few more that are still in progress. But is that really all that on those drives?

What about your computer’s operating system? What about the audio editing programs themselves — they’re on those hard disks too. So are all those free plug-ins you found on the Web, not to mention the ones you bought and paid for. And if those commercial plugs are copy protected, there are some little invisible files that tell your computer that it’s okay to fire up those plug-ins. You might even have a couple of months’ worth of email in there someplace.

Now, how much of the above can you afford to lose? How many hours or days would it take you to rebuild all that stuff on a new hard disk should yours decide to give up the ghost? You do have a backup, don’t you?

If you can’t answer “yes” to that question, then you’re already in deep doo-doo. After all, hard disks do go bad, sometimes spectacularly. Trust me, if you haven’t yet had a hard drive fail, you will.

A TALE OF WOE

Here’s a typical narrative, taken in the past week from one of the DAW-oriented mail lists to which I subscribe:

“The project was done. I did a test bounce on a rough mix. Stupidly, I forgot to remove some plug-ins I was beta testing. Right after the bounce the computer froze. On reboot the 60-gig hard disk which holds this project wouldn’t spin up! The drive is not stuck. Its servo is completely dead. I put it in the freezer to no avail. I tapped it with a plastic hammer to no avail. Since it makes absolutely no sound when AC is connected, I am quite sure the power supply inside the drive or servo is dead.

“For the first time since 1997, I lost data. For the first time in my life my drive died without giving me any sign. It didn’t give me any sign at all.”

Despite the number of horror stories I hear on the ‘Net and from my peers, I’m still amazed at the number of audio pros who are living on borrowed time, without a complete and regular backup regimen. But that’s okay... if you haven’t yet had a hard drive fail, you will. It bears repeating. I’m sure that you’re convinced that you need it; so let’s look at the current state of backup technology.

TAPE BACKUP

TAPE BACKUP

The oldest method of backing up uses a tape backup drive. These come in several flavors and formats, which are broken down into three groups: Travan and QIC, DAT and DDS (Digital Data Storage), and LTO (Linear Tape Open). Most tape backup systems store your data in a compressed format, usually at a ratio of 2:1. There are a large number of software programs that support tape backup, but they’re not all compatible across various versions of Windows, let alone Unix or MacOS.

With storage capacities from 20 to 40GB per cartridge, Travan records with a fixed recording head on an oversized cassette cartridge, and is considered an entry-level product class. If your PC came with a tape drive in one of the bays, it’s probably a Travan or QIC-format drive. The drives are available with SCSI, Atapi, or USB interfaces, and are priced in the $200 to $500 range depending on capacity and features.

DDS was created by Sony and HP in 1989, and uses DAT tape cartridges. Both DAT and DDS tape drives use helical scanning for recording, the same process used by a VCR. DDS tapes can hold from 8GB up to 40GB, and are considered a mid-range solution for backup. You can get a DDS drive for as little as $400, although drives with autoloaders that change tapes automatically can run you well over $2000.

LTO was designed for business use on server arrays, and can store up to 200 GB on a single cartridge. With prices starting around $2000 and increasing to $10,000, LTO is probably not a good solution for backing up editing workstations.

The main advantages of tape are that it can run unattended and overnight, and with the right software can backup several machines on a network in one operation. The tape cartridges themselves are inexpensive and easy to store, and tape cartridges are still available in most formats.

But there are several disadvantages to tape. Because tape is a linear medium and most formats store the directory at the beginning of the tape, restoring specific data can be a slow process. The tape mechanism must be cleaned regularly, and the tapes themselves need to be retired after a certain number of uses (DDS tapes are considered worn out after 100 full backups). Finally, if you’ve ever received an audio DAT from a client that wouldn’t play on your DAT machine, then you’ve experienced yet another disadvantage of using tape for backup.

OPTICAL BACKUP

The introduction of fast CD-R drives made the backup process much simpler and easier to accomplish. I did my own unofficial survey on backup amongst my peers, and the result was that most production types back up projects to CD-R or CD-RW.

CD-R drives are faster than ever, and cheaper than ever. You can find drives that will write a CD-R at 52x (given a 52x CD-R blank of course), which means that backing up 640MB of data takes as little as a minute and a half to write the data, plus 2-1/2 minutes for the lead-in and lead-out. That’s four minutes to backup over 70 minutes of audio, and that’s good.

You can still get SCSI CD-R drives if your workstation is set up for SCSI, but the best deals are for IDE drives. The last Plextor CD-R drive I bought cost me less than $80 shipped, and reads at 52x, writes at 52x, and re-writes (for CD-RW) at 24x speeds.

There’s lots of software available for making backups on CD-R and CD-RW, as described in “CD Software Roundup” in the November 2001 issue of RAP. Not much has changed since then, although most software companies have issued updates to maintain compatibility with the faster drives. On the PC I still like Nero Burning ROM from Ahead Software <www.ahead.de> for audio data, and Norton Ghost <www.symantec.com/sabu/ghost/ghost_personal/> for making a backup clone of the boot drive. On the Mac I like Roxio’s Toast Titanium <www.roxio.com> for backing up project data, and Carbon Copy Cloner <www.bombich.com> for making a clone of my OSX boot drive. All of these work well, and are regularly updated as newer, faster drives are introduced and as operating systems evolve.

It should be noted that while I do not recommend burning audio CDs at high speeds, burning data backups at high speed is just fine. In the case of data, should there be an error transferring data to or from the CD, the computer will simply re-request the data block until it gets a good one. This process can occur as often as necessary, and it will be invisible to you. The same can’t be said for audio CDs, where there isn’t time to re-request a block of data for reading or writing, and the error will likely cause an audible click. So burning audio fast = Bad, but burning data fast = Good.

The problem with using CD-R for backup is that one disk will only hold 640 MB, or in the case of 80 minute CD-Rs, 700 MB. I have folders containing promos that only ran 60 seconds in length, but contain 1.5 GB of data. The rest of that space is taken up by imported music and SFX tracks, VO takes and re-takes, regions that were processed with non-real-time effects and written separately to disk, and more. Backing up one of those folders takes multiple CDs, and keeping track of which parts are backed up where can be a real pain.

That’s why I love DVD for backup. DVD-R media will hold 4.7 GB of data, more than enough to back up a complete project or three. The media is more expensive, with good quality data grade disks priced around $3 each in quantity, but remember that they hold the equivalent of six CD-Rs. And as with CD-R drives, DVD-R drives are now dirt cheap — I picked up a Pioneer DVR-105 on the Web, the same drive that Apple puts in the latest Macs and calls the SuperDrive, for $168 shipped. That model will burn DVD-R at 4x real time, and CD-R at 16x real time.

Okay, so burning at 4X isn’t a big deal compared with 52X for CD-Rs. Nevertheless, it means that you can fill a DVD-R disc with 4.7 GB of backup data (and sleep a little better at night to boot) in less than two hours. I run mine at night, so I can take advantage of the better night’s sleep.

In addition, most CD burning software supports the latest DVD drives, including my two favorites Nero and Toast.

BACKING UP TO ANOTHER HARD DISK

Today’s hard disks are inexpensive — really inexpensive. If we’re talking about large EIDE hard disks (80 GB and up), you can find them priced at less than a dollar per gigabyte of storage. Big SCSI drives are still at least twice as expensive, but there are good deals to be found on the Web on SCSI closeouts.

Fact is, hard drives are now so inexpensive that they make fine backup devices! Conservatively, one gigabyte will store about an hour and a half of stereo audio at 16 bits and 44.1 kHz. A 120 GB hard drive (and today I’m seeing a Web deal on a Seagate at $80 plus shipping) will hold about seven days worth of stereo audio at 16/44.1. You read that right, SEVEN DAYS of storage, for less than we used to pay for a roll of 2-inch tape! At that price it makes sense to buy a few of them, and simply rotate ‘em. The only question that remains is how and where to connect them to your workstation.

INTERNAL VS. EXTERNAL

The easiest way to add a backup drive to your rig is to mount it inside the computer. All but the most ancient of PCs will have two or more IDE busses inside that are used to connect hard drives, along with CD-ROM and CD-R drives, to the motherboard. A single IDE buss can support two drives, which are designated master and slave on the buss.

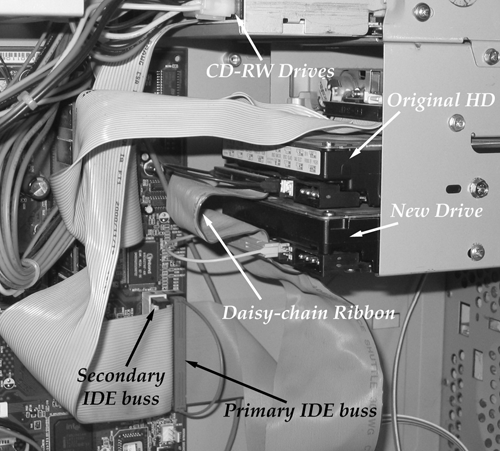

Most PCs I’ve checked come with a boot drive connected on the primary IDE buss, a CD-ROM drive connected to the secondary IDE buss, and two or three extra 4-wire power connectors for adding additional drives. It’s not hard to figure out how your PC is set up — just open the case and trace the ribbon cables from the existing devices back to the motherboard. The ribbon cables will probably have extra headers on them to allow additional drives to be daisy-chained on the IDE buss. And although we’re talking about PCs here, recent Macintosh computers also use IDE internally so everything applies on the Mac.

Assuming that there’s an empty drive bay or some other way to mount it, you can safely install another hard drive on the primary IDE buss and still another on the secondary buss. Keep in mind that the maximum speed of an IDE buss is dependent on the speed of the devices attached to it, so daisy-chaining a fast hard drive on the same IDE ribbon with a slow CD-ROM will slow the transfer speed of the hard drive substantially. This is not an important issue if you’re adding the drive specifically for backup purposes, but it will have an effect if you’re trying to record on it.

Looking at figure 1, you can see that I’ve installed a second drive in my PC on the same IDE buss as the original. My secondary IDE buss has two CD-RW drives attached, so with that done I’m all full-up. Note that I’ve removed the power connectors from both the hard drives to better show the ribbons. In my situation, I’d need to add a PCI-format IDE card to allow a third or fourth hard drive in the ol’ IBM. I still have a couple of unused 4-pin power connectors available so that’s no problem.

But adding internal drives also adds extra heat that builds up in the computer and can shorten its life. More heat is definitely a Bad Thing. So rather than adding more or bigger fans, I have chosen to use external drives for backup use.

EXTERNAL SOLUTIONS

It wasn’t always so, but today you can buy high-quality cases for external drives with several different interfaces. They come with power supplies and cables to hook ‘em up, and they’re ideal for mounting those cheap IDE hard drives. Just open the case, set the drive jumpers to Master (or to Cable Select, see the case instructions), plug the drive into the case and screw it down. Yer done.

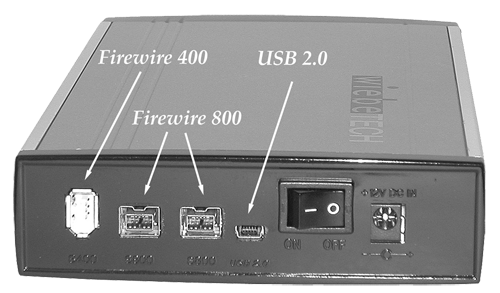

The two most popular interfaces for these external cases are USB and Firewire. The USB 1.0 interface specs out at 12MB/sec, and in reality runs substantially slower than that. For backup however, it’s fast enough and still outruns DVD-R. Besides, nearly every post-DOS PC has USB ports on it. Enclosures featuring USB 2.0 are now appearing, and those promise to be nearly as fast as an internal drive.

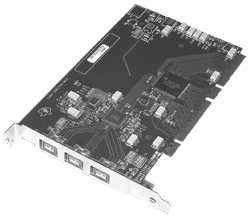

My personal favorite is Firewire. It’s now been around for a couple of years, and standard Firewire 400 is as fast as an internal drive. When picking a drive enclosure, make sure that it utilizes what’s called the Oxford 911 chipset in its IDE-to-Firewire interface for best performance. If you want to add Firewire to your existing PC, take a look at a PCI Firewire interface card (see figure 2). On the horizon is Firewire 800, which as you might expect is twice as fast as Firewire 400, although the connectors are different. And for those of us who can’t decide, there are cases with both Firewire and USB (see figure 3).

Finally, WiebeTech <www.wiebetech.com> has a clever solution for backing up on IDE drives called the Wiebe Dock (see figure 4). It’s a Firewire interface, sans case, that plugs into a bare IDE drive, making a smaller package and allowing you to store just the bare drive without an enclosure. As long as you only use one drive at a time, you don’t have to buy multiple cases to store them. It’s perfect for stacking up a mess ‘o bare backup drives for future reference — just pull ‘em off the shelf and plug ‘em in to the Dock. Clever.

WRAP

It’s clear to me that backing up on either DVD or hard drive is the way to go. The hardware is inexpensive and reliable, and the backup process is as simple and quick as it’s ever been.

There are just no excuses now, so finish reading this issue and go back up your stuff. Because if you haven’t yet had a hard drive fail, you will.

♦